This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

There can be no democracy without a media ecosystem in which women play a full part—not only in producing and shaping news, but also in representation that respects their rights and diversity.

It’s with this notion in mind that the ESEC (1), the Economic, Social, and Environmental Council—in partnership with Equipop, Reporters Without Borders, Prenons la Une! and La Fronde—organized a day of discussion and reflection on women and the media on Wednesday, February 25. The event was announced as follows: “A large-scale conservative offensive is unfolding on a global level, targeting women and minorities in particular. With this kind of backlash, what role does the media play in the functioning of democracy?”

Two key moments were intended to address this critically important question: a morning discussion between news professionals hosted by Equipop (2) and an afternoon plenary session in the form of a radio program hosted by Julia Foïs of France Culture and Benoît Bouscarel, a former Radio France journalist and founder of the community media outlet L'Onde Porteuse (3). The program was broadcast before March 8 by 68 community radio stations across France.

The particularly effective radio format consisted of three segments: Words are not neutral, To be a woman journalist: At what cost?, and The media landscape in a context of backlash (4).

Resist

Her long brown hair frames the determination that animates her face: Salomé Saqué is not yet 30 but exudes an impressive lucidity served by an incisive tone. A journalist with Blast and the author of several books, including Résister (Resist) (5), she got the post-meridian debates off to a flying start: “Civil society is a place of resistance to strengthen and protect democracy… all those who are calling for the destruction of places where we can debate and gather want to destroy our democracies,” the journalist asserted, urging her audience to resist, each at their own level, this democratic disintegration in a “dangerous international context.”

“A large-scale conservative offensive is unfolding on a global level, targeting women and minorities in particular. With this kind of backlash, what role does the media play in the functioning of democracy?”

“Our rights are never guaranteed,” Saqué added. “We cannot remain neutral in the face of discriminatory and dehumanizing discourse.” One need only look to the United States to realize that reliable and independent news is a thing of the past. Steve Bannon, Trump’s mentor, advocates a technique consisting of “flooding the zone with shit.” Relying on Musk and his control of social media, Trump is imposing a Newspeak that excludes all references to minorities and women’s rights, which are clearly under threat: contraception is being called into question, the abolition of the right to abortion has been demanded and is now enacted in certain states such as Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

“Objectivity is the subjectivity of the dominant”

Independent journalism, which ethically respects the Charter of Munich, is an essential safeguard against authoritarian excesses. This is why it is targeted by conservative and far-right forces that accuse it of militancy and subjectivity in an effort to delegitimize it. “Even media outlets that are far from revolutionary, such as ‘Le Monde,’ are subject to the same accusations,” Saqué noted, quoting feminist journalist Alice Coffin: “Objectivity is the subjectivity of the dominant.” Journalistic objectivity is an illusion: only points of view based on sourced facts can sustain a healthy media landscape. In France, this landscape is undermined by the extreme concentration of media in the hands of billionaires such as Bolloré, whose ultraconservative line is detrimental to diversity of opinion. These monopolies and the rise of the far-right media are distorting the democratic process by promoting a discourse based on identity and security. Salomé Saqué reminds us that “in France, it would only take 18 months to wipe out all checks and balances.”

