This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic) VO

Four women are bustling around behind a steel counter. On the shelves are crates of fragrant Annurca apples, a specialty of the region that is fully locally produced. Deftly, with great focus, and using small, sharp knives, the women core, chop, and throw the washed apples into large pots. Then they add cinnamon and brown sugar for the ultimate result: one of the most popular jams of the Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena (Gluttony of the Lorena House). This catering, gastronomical, and jam business was started 10 years ago by the social cooperative EVA, and it also houses a small bakery—but its real success lies elsewhere.

All the women who work at the Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena, and those who work at Eva.Lab and La Buvette di EVA—the two other companies established by the EVA cooperative—are women who have been victims of violence. Thanks to this work, they can (re)discover their own autonomy after having lived through long periods of suffering. They are all (or have all been) supported by the women operating the five anti-violence centers that EVA manages in Campania.

These women are given a new job, a regular, not-underground work contract, and a monthly salary to get back on their feet and give them back their dignity. They learn to manage their own money and open personal bank accounts for the first time (in Italy, only 37% of women have personal accounts), fully emerging from the situation of dependence that had cemented their “belonging” to men who claimed to love them but who soon revealed their abusive tendencies.

They are offered support and accompanied through the difficult process of getting free from a violent partner, through the trials that follow abuse and mistreatment complaints, through lengthy separation or divorce proceedings, or even through child custody struggles. Some of these women stayed in one of the three shelters that EVA manages before finally being able to rent their own houses. With the help of EVA psychologists and educators, many of them have also been able to rebuild their relationships with their sons and daughters who were traumatized by years of domestic violence.

Each of these women reached a turning point in their lives: the moment in which they understood that by continuing to endure their situations in silence—as social conventions dictate, as a (good) wife must—they were not only putting their own lives in danger but those of their children especially.

“I didn’t want to take my children away from their father,” most of them say. And it is precisely through their children that men control and dominate their wives, locking them into housework and the care work they do for their families, tasks that seem only to fall on mothers, on fimmine (females, in local dialect). More often than not, men force their wives to quit their jobs when they have one: “I’ll take care of you,” they promise. “No one can say that I can’t provide for my wife.”

EVA, a feminist cooperative business

“When we started the cooperative in 1999 and opened the first feminist anti-violence center in our region, there was no other structure of the kind in the whole province of Caserta,” recalls Lella Palladino, a sociologist and one of the founders of the cooperative of which she was also the president. Today, EVA has 20 members and about forty women workers.

In Italy, the first anti-violence centers managed by women’s associations were set up in the early 1990’s in large cities like Milan, Bologna, Palermo, Rome, and Genoa. Their strength lay—and still lays—in the relationships they foster between women, the “operators” and “survivors,” and in the political interpretation of male violence against women. From a feminist standpoint, this violence cannot be reduced to isolated acts that make some women’s lives more difficult. It’s more than that: it’s a systemic social phenomenon that touches the lives of all women, in one way or another, and that is fueled and legitimized by patriarchal culture and the stereotypical roles attributed to men and women throughout history.

“Another important distinction to make is that we are in Campania, one of the regions of Italy where women are the worst off,” the sociologist adds.

According to data published in November 2022 by the Italian Court of Auditors, less than one in three women (29.1%) in the region has a paid job, while the national average employment rate is 49.4% (around one in two women). Women are also the ones to whom are attributed 75% of the total hours of unpaid work in the field of care-giving and the education of children (against a national average of 67%) according to estimates of the International Labour Organization (ILO). The ILO has identified this specific “family welfare” as the cause of women’s very low employment rate in Campania.

