This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

The cover image was generated by artificial intelligence.

A sense of responsibility that ignores the real culprits

As an African woman, I have often felt an implicit pressure in ecofeminist discourse. As if we were responsible for bearing the burden of the ecological transition, when we are among the first victims of an extractivist system we did not create. Why are we being asked to give up a minimum of comfort while the multinationals of the Global North continue their predation with complete impunity?

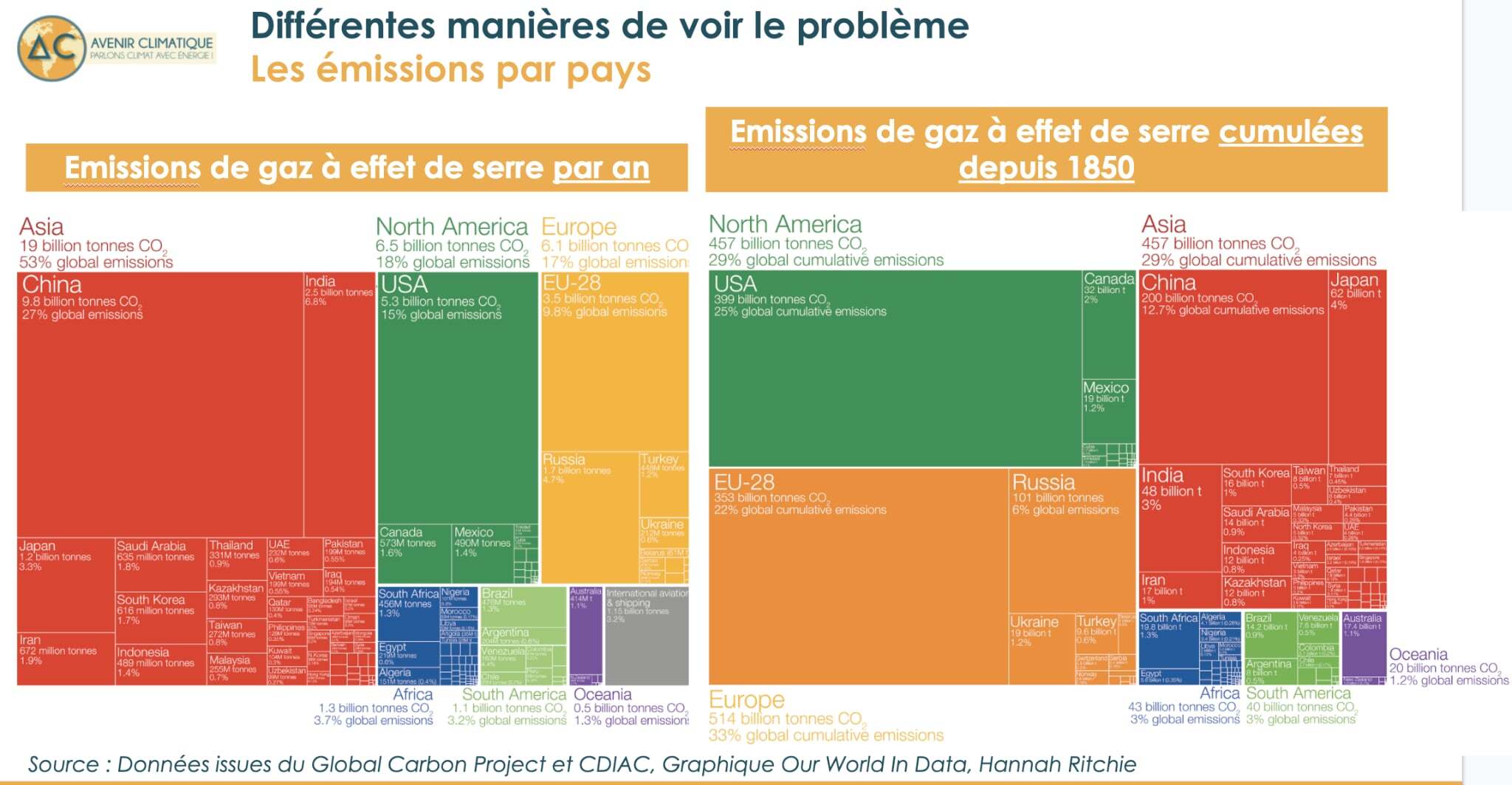

Africa emits just 3.8% of the world’s CO2 (Global Carbon Atlas, 2023), yet it is already bearing the full brunt of the consequences of climate change: droughts, land grabbing, forced migrations. Meanwhile, 100 multinationals are responsible for 71% of greenhouse gas emissions since 1988 (Carbon Majors Database, CDP, 2017). We know who is destroying the planet. We know who is paying the price. So why is it still the women of the Global South who have to answer for it?

Absurd, out-of-touch solutions

Yet many organizations in the Global North present us with “green” alternatives that take no account of our realities.

In 2021, in Algiers, I attended an ecology workshop for sub-Saharan migrant women, organized by an international NGO. The main topic was washable diapers. Not only does this approach still exclusively target women, but it completely ignores the living conditions of those for whom it is intended: violence, poverty, lack of access to water, and the absence of infrastructure.

