This post is also available in: Français (French)

Clermont-Ferrand is the capital of the Puy-de-Dôme department in France. The 25-Gisèle Halimi Center is located on Rue Lucie et Raymond Aubrac, a street named after a French couple who resisted the German occupation during the Second World War. Halimi is another key figure in French history—her surname also embodies struggle, albeit one of a different nature. The Franco-Tunisian lawyer and activist is known for the Aix-en-Provence rape trial, her activism in favor of legalized abortion in France, and, more generally, her fight for women’s emancipation.

Halimi’s smiling face radiates on the building’s façade. The center consists of a space of 743 m² spread over two floors, the whole of it dedicated to women. Three associations are housed there, free of charge, by the municipality of Clermont-Ferrand: Family Planning, the Centre d'information sur les droits des femmes et des familles (CIDFF—Women's and Family Rights Information Center), and A.V.E.C-France Victimes. Various partners also provide occasional support, such as the Bar Association and the Family Allowance Fund (CAF). Every resident can, among other things, obtain a medical consultation in gynecology with or without social security coverage, get informed about her rights, receive free support from a psychologist for those who are victims of violence, or rest freely in the break room.

One place to help address different issues

The creation of this center in December 2023 is part of a more global anti-discrimination policy that has been strengthened in recent years in this town of nearly 150,000 inhabitants, headed by the socialist Olivier Bianchi. Following his election in 2014, the mayor set up an equal rights mission which was represented at first by a municipal agent. Today there are four of these agents, and the 2025 budget provides for the hiring of two more. Some of them are physically present at the center, as the coordination of its activities is an integral part of the work carried out by this delegation.

The project to come up with this space followed the Grenelle des violences conjugales, the series of roundtables that brought together associations and political leaders and was organized across the country between September and November 2019, during President Emmanuel Macron’s first term in office. “The prefect of the Puy-de-Dôme department organized a reverse conference with women who had gone through domestic violence and who came to talk about their difficulties. Many said they knew about the 3919*, but then in Clermont-Ferrand they were given the numbers of four different associations. Who to call? For what reasons? It was confusing,” sums up Marie Costenoble, coordinator of 25-Gisèle Halimi, part of the equal rights mission.

As soon as they walk through the door of the center, which is locked by an intercom, all women are greeted by a single counter. The hostess at the entrance is in charge of directing women who already have an appointment. Others would be interviewed to best identify their needs. Costenoble is an advocate of unconditional listening. “We want to be a place of listening and care. If an interview has to last three hours, it will last three hours.”

Premises adapted to support victims of domestic violence

On the second floor, Nathalie Quesnel, a social worker with A.V.E.C-France Victimes, takes us on a tour of the premises: a children’s play area close to the psychologist’s office, isolated behind transparent glass, a waiting room equipped with a computer so women can carry out administrative procedures in peace, and an area with secure lockers to deposit documents or personal belongings. Quesnel assists women who want to leave their marital home. The reception area is designed to enable these women to plan their departure in good conditions, as opposed to those who leave in a hurry and risk having to go back home. In addition to having “superbly adapted premises,” Quesnel sees several advantages to being in a center that caters to a broad public. “The women who come to 25-Gisèle Halimi do not all initially come for problems of violence. This allows us to identify new victims who don’t always recognize themselves as such.” The social worker points out that there is no typical profile. “We receive women from all socio-professional categories, of all ages, mothers or not.”

“We want to be a place of listening and care. If an interview has to last three hours, it will last three hours.”

Access to healthcare for all

Downstairs again, we arrive at the health center. The decline in the number of practicing gynecologists convinced the municipality to add access to healthcare for all, in addition to a reception point for women victims of violence. The needs in this area are real. In December 2024, of the 967 women who came to the center, 610 benefited from a family planning consultation (gynecological and pregnancy follow-up, contraception, medical abortion, etc.). Since its opening, the number of visits to the 25-Gisèle Halimi has steadily risen. In the first months of 2024, around 600 women were counted.

Although the vast majority of these women are victims of violence, the services offered by the center are aimed to meet the needs of all women. This is part of what sets it apart from the Maisons des femmes that now exist in several French cities, including Clermont-Ferrand since November 2024, a stone’s throw from the 25-Gisèle Halimi.

The two structures will work closely together. While the Maison des femmes is designed to be a care unit, the 25-Gisèle Halimi is more than just a health center. It is also a resource center with exhibitions exploring the theme of women’s rights, and even conferences.