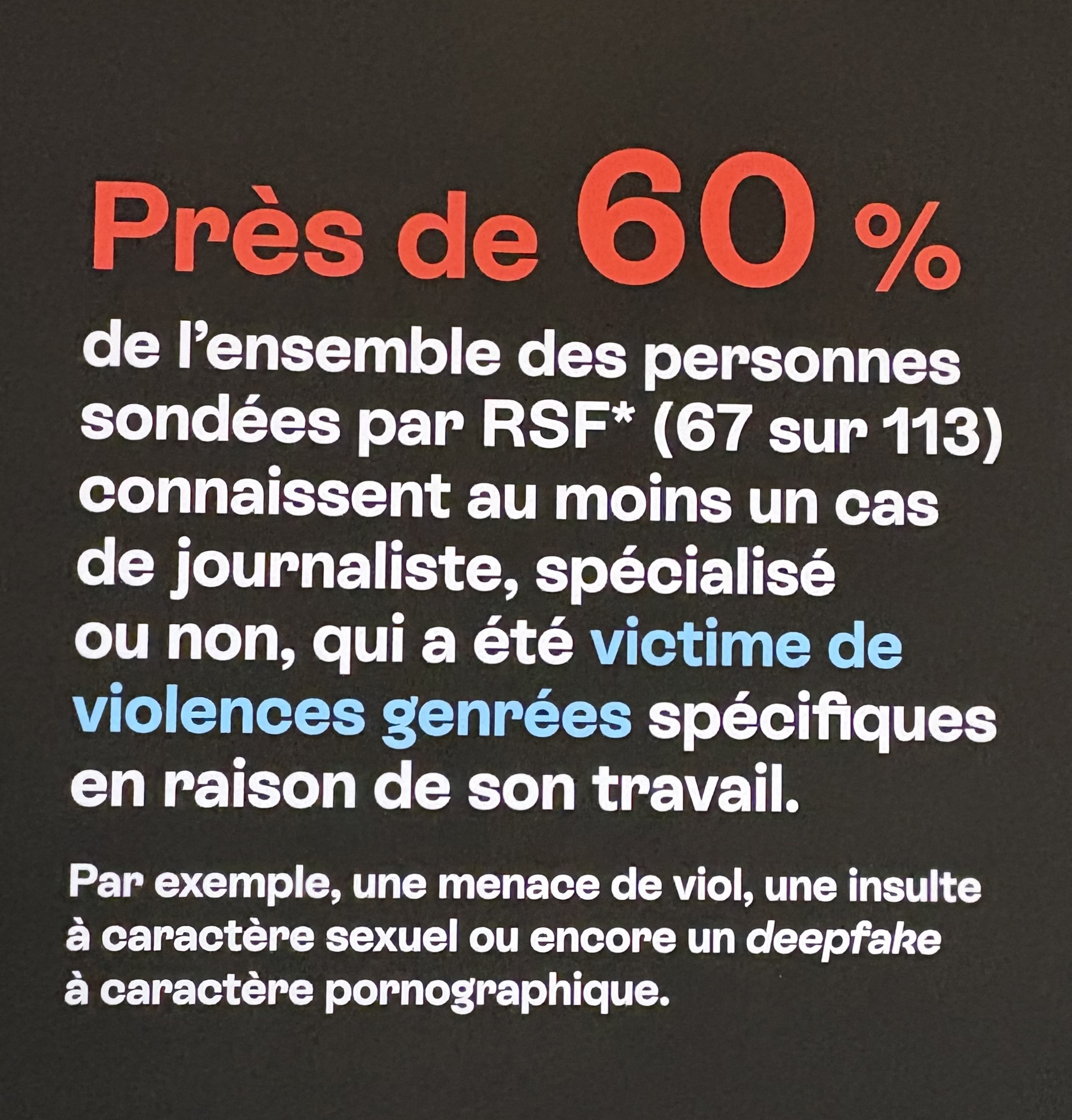

Female journalists have it tough. They are 27 times more likely to be harassed than men, and 73% of them have experienced harassment.

Female journalists harassed

In such a toxic media environment, female journalists have it tough. They are 27 times more likely to be harassed than men, and 73% of them have experienced harassment, explained the author of Resist, who received “thousands of hate messages in just a few days” after the publication of her book. Saqué was the target of an abject form of online attack: pornographic deepfakes—edited photos, created by AI, depicting her naked.

“It was a shocking experience. I almost gave everything up at that moment,” she commented, interrupted by a burst of applause from the floor in solidarity. The young woman also touched on another theme particularly close to her heart: the joy that comes from human connection. “I can overcome obstacles thanks to the moments of joy that come from working together. It’s this joy that keeps me sane…”

The words to say, the words we can no longer silence, the words we no longer want to hear

It was imbued with this energy that the presentations and debates continued for the rest of the afternoon, punctuated by the contributions from professional female journalists who, through their personal accounts and analyses, suggested critical tools and concrete proposals to change the situation. Journalists Johanna Luyssen and Souad Benhaddad began with a healthy semantic reappraisal. From now on, we need to call a spade a spade, choosing the term “sexual assault” over “abuse” or “sexual touching,” which are far too vague, even from a legal point of view. We must no longer silence the word “feminicide”—a word which is still not enshrined in French criminal law. “In France,” Benhaddad said indignantly, “the press considered this word to be too ideological until the numbers forced us to adopt it. Only the numbers made it no longer taboo. Let’s be wary of the words we don’t use.”

