This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

Interview by Olfa Belhassine

When did your academic interest in Tunisian female directors begin? I’m thinking of your previous work analyzing the careers of filmmakers, both male and female, in the Tunisian diaspora.

The question of the diaspora was at the heart of my thesis, which had both a historical and an aesthetic angle, on French filmmakers of North African descent. I defended my thesis in 2015, and it led to the publication of the book Le cinéma d’Abdellatif Kechiche : prémisses et devenir (The Cinema of Abdellatif Kechiche: Premises and Becoming) (Riveneuve, 2016). In the thesis, I discuss how the character of the immigrant was portrayed in French cinema in the 1970s. Later it was the immigrants themselves, particularly second-generation immigrants, who took the camera and filmed characters from emigrant families.

In 2016 and the years that followed, I shifted my interest in these issues to the cinema of the Maghreb and the Middle East. More specifically, I became interested in female filmmakers from these territories living in France and participated in conferences and seminars on this topic. One of my interventions, presented in 2017, was titled “Female figures of revolt in Tunisian fiction films (2000-2020).” Speaking of cinema and gender, I lengthily observed female cinematographers on set in Tunisia. This field work was supervised by the HESCALE research group, which is specialized in the film industry and brings together French and Tunisian researchers.

Do you notice any differences between how women are represented by first-generation Tunisian female directors, such as Selma Baccar, Kalthoum Bornaz, Moufida Tlatli… and the way they are represented by filmmakers who garnered success after the revolution, such as Leyla Bouzid and Kaouther Ben Hania, who live in the diaspora?

The major difference between the women we call the first-generation filmmakers and the next generation of these filmmakers lies in how they address the question of emancipation and the grasping of power. Women are no longer represented as mere victims as they were in Moufida Tlatli’s The Silences of the Palace (1994), for instance, in which Alia, Khadija’s daughter, tries to free herself from a sad destiny but ultimately ends up suffering the same fate as her mother, with the repeated abortions she undergoes.

Conversely, these characters now take their destiny into their own hands, particularly in Kaouther Ben Hania’s Beauty and the Dogs (2017) and in the final scene of Raja Amari’s Buried Secrets (2009). The women portrayed in these films are fighters, up against an oppressive power, as we can also see in Leyla Bouzid’s As I Open My Eyes (2015), in which Bouzid’s heroine, the young, 18-year-old Farah, coming of age in the time of dictatorship, does not allow herself to be intimidated by police harassment and proves to be a very active character.

What are the threads of interactivity that female directors living in France weave with post-revolutionary Tunisia?

They very often keep one foot in Tunisia—a very strong link with their country of origin. I am thinking here of Raja Amari, Kaouther Ben Hania, and Leyla Bouzid. So far, their films have dealt with the Tunisian question; we do notice a sort of transference in their films. Take for instance Amari’s Foreign Body (2016), in which the character of an illegal migrant lives between Tunisia and France. Also Bouzid’s latest film A Tale of Love and Desire (2021), which also addresses emigration and in which the protagonist’s entire story—a young student from Tunisia—takes place in Paris. I put forward the following hypothesis: by anchoring themselves more and more in French territory, these directors in the diaspora are also attempting to address the French question. All while remaining very attached to their native country—they continue to deal with Tunisian characters and to be interested in societal developments, especially as relates to women.

As women of the diaspora, what perspectives does their status offer to female directors of the new generation who stand out at international festivals?

There are two levels to these perspectives. First, these directors—compared to those who continue to live in Tunisia—have the opportunity to keep a certain distance between them and the stories they manage to tell. They are able to view what is happening in their country of origin through a different, freer lens, one not bound by self-censorship. They are able to address taboo issues differently.

This status also protects them from the wrath of social criticism. I am thinking of Raja Amari’s Red Satin, which caused great controversy in Tunisia when it was released in 2002. The other positive that these directors can benefit from is the opportunities for production and distribution of their films. They can more easily access French funding and aid from the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image (CNC), which in turn promotes the distribution of their films in France.

