This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

What Is Consent? is the first book in this series, and it will be followed by other books on corruption, stray animals, recycling, and biodiversity. Why did you choose consent as a starting point here?

Society in Tunisia is undergoing profound transformations, but we don’t pay attention to their impact on children. I’ve noticed a huge gap in awareness about sexual violence against children—it’s still a taboo topic, not only in Tunisia but even in Switzerland and France, where it’s difficult to talk about incest or domestic violence.

My first idea was to teach children to say “no.” Consent is a sensitive topic, so we addressed it indirectly, through issues like harassment, sexual assault, and domestic violence, in a simplified, age-appropriate way.

Each book in this series contains environmental, feminist, or anti-colonial messages. I was told I had to start with a light topic. But this book about consent is the foundation of the entire project: I cannot help parents or educators instill concepts of diversity, respect for others, and conservation of the environment and animals without first teaching children self-respect.

The story is based on questions asked by the two young protagonists: How do I know that I want to withdraw my consent? and What should I do if someone invades my privacy? What I want to ask is, how did you go about writing this book?

It took me three years to write it. I collaborated with Dr. Khadija Bouzghaia Bagbag, a child psychiatrist, to ensure age-appropriate content. During our first meeting, she explained to me that the best way to address complex issues is to let children ask their own questions, and then build dialogue. This was the core methodology of the project.

I cannot help parents or educators instill concepts of diversity, respect for others, and conservation of the environment and animals without first teaching children self-respect.

I also watched many documentaries about sexual violence and consent and borrowed about 30 books from the library, from which I extracted approximately 70% of the questions children might ask. As I moved forward with the work, new needs emerged—the book went beyond the story itself. We added a section listing the relevant authorities’ phone numbers and a practical guide for parents, as well as an interactive section allowing children to draw scenarios in which their consent was not respected.

Because it was important for you to present a comprehensive book that’s accessible to a wide readership, it has been published in three languages: colloquial Tunisian Arabic, English, and French. This is in addition to the Braille, sign language, and audio versions. Are there any differences in content across these?

No, the content is the same in all the book’s versions. But the audio version is somewhat clearer due to the absence of images. The book is primarily aimed at a Tunisian audience, but it’s suitable for any child from a non-Western culture. The girl with a unibrow and curly hair doesn’t only represent Tunisian girls.

I also wanted to immortalize elements of Tunisian culture that children today don’t recognize anymore, like the Berber tattoos that adorned grandmothers’ faces.

It’s an entirely Tunisian project. I wanted to make a difference in the field of children’s literature in Tunisia. When I was young, I didn’t see any beautiful books for Tunisian children. Which is logical: making them is expensive, it requires a lot of effort, and it doesn’t generate profit. In the youth library in Lausanne, where I grew up, the books available to me were so pretty, colorful, hardback, and varied. When I visited Tunisia, I found only small, low-quality books, bland and unattractive. So I wanted to change this.

On a technical level, publishing this book in Tunisia was a major achievement in balancing quality and price. But it’s also going to be exported abroad. I’m delighted to see Arab names on children’s bookshelves, which are usually dominated by non-Arab publishing houses and authors.

The Mom, Dad, Can We Talk About series is an ambitious project. You also proposed the idea of distributing the book to associations for free. Did you receive external financial support?

No, I didn’t receive any funding. I ate rice and was penniless for months, slept on the floor without a bed. I started the project four years ago and finished my studies in February 2025. My first real paycheck was in May. Before that, I’d been juggling exhausting student jobs and various internships.

I never wanted anyone to work with me for free. The opposite—I made sure they were paid above average. I worked night and day to achieve this. I was offered funding, but it was tied up in geopolitical affairs I didn’t want to be associated with.

