This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

In Algeria, talking about sexuality means first confronting a void, one that is statistical, institutional, and symbolic. “Unlike other countries, we have no national survey on sexuality,” notes Dr. Khadidja Boussaïd, a sociologist at the Research Center for Applied Economics for Development (CREAD) at the University of Algiers. “The National Office of Statistics measures consumption, employment, housing… but not sexuality,” adds the researcher, who is also an associate member of the Centre for Gender Studies at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland.

This absence of data is not insignificant; it reflects a political and moral taboo that reduces sexuality to its reproductive function.

Sexuality: An almost uncharted scientific territory

To shed light on this gap, Dr. Boussaïd cites the few works that have attempted to break this silence.

In the 1980s, sociologist Fatma Oussedik and several other female researchers published Women and Fertility in Urban Areas, a pioneering work on contraception and family planning in which they already addressed issues of sexuality within a context of population control.

Two major figures then paved the way for reflection on “intimate sexuality” in the Maghreb, says Dr. Boussaïd. First, the Tunisian sociologist Abdelwahab Bouhdiba, who wrote Maghrebi Society and the Question of Sexuality (1984), which examines the links between religion, colonization, and the social body. Then, the Algerian anthropologist Malek Chebel, with The Spirit of the Seraglio (1988), which analyzes the taboos and gray areas of desire.

More recently, in 2023, psychiatrist Farid Kacha published That Thing…, in which he explores sexuality at the intersection of biology and psychology through clinical cases. He highlights the absence of sexology as a scientific discipline in Algeria. “The book’s title itself speaks volumes about the taboo surrounding the naming of sexuality,” notes Dr. Boussaïd.

Beyond this research, the scientific void remains. “There are no targeted surveys on sexuality in Algeria, only studies on reproductive health,” she continues. The MICS (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey) addresses fertility and contraception but ignores pleasure, desire, and intimacy.

This is also a political void: it defines the limits of what society is willing to acknowledge. Reproduction, yes. Pleasure, no.

This is also a political void: it defines the limits of what society is willing to acknowledge. Reproduction, yes. Pleasure, no.

A first survey on sexuality in Algeria is underway

In 2021, Khadidja Boussaïd decided to break the silence. With psychologist Boukraa Aïssa, she launched the first quantitative survey on sexuality in Algeria: “Sexuality and Gender Relations in Algeria.” Nearly 900 people took part in the survey—a groundbreaking project that is still ongoing, unfinished, and unpublished.

“Sociologically, we don’t speak of sexuality, but sexualities: a phenomenon that is simultaneously individual and social, cerebral and physical,” she explains. The preliminary results are already challenging long-held assumptions: 55% of participants believe that sexuality is not dependent on marriage, and 56% define it primarily as a source of pleasure. These trends reveal a silent shift in perceptions.

“Sexuality doesn’t begin with marriage; it begins with fantasy. As soon as we feel desire, we are sexually alive,” the sociologist insists. In a country where institutions do not yet study these issues, the survey shows that what is believed to be reality is often just a social fantasy: behind the silence, society is already living differently.

“We talk about women’s celibacy, never men’s,” Dr. Boussaïd observes. Yet the two are evolving in parallel. Since 1966, the age of first marriage has steadily increased: from 18 to nearly 30 for women and from 23 to 33-35 for men. This delay does not reflect a rejection of relationships or sexuality, but rather a transformation of timelines and expectations. “Women have shifted their social—and therefore biological—clocks.” They are studying longer, working more, and postponing marriage, without giving up on love or desire.

In a country where institutions do not yet study these issues, the survey shows that what is believed to be reality is often just a social fantasy: behind the silence, society is already living differently.

Men, for their part, are facing a crisis in the “provider” model. “They want to continue providing housing, income, and stability, but it’s becoming increasingly difficult.”

Couples are therefore reinventing their lives outside of institutional frameworks, often in secret, sometimes in fear, always in a fragile balance between freedom and constraint.

Living as a couple outside of marriage

Assia, 36, welcomes me into her small, tidy apartment on a quiet street in central Algiers. She has been in a stable relationship with her partner for three years without being married.

“At first, it was very stressful,” she says. “I was afraid of getting pregnant, of being judged, and that everything would fall apart if someone found out about us. I thought that only marriage could protect me.”

Over time, fear has given way to a sense of balance. The couple operates with a discreet code: a message is all it takes to signal a family visit and avoid running into each other. “It’s our way of keeping the peace with the neighbors. We’ve learned to live between the lines.”