Yes, around 12% of Algeria’s waste consists of disposable diapers (AND). But who should take responsibility for this pollution? Should women, already crushed by mental burdens and unpaid domestic labor, still have to compensate for an economic model they didn’t choose? Why not ban northern multinationals from producing this waste in the first place? Who really benefits from this cycle of production and over-consumption?

The trap of green capitalism and institutional feminism

Far from being a step forward, the integration of ecofeminism into the policies of international NGOs operating in Algeria has stripped their demands of any political weight. Doing nothing to challenge capitalism and neo-colonialism, these policies shift responsibility onto individuals—women in particular.

Green microfinance programs, presented as opportunities for “women’s eco-entrepreneurship,” are a blatant example of this: indeed, 90% of the women involved in these programs remain vulnerable in precarious sectors such as informal agriculture and crafts, among others.

We know who is destroying the planet. We know who is paying the price. So why is it still the women of the Global South who have to answer for it?

In Algeria, even though women constitute most of the student body in university programs specializing in green professions, they are gradually disappearing from the job market and positions of responsibility: they only form 11% of these, according to the Ministry of Labor. Why is women’s expertise still made invisible? Why do so-called “inclusive” policies simply move women around, without ever giving them decision-making power? And why aren't these issues a priority in a country where feminism remains more taboo than environmental struggles?

North-South: a persistent colonial divide

The climate crisis hits unequally: 75% of the climate-displaced live in low-income countries (UNHCR), while the wealthy nations, the main culprits, are closing their borders. By 2050, 1.2 billion people could be displaced (Oxfam France), 80% of them women and girls (UNHCR) exposed to violence and insecurity. Meanwhile, multinationals exploit the resources of the Global South with impunity.

Rather than penalizing major polluters, agreements such as the Paris Agreement remain non-binding. Armed conflicts are recognized as grounds for asylum, but desertification is not, even though millions of people are already being forced to flee.

The history of extractivism shows how the destruction of nature and the exploitation of people in the Global South are linked. In the Niger Delta, Shell and ExxonMobil contaminated land and rivers, depriving Ogoni women of their livelihoods (Amnesty International). Today, these same companies benefit from carbon-offset mechanisms, which allow them to continue polluting while appropriating land in the Global South.

Women—particularly indigenous and rural women—are on the front lines of environmental defense. In 2023, over 40% of murdered defenders were women (Front Line Defenders). How can we justify the silence surrounding their struggle? Why is the ecofeminism that reaches us not interested in these struggles? Are we too far removed from our anti-capitalist ecofeminist sisters, or has institutional co-optation limited our spaces for exchange?

The example of Algeria

Though it is the most polluting country in North Africa, Algeria is still a very low emitter of CO2 on a global scale. Yet it bears the full brunt of desertification and resource depletion. In several regions, drought is forcing farmers and herders to sell their livestock and abandon their land. In el-Naama, located in western Algeria on the border with Morocco, the drying up of wells and the disappearance of pastures have made livestock farming impossible, forcing families to migrate north or to retrain. This precarity primarily affects women, the main victims of ecological disasters.

By 2050, 1.2 billion people could be displaced, 80% of them women and girls exposed to violence and insecurity.

Added to this is the toxic legacy of colonialism: the French nuclear tests carried out in the Algerian Sahara have left deep environmental and health scars, while Algeria remains trapped today between neo-colonial pressures on its natural resources—particularly gas and shale gas—and the extractivist logic of multinationals like Total, which want to impose their vision at the expense of sustainable energy sovereignty. In this war for control over resources, women find themselves doubly trapped: not only are they victims of the ecological and social impacts, but they are also prevented, by the economic choices and finance laws of recent years, from accessing structuring and job-creating projects that are essential to their emancipation.

A feminist and decolonial ecology against liberal greenwashing

Far from the guilt-inducing rhetoric of NGOs, we urgently need to rethink a political ecology that does not serve as a screen for liberal interests. Women in the Global South should not bear sole responsibility for a crisis from which they are disproportionately suffering. The urgent need is not to encourage inappropriate individual gestures but to demand structural transformations: sanctioning multinationals, cancelling ecological debts, and recognizing climate migration as a humanitarian emergency.

Africa, now in search of an industrial revolution to emerge from Western dependence and imperialism, cannot be sacrificed in the name of an ecological transition model that protects the privileges of the Global North above all else. Real climate justice cannot exist without social justice free of paternalistic logic that perpetuates inequalities rather than combat them.

Real climate justice cannot exist without social justice free of paternalistic logic that perpetuates inequalities rather than combat them.

The feminist fight for climate justice cannot be reduced to superficial reforms or individual accountability that obscures the real power relations at play. Ecological inequalities are above all inequalities of power.

Change will not come from international summits. It will come from local struggles waged by the women in the Global South themselves. Ecofeminism is not a mere tool for raising awareness—it must regain its primary function: that of being a weapon of resistance and transformation for women.