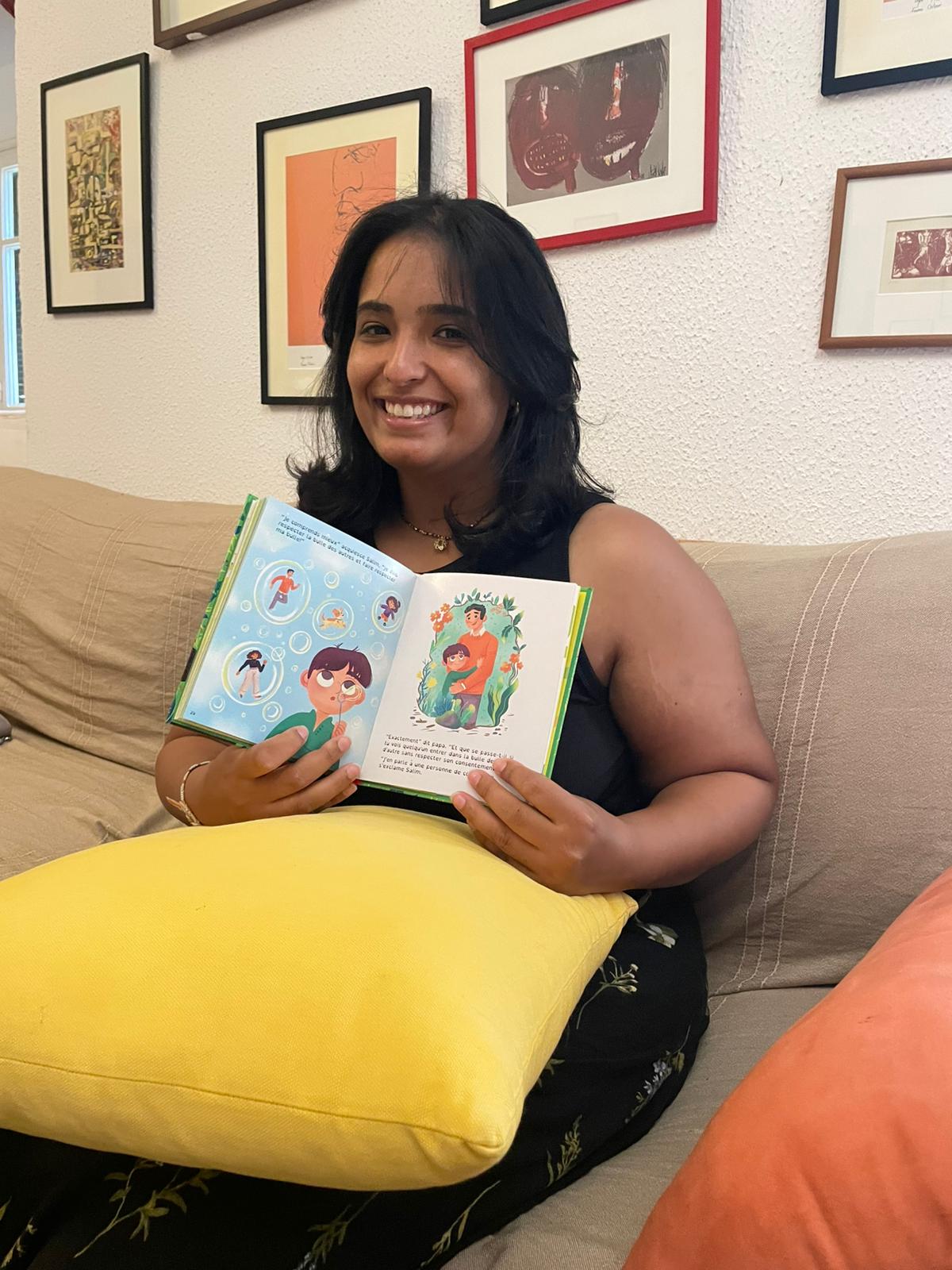

The 26-year-old writer lives between Switzerland and Tunisia. She was still a master’s student in politics and public administration at the University of Lausanne when she launched the Mom, Dad, Can We Talk About project.

So far, I’ve financed the project with my own money. I hope it will eventually fund itself with the revenue it makes. Financially, I’m working at a loss, but I see it as a “gift to my country.” Until I can effect deeper change through my studies and career, I can’t stand idly by.

What was the reaction after the first copies sold?

Honestly, I didn’t expect this success. In Tunisia, books are more about entertainment, it’s more that than in-depth educational books that focus on values. When I launched it at the Tunis International Book Fair, I said to myself, If we sell three copies a day for four days, I’ll be happy. We sold 55 copies!

What was even more wonderful were the reactions people had. A mother bought the book to read with her daughter. When they got to the interactive part, the girl drew herself in the bathroom. Her mother asked her what that meant, and the little girl confided that she was uncomfortable with the way the woman who works in the bathroom had touched her. The girl was able to express in words an uncomfortable situation she hadn’t dared talk about before. To me, this alone proves the book has achieved its goal. I imagine it will later enable this child to recognize dangerous situations before they become serious problems.