“We continue to not read this data in relation to the data we have on violence—starting with economic violence, one of the most widespread forms of the control and abuse of women,” Palladino emphasizes. She gives a few examples: “Forbidding women to work outside the home, or forcing them to have their salaries credited to a personal chequing account in the husband’s name. Then it becomes the husband’s job to allocate small sums of money for the women to get groceries—the women will always have to beg, will have to be continuously humiliated. And as soon as they dare to stand up to their spouses, the insults and belittlement begin: “I’m the one who sustains you, you do what I say!” Over time, men tighten the chain around their wives’ necks more and more, and the violence only increases.”

This explains why the founders of the EVA cooperative quickly came to understand that even if women had taken a course in an anti-violence center, if they didn’t have a job, they were always at risk of falling back into a relationship of economic dependence, or even of returning to the same violent partner.

“Unemployment levels here are high for everyone. Not just women, but young people too, even men. The alternative is to work under the table, without a contract, with no rights. And on top of everything else, there is the Camorra: the organized crime organization that controls the whole territory,” Palladino explains. “So we had to really invent it, this work we offer to women escaping situations of violence!”

And thus the first two professional integration workshops for women victims of violence were born: Le Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena and Eva.Lab. Both based—not by coincidence—in Casal di Principe.

Casal di Principe: promoting legality in Camorra country

The streets are narrow, deserted, almost always one-way, only partly bordered by bumpy, tiled sidewalks. The houses have large sheet metal doors that block the view and close off access routes to the interior courtyards. In the past, carts used to pass through them, then tractors. Today, cars are the main vehicles in sight. There are often no exterior windows on the ground floor: only from the mezzanines, which have narrow terraces, is it possible to see the street, the courtyards of neighboring houses, the expanse of the roofs of Casal di Principe. The village, which has a population of about 20,000, gave its name to the Casalesi clan, one of the most powerful organizations of the Camorra.

The buildings that house Le Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena and Eva.Lab also share this kind of architecture.

The two buildings are properties that were confiscated from the Schiavone family, a member of the Casalesi clan depicted in Gomorrah (1), the nonfiction book of investigative journalism by Roberto Saviano published by Einaudi in 2006. The book became a bestseller and was translated into dozens of languages before being adapted for the screen: the movie was directed by Matteo Garrone in 2008. It also inspired the television series of the same name and was created and broadcast by Sky between 2014 and 2021 (on Canal+ in France). The show won several awards. Since the release of his book, Saviano has been living under police protection.

“Follow the money,” Giovanni Falcone used to say. Falcone was an anti-mafia judge who developed this innovative investigative method to fight organized crime. He was the instigator of what went down in history as the Palermo Maxi Trial against Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian mafia organization that assassinated him on May 23, 1992, along with his wife and the police officers escorting them. It was he and the Antimafia Pool he was part of who turned the seizure and confiscation of the assets of the representatives of organized crime into systematic procedure. This was their attempt of hitting the Mafia’s financial capital and halting the reconstitution of the clans.

There are hundreds of apartments, buildings, shops, warehouses, sometimes entire businesses, land, and farms all over Italy, North to South, without exception, that belonged to the Mafia. Since the creation of the National Agency for the Administration and Destination of Assets Seized and Confiscated from Organized Crime in 2010, there has been new momentum in getting these properties reused, regulated by Law 109/1996.

“Law 109 has made it possible to request that confiscated goods also be used for social initiatives, so as to lead communities onto a lawful path where the Mafia, the Camorra, and the 'Ndrangheta previously reigned,” explains Daniela Santarpia, President of the EVA cooperative. “This is exactly what we did when we were assigned the first building, which became Casa Lorena, an anti-violence center with a shelter. That was also where we set up the gastronomic workshop Le Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena, thanks to a project that was initially supported by the Campania Region.”

“Today, Le Ghiottonerie is a sustainable business,” Santarpia proudly declares. “We produce the Marmellata delle Regine (Jam of the Queens), a jam made from oranges picked in the gardens of the Royal Palace of Caserta. It is sold as a co-brand in the shop of this historic residence. We also offer catering for a variety of institutions and occasions. We make chocolate and pistachio spreads from the milk of our local buffaloes and, more recently, tarallini and other savory biscuits—they sell very well!”