Today, Assia speaks of choice. “My relationship suits me because it respects my freedom. I can work late, travel, make my own decisions. It’s not a rejection of marriage, but a refusal to be defined by it. My only concern is the desire for motherhood: I don’t want to get married to have a child and then get divorced.”

“My relationship suits me because it respects my freedom. I can work late, travel, make my own decisions. It’s not a rejection of marriage, but a refusal to be defined by it.”

Her testimony, which she says is shared by several of her friends, describes a generation that doesn’t reject relationships or sexuality but redefines love in a different way.

In a society where everything is codified—modesty (heshma), honor (sharaf), shame (‘ayb)—desire becomes a form of intimate rebellion. And the intimate, Dr. Boussaïd reminds us, is always political. “Sexuality is shaped by images, words, sounds. Cinema, music, religious sermons, and advertising mold our imagination.”

Loving despite multiple stigmas

Nadia joins us for coffee, and with her, another fragment of history is added to Assia’s narrative.

Long, immaculate black hair, vibrant blue-turquoise-yellow clothes, orthopedic shoes. Leaning on her crutch as if it were a scepter, Nadia enters with an energy that shatters the silence, and her radiant laughter precedes her words. Active on social media, she reads and comments on testimonials with a sharp humor that has become her form of resistance. “If men have sex outside of marriage, according to the comments, it’s because they can’t afford to get married, even though married men are also looking elsewhere. And it’s always the women’s fault: not pious, not reserved. We become the ‘loose ones,’ the ‘bad girls.’”

She laments that people can’t simply acknowledge their emotional and sexual needs. Then her voice softens. “With my disability, I’m doubly stigmatized. When a man wants to take things further, his mother refuses. I’ve realized that for many, being in a relationship depends less on who I am than on what they see.” At 39, Nadia prefers virtual exchanges. “Simpler, sometimes endearing, and above all, less humiliating.”

The line between desire and violence is thin. “Very often, people only want to talk to me about sex, even if they don’t know me,” she says. “Some people take advantage of my disability to pressure me into sending photos or saying things I don’t want to say.”

A few minutes later, Assia calls Inès, 27, their friend who also has a disability. Inès hesitates on the phone, then confides, “Since I graduated, I hardly ever go out anymore. I depend on my parents. The internet is my window to the world. I look for people to talk to, sometimes more. But often, it ends badly. Twice I’ve been blackmailed after intimate exchanges.”

She pauses, then continues. “The first time, I thought it was my fault. The second time, I realized it was because I’m a woman and ‘no one would want me in real life.’”

Since then, Inès hides her disability on dating sites. “As soon as I mention the wheelchair, most people block me.” Inès laughs softly. “What surprises me is that on Facebook, I see many disabled men posting marriage ads. They’re looking for a serious, pious woman for a life within the bounds of Islamic law… and everyone congratulates them, encourages them. But when a woman dares to say she want to love or be loved, she’s immediately judged. As if, for us, expressing a desire is already a lack of modesty.”

For researcher Khadidja Boussaïd, these stories are by no means marginal. “People with disabilities, especially women, are among the most excluded from the public sphere. But the digitization of the world and social media offer them symbolic access to this space: they can finally exist, exchange ideas, desire—even if the virtual world remains permeated by the same power dynamics.”

According to the sociologist, social media has redefined life as a couple: it circumvents family taboos while revealing, in the digital space, new power dynamics between genders.

The digitalization of intimacy: A refuge and a battlefield

According to the sociologist, social media has redefined life as a couple: it circumvents family taboos while revealing, in the digital space, new power dynamics between genders.