As Johanna Luyssen points out, “Along the way, editorial staff realized that sexual and gender-based violence was a real issue.” An important step, considering that Hélène Rytmann, Althusser's wife, was rarely mentioned in the press after being strangled by her husband in 1980.

Knowing how to name things also means being able to use the right grammatical forms, adopting the active voice rather than the passive, which always focuses on women in their status as victims and diminishes men’s responsibility. “We need to talk about male violence,” explained Spanish feminist journalist Pilar Lopez Diaz, a doctor of information science. “Men are the active subjects of violence, the ones who rape, attack… we don’t talk enough about men as perpetrators of violence.”

Let’s keep up the fight

Despite all the progress we’ve witnessed over the past 15 years, with the fourth wave of feminism, the explosion of the DSK and PPDA affairs, the publishing of magazines like Causette, the actions like that of the association “Prenons la une,” and, of course, the French MeToo… journalists who cover sexual and gender-based violence are still ghettoized in their media. These are the same media in which slimy sexist remarks and hands on buttocks have yet to be eradicated: comments like “You have a nice ass,” “a nice pair of tits” are still said to female journalists in their workplace, as in the testimonies reported by Emmanuelle Dancourt, president of the #MeTooMédias collective, and Nora Hamadi. For the latter, a producer at France Culture, everyday sexism is part of a media ecosystem that has trouble with diversity. “Where I work France Culture, editor’s note), I’m the only non-white person, the only one who didn’t go to Sciences-Po or a journalism school,” explained the young woman with an atypical background. Coming from the suburbs, this former sociology teacher boasts a complex and courageous trajectory that has led her to work, for her weekly program “Douce France,” on territories and populations that are invisibilized. This invisibilization poses, just as it does for women, “a problem of representation and therefore of democracy.”

And yet, good media practices are slowly but surely making their way into editorial departments, as Laëtitia Greffié, editor-in-chief of Ouest-France, explains. “The age pyramid has made it possible to feminize the editorial team and have journalists who cover gender issues.” An equality network has been set up within Ouest-France, and tools such as anti-sexist writing guidelines are being adopted on a daily basis to address gender issues and sexual violence.