“In addition to Casa Lorena, we also have a second confiscated building, also in Casal di Principe. We restructured it to set up a crèche not only intended for the children of the women supported by EVA but for local families too, as there are very few of these kinds of establishments in our region,” Santarpia explains. According to calculations by OpenPolis, Campania is the region with the least coverage in Italy when it comes to crèches with a mere 11,747 places for about 150,000 children.

“This is also where the Punto Luce (Source of Light) was set up: a leisure center for children and teenagers aged 7 to 17. It was created in collaboration with Save the Children,” she adds. “But above all, it is here that we started the ethical fashion workshop Eva.Lab in 2020. It’s our second professional integration laboratory for women escaping situations of violence.”

Eva.Lab: escaping violence through a silky embrace

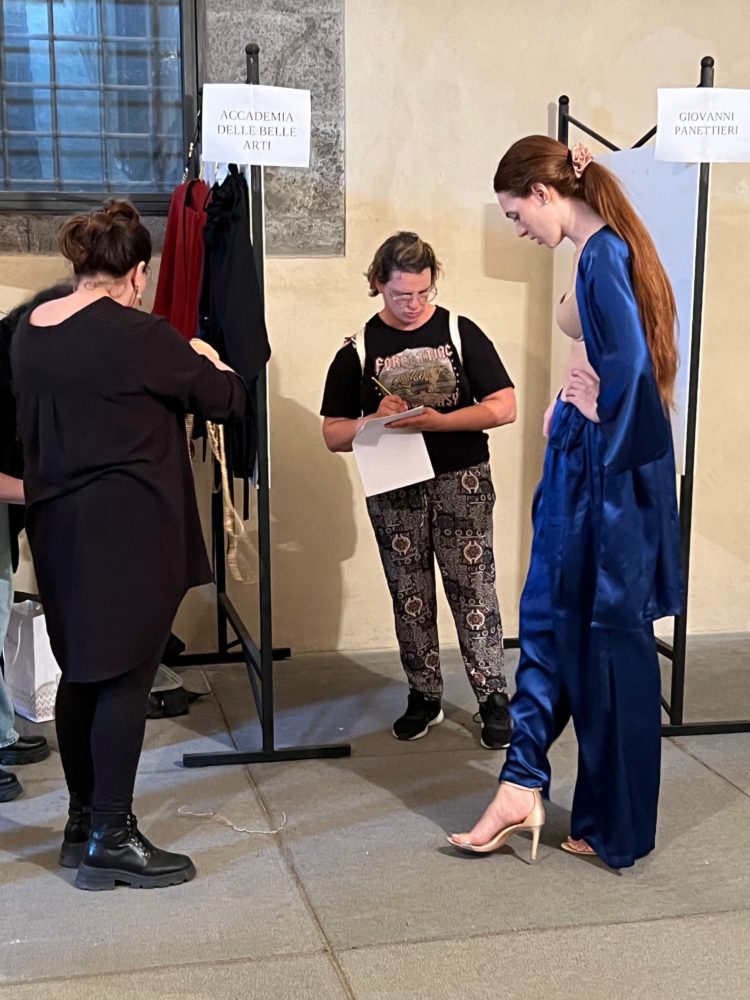

To admire Eva.Lab in all its glory, we went to Naples, to the Maschio Angioino, on June 10. The castle, with its mighty dark towers, one of the symbols of the metropolis at the foot of Vesuvius, hosts “Napoli Fashion Design,” a showcase event for Neapolitan creativity in clothing and interior design. It is now in its tenth edition. Eva.Lab was invited to the runway for the first time—the emotion of the seamstresses who created the ten outfits the models will show off on the catwalk was palpable!