Are these directors interested in the life and political dynamics of Tunisia post-2011 revolution?

Yes, as we can particularly see in Leyla Bouzid’s first film, As I Open My Eyes, which takes an opposite stance regarding what happened in January 2011. She does not speak directly about the revolution but rather the months preceding this event, the climate of fear and dissidence which at the time reigned over the country. In the film Buried Secrets (2009) by Raja Amari, the director describes the oppression that weighs so heavily on women that the political metaphor imposes itself on the narrative.

Erige Sehiri has had a unique journey, one that unfurled in the opposite direction: born in France, she returned to Tunisia to film. Her way of filming female agricultural workers in Under the Fig Trees (2022) is particularly interesting. Under the guise of mere anecdote, she uses the love affairs of these young agricultural workers to show the strength of character of the women she portrays. Despite their apparent fragility, they are in reality powerful women. The political allusion in this story is clear: the filmmaker refers, among other things, to the tragedies of the death trucks, the makeshift means of transportation in the Tunisian countryside due to which many rural women have died.

Ben Hania subtly evokes the way the revolution of a country influences the “personal revolution.”

In Beauty and the Dogs by Kaouther Ben Hania, the director evokes police impunity. The great strength of this film is its demonstration of the fact that the departure of the dictator did nothing to contribute to the change of a repressive system. Ben Hania had to wait for the revolution to film Challatt Tunes.

Because it was almost impossible before then to obtain authorization to make documentaries. Clearly, one of the major changes after January 14, 2011 is that directors became able to tackle the documentary genre, closer to reality than fiction—hence the difficulty of its being allowed under an authoritarian regime.

Finally, we cannot fail to mention Kaouther Ben Hania’s latest film, Four Daughters (2023). Her point of departure once again being a news story, the filmmaker tells the story of Olfa and her four daughters, but there is also a question, implicitly presented, of the different social and political stages the country has gone through since the revolution. Ben Hania subtly evokes the way the revolution of a country influences the “personal revolution,” in this case, Olfa’s own.

From being of prime importance in cinema, how do the female directors of the 2010s-2020s film women? Are they lensed through the “female gaze” (1), the feminine gaze that Iris Brey speaks of, which presents women as subjects and strives to insert their experiences at the heart of the narrative?

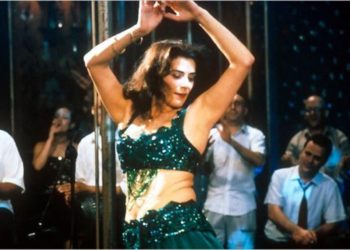

This particular gaze you speak of began with Raja Amari, even before the revolution. Amari is positioned at a pivotal point between the two generations of Tunisian female directors. With her, we experienced a real change in Tunisian cinema. In her first feature film Red Satin (2002), we leave the medina, where most Tunisian films used to take place, for the modern city of Tunis. The way women are represented is also different. And the portrayal of oriental dance, which is at the center of this film, seems totally different from what it would have been under the male gaze—the masculine lens which until now still totally takes over Egyptian films, for example. Oriental dance, which before then had been fully fetishized, here becomes an instrument of power for this widow, a mother who leaves the dullness of her life for an existence that is, quite frankly, subversive—“disturbing public order.”

In the opening scene of Leyla Bouzid’s As I Open My Eyes, in which a young girl intuitively discovers desire, we sense, in the way the scene is filmed, that there’s a woman behind the camera: we feel closer to the skin; the camera, which brushes against the body, does not exploit it.

In her latest film, A Tale of Love and Desire, I find Bouzid’s way of using the power of literature to translate desire very beautiful. She gives it a poetic coating. The filmmaker thus opts for a fairly unique representation of desire, literally suggested by the words of the work that are superimposed on the phantasmagoria of the film’s main male character, Ahmed, in reference to the platonic and ethereal love that Qays (the character of Majnun) has for Layla (2).