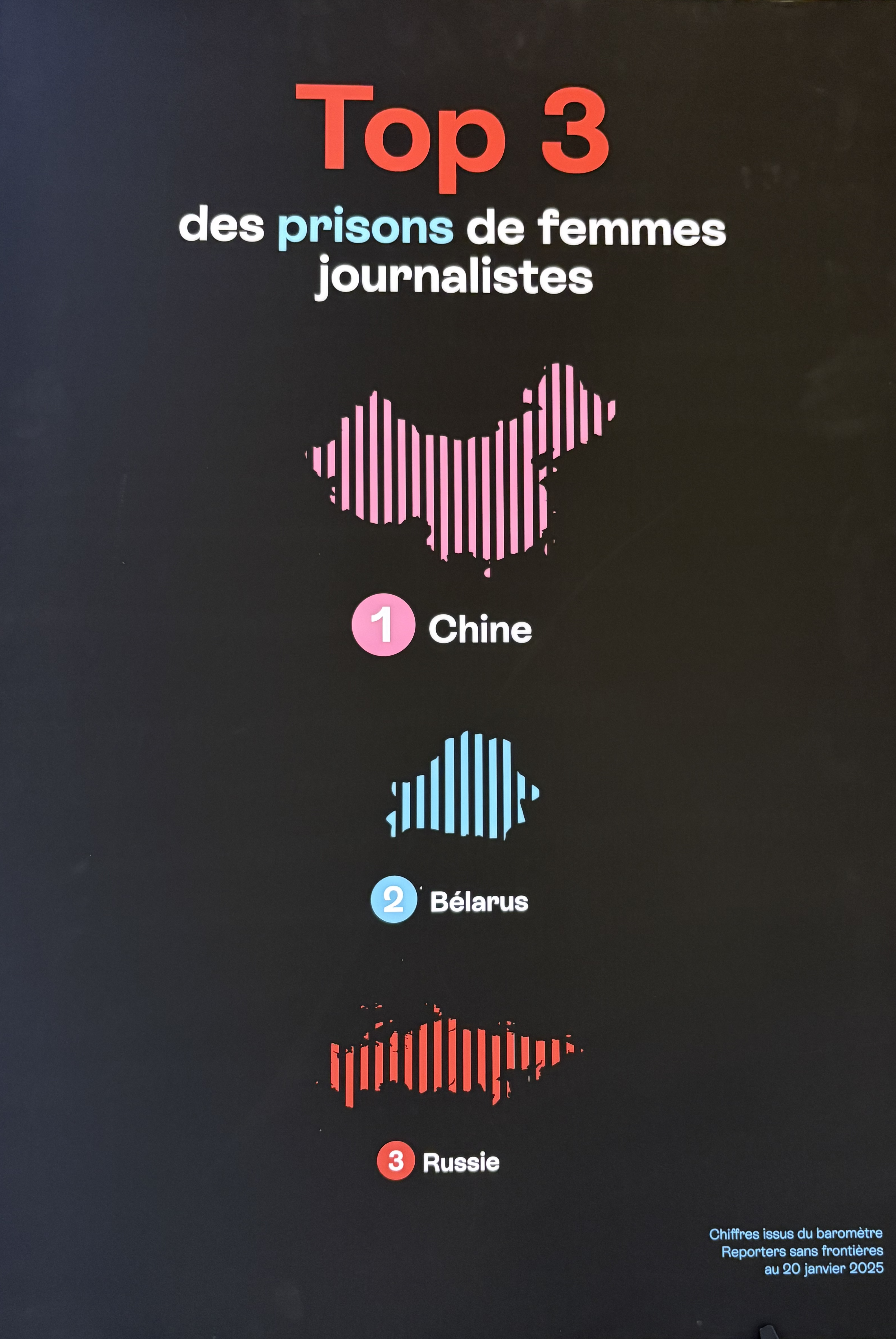

The day ended with the opening of the Reporters Without Borders exhibition “Journalism in the era of #MeToo.” Gigantic photos set up in the majestic hall of the Palais d'Iéna reminded us that women journalists and human rights defenders all over the world, like Iran’s Narges Mohammadi, Afghanistan’s Mursal Sayas, China’s Huang Xueqin, Argentina’s Mariano Iglesias, or Liberia’s investigative journalist Bettie Johnson Mbayo—to name but a few—are discriminated against, threatened, imprisoned, while they risk their own lives to produce news and denounce the regimes that oppress them.

Gathered around them on the evening of February 25, we felt stronger together.

To hear all the rich and lively exchanges of this radio show, you can click on this link.

Notes:

The ESEC is the third constitutional assembly of the Republic. It is a key component of French democracy, advising the government and Parliament and representing the democratic expression of civil society.

org and the Jean Jaurès Editions Foundation have produced a thoughtful study on “Women's Rights: Combating the Backlash.”

Workshop-style writing, integration projects, etc. L'onde porteuse is an inclusive media outlet that has enabled 150 people to return to work.

“Les mots ne sont pas neutres” (with Souad Belhaddad, Pilar Lopez Diaz, Johanna Luyssen), “Etre une femme journaliste, à quel prix” (with Laëtitia Greffié, Aurélia Sevestre, Emmanuelle Dancourt, Nora Hamadi), and finally “Le paysage médiatique dans un contexte de backlash” (with Anne Bocandé, Alexis Lévrier, Dominique Pradalié, Marlène Coulomb-Gully, Lucie Daniel).

Salomé Saqué, Résister, Payot 2024