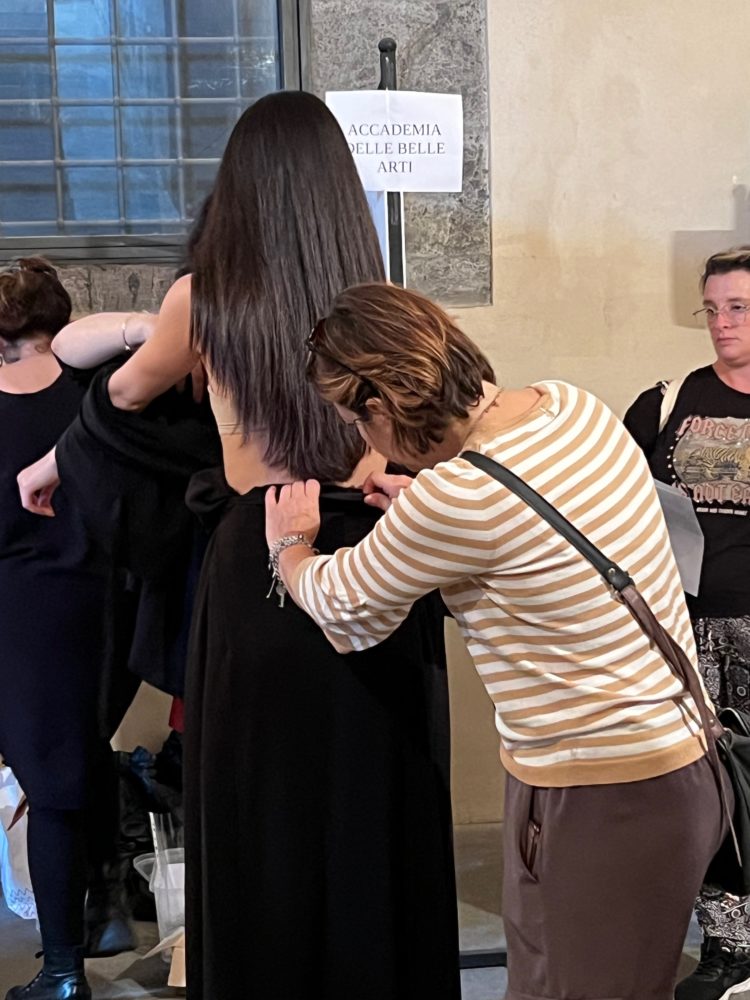

We were also at the fitting: the dressing rooms were set up in a room inside the castle. The models were walking around, tall and beautiful, the seamstresses adjusting palazzo pants with wide slits, shirts with puffy sleeves, small tops, and ruffled dresses to the models’ bodies. We could hear the music that the models would walk out to, and they were trying out the poses and gestures that would best show off each design. The seamstresses were concentrated and serious, but there was an undeniable sparkle in their eyes.

“This adventure began in 2020 with a project financed by the Campania Region in collaboration with San Leucio Textiles, the consortium of textile factories that carries down the legacy of the silks designed at the end of the 18th century in San Leucio, in the suburbs of Caserta, by Ferdinand IV of Bourbon, an enlightened ruler,” Daniela D'Addio, who runs the workshop, told us. “We were supposed to make kimonos and silk turbans, but then the pandemic hit, and we went into confinement. So we started by producing washable fabric masks that we distributed for free to anti-violence centers across Italy. This was a time when masks were very difficult to find.”

Another important partner working with Eva.Lab is the Naples Academy of Fine Arts (ABANa), specifically the fashion design course with professors Maddalena Marciano and Angelina Terzo. They supervise the workshop while Carmela Amodeo designs the models. It is thanks to their advice that the last details of the fashion show are finalized: the choice of accessories, makeup, and hair.