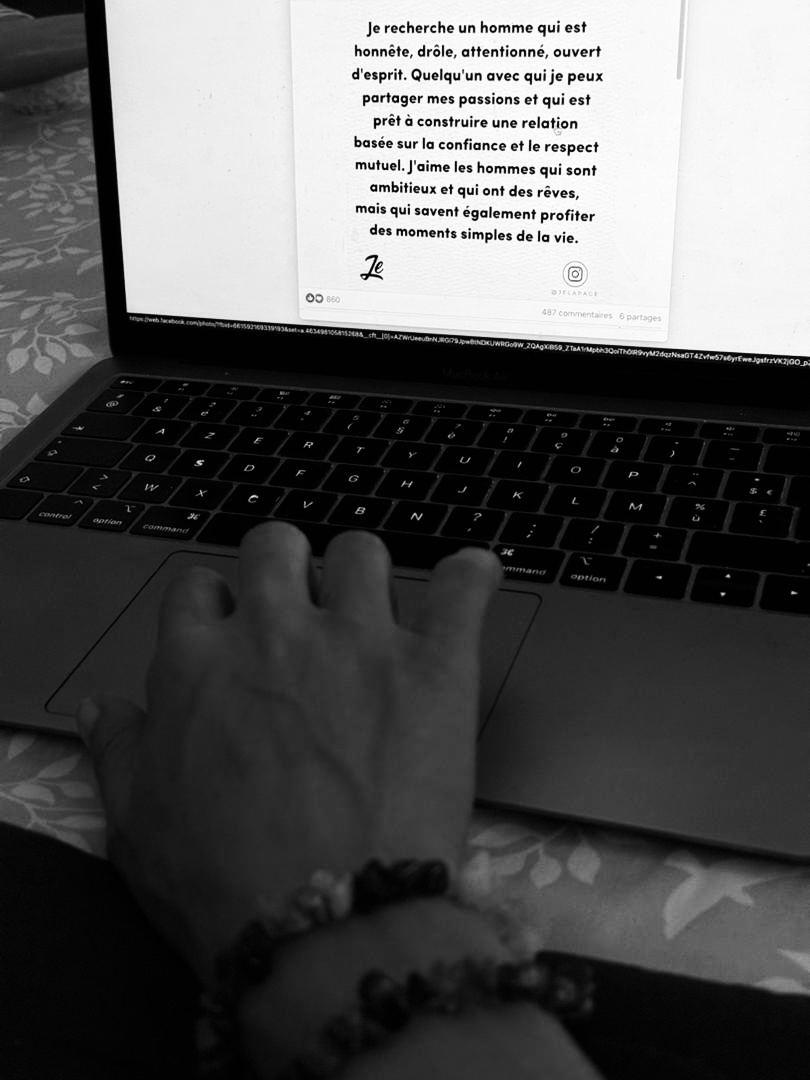

Encounters now take place on Instagram, Snapchat, or Facebook, often under pseudonyms, in a clandestine world where seduction, flirting, and emotional connection are reinvented—but so are forms of control.

The internet offers unprecedented freedom of expression, especially for women marginalized by age, social status, or disability. But this freedom remains fragile: the virtual world reproduces and amplifies social and gender hierarchies.

In Algeria, digital technology hasn’t eliminated taboos; it has simply displaced them. Behind their avatars, women continue to negotiate their right to pleasure, caught between moral surveillance, a desire for autonomy, and a need for recognition. The virtual world is not a refuge, but an intimate battlefield.

Voices of women with disabilities: Between self-esteem and violence

In her office in Algiers, Souad*, president of an association for people with disabilities, recalls the moment in 2023 when she too decided to break the taboo by working on the sexuality of women with disabilities. “We talk about functional autonomy, never about emotional or sexual autonomy. Yet these women have the same needs, the same desires, the same rights as everyone else.”

The activities carried out as part of this project revealed two deep wounds. The first has to do with self-esteem: many describe their love stories as trials of validation. “He accepted my disability…” they often say with a mixture of gratitude and resignation. Their desire remains haunted by a painful question: who would agree to love a body deemed imperfect? Love then becomes a favor, not a right.

The second wound is that of sexual violence and blackmail. Some women were abused by partners who invoked “help” or “compassion.” Others have been emotionally blackmailed, their physical or social vulnerability used as a weapon. “These are invisible forms of violence. These women don’t dare speak out, for fear of losing what little freedom they have,” confides Halima*, a participant who herself has a disability, whom we met at the project’s launch workshop in 2023.

These harrowing accounts show that the right to pleasure remains a battleground. Between fear of judgment, the lack of inclusive sex education, and difficulties accessing gynecological care, their bodies remain monitored—sometimes violated.

Souad also notes the frequency of the expression “unnatural,” often uttered by parents who refuse to imagine that their daughters could love or want to get married. For her, the current struggle is clear: to defend the right to remain a woman, despite disability—a woman with needs, emotions, and desires.

For her, the current struggle is clear: to defend the right to remain a woman, despite disability—a woman with needs, emotions, and desires.

The work of Khadidja Boussaïd and the testimonies collected by Souad, a disability rights activist, show that female desire in Algeria—the right to an emotional and sexual life—does not disappear under the norm. It adapts and resists.

From the personal to the political, one idea recurs: sexuality must be recognized as a fundamental right, not a fault.

Inès recounts that at weddings, some women are told, “Inshallah, you'll be next,” as if making a promise for the future. To her, in a wheelchair, they simply say, “May God protect you for your parents.”

Until society learns to talk about desire—and even love—without shame, freedom will remain incomplete, and its margins will continue to define its boundaries.

*Pseudonyms

This article was carried out with the support of the Tunis Office of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.