Recharge your batteries

On this February morning, a sports workshop is taking place for the third week running. The facilitator suggests activities according to what the participants want. The three women who answered the call on this Monday morning are working out to music, doing muscle-strengthening exercises. “Each woman does what she can, at her own pace. It’s a two-hour window, but the physical activity part doesn’t usually last that long. It’s also a time to talk about everyday life,” explains the sports educator, Baptiste Boulet. Boulet also hopes to organize outdoor outings in the future. Anne (1) is a little out of breath; she says she has “lost a lot of muscle mass” and feels the need to do sports to cope with medical problems. Manon (2) encourages her—“You’re doing great!” This young woman signed up for the sports workshop after having attended the sophrology workshop. “I was looking to rediscover myself, to take care of myself. I’d forgotten myself, thinking of others first, always. This has let me reconnect with myself,” she says. It was the 3919 that directed Manon to the 25-Gisèle Halimi. A “secret garden,” in her words, where she also received psychological help for several months. “I wouldn’t have been able to consult a paid psychologist because I’m currently out of work. It helped a lot,” she shares.

As a professional, Quesnel sees great value in these workshops. “They allow us to offer more things after women’s appointments. It helps them not stay in their victim status. They can meet different people and regain their self-confidence to reach out to others.”

The only one of its kind in France, the 25-Gisèle Halimi is an inspiring place. The equal rights mission has been contacted by several French cities that would like to replicate the Clermont-Ferrand model.

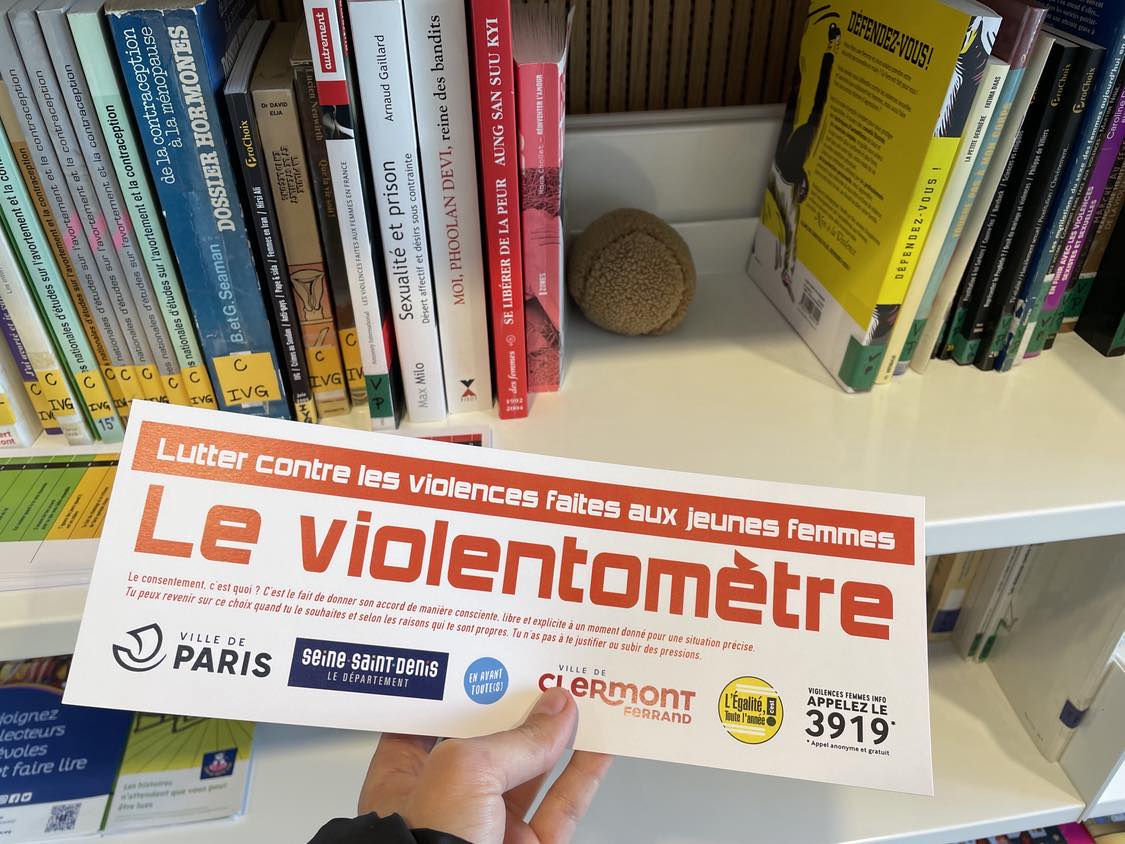

In the break room, there is a feminist library with free access. On the edges of the shelves are various prevention and awareness-raising flyers: contraception is men’s business too, 20 million people don’t have access to abortion in Europe. “The idea is for this place to have visible documentation for women. They come to see an exhibition or attend a conference, and they get all this information too. Women who aren't ready to talk about their problems yet can just come and get their bearings,” Costenoble points out.

The only one of its kind in France, the 25-Gisèle Halimi is an inspiring place. The equal rights mission has been contacted by several French cities that would like to replicate the Clermont-Ferrand model.

Participants’ names have been changed to protect their anonymity.

The 3919 is the French helpline and referral number for listening to and guiding women victims of violence.