“The garments on show this evening were made from silks provided free of charge to Eva.Lab by Gucci as part of Gucci Up, a project that aims to give new life to excess production,” D'Addio explained. “It’s proof that the business model we set up for Eva.Lab actually works: it is built on virtuous partnerships and gives value to the land, focusing on the circular economy, reuse, and environmental sustainability. This adds a plus to the intrinsic social value of Eva.Lab, considering the concrete support it offers women escaping situations of violence.”

“It is obviously a different kind of workshop,” D'Addio emphasized. “Here, women’s time—and therefore their work patterns—is respected. Their difficulties are taken into account. It is a priority to give them the space to rebuild their lives. But we also value their talent, skills they’ve forgotten, like embroidery.” She showed us the red arabesques skillfully drawn with needle and thread on a pink silk belt.

Meanwhile, night had fallen: a gigantic moon stood out against the Naples sky, and the Maschio Angioino courtyard lit up with a thousand lights. The clothes made in the Casal di Principe workshop were shown off one after the other: tunics, high-waisted skirts, shirts that swell in the sea breeze. Whenever a model climbed up the irregular steps of the elevated catwalk, the seamstresses held their breath.

They were relieved to hear the applause greeting the final walk down the runway of all of Eva.Lab’s clothes, but the seamstresses did not get on the runway themselves to receive the applause. They preferred to remain behind the scenes. Maybe the time will come for them, too, to stand proudly alongside their creations. But for now, they are letting the clothes bear witness to their revival.

La buvette di EVA: a rebirth

It is not easy for those who have suffered violence to tell their story. To tell is not only to relive the trauma but to find oneself inexorably crushed in the role of victim. “Feminism teaches us that it’s not the details of the violence that count. The stories are all alike because male violence against women is a social, collective, widespread fact,” Palladino asserts.

“However, we’ve realized over time that violence has been represented as an immutable fate, one without alternatives. Fortunately, in our experience, this has not been the case. Women can effectively free themselves from violence: they rediscover their strength and are proud of the progress they have made, and their success can serve as an example and inspiration for other women and young girls,” the sociologist continues.

These reflections further pushed the EVA cooperative in its intention to change the narrative around violence: last year, it embarked on a new adventure and took over the management of the cafeteria of the Mercadante Theater in Naples, a historic site that overlooks Piazza del Municipio, right in front of the Maschio Angioino. This was how La buvette di EVA was born. It opens every day at noon and evenings during shows.

“We put up large signs all over the theater foyer indicating that all the women who work at La buvette di EVA are women who have escaped violence and are regaining their autonomy,” Palladino tells us. “We’ve explained that everything we serve is prepared by Le Ghiottonerie di Casa Lorena—that is, by women who have also escaped violence. And we’ve exhibited one of the most beautiful kimonos made by Eva.Lab… In short, they’re here, among us, smiling, proud, professional. A far cry from victims.”

Today, their voices are also starting to be heard.

Tiziana Ermini is one of the women who work at La Buvette di EVA. Tall, blonde, wearing a black dress with one cold shoulder and draped in a white stole made by Eva.Lab, she spoke about her rebirth on July 3 at the International Women’s House in Rome. All around her were famous Italian singers like Fiorella Mannoia, Caterina Caselli, and Noemi, actresses Anna Foglietta, Vittoria Puccini, and Vanessa Scalera, and the actor Marco Bonini. They gathered to celebrate the creation of Una Nessuna Centomila, the new Italian foundation dedicated to preventing and combating violence against women.

The audience gathered in the Magnolia Courtyard was moved by the description of the psychological violence Tiziana suffered for years: “the most difficult violence to recognize, that which leaves the deepest marks, that which made my son tell me, ‘mom, you’ve lost your smile’.” They were then indignant at the battles that Tiziana is still waging in court—one judge said to her, “I don’t believe a single word you’ve said.”

But it’s upon hearing Tiziana’s words describing how working at La Buvette di EVA changed her life, “Today, my husband can’t hurt me anymore because I’m much stronger than him,” that the audience broke out in encouraging and liberating applause.