This post is also available in: العربية (Arabic) VO

“Don't call yourself a free person if you can't make changes. If you can't stop a genocide that is still ongoing.” This arrow shot by Gazan photojournalist Motaz Azaiza during an interview with MSNBC then again to his one million followers on the X platform has stuck in many of our consciences. The wound is still bleeding after nearly six months of total impotence in the face of the genocide being committed by Israel. If, in the 21st century, we as citizens of democratic countries allied with the aggressor have no means to stop it from committing genocide, then what is this citizenship and what is this democracy we speak of?

We have known horror on a grand scale, and it continues to call to us from the ditches where lie the tens of thousands of disappeared from the Franco era, from the French beaches that served as concentration camps for survivors, from the images of starving men next to piles of bones in Auschwitz… and for three decades, we have seen horror coming from the sea—the sea across which we look to new horizons, but in whose waters we now see the tens of thousands of souls lost to closed European borders. If we don’t have the means to stop our governments from dragging those who seek opportunity, rights, and safety to death, can we call ourselves citizens? Can we call systems that encourage inhumanity democracies?

Palestinian correspondent Anas el-Najar announced that he was ending his press coverage of the genocide in Gaza and said, “The search for safety with my family is a thousand times better than searching for news to convey to a world that does not know the meaning of empathy or humanity.” This was after Israel had killed over 110 journalists in the Gaza Strip along with members of their families.

After a viewer complained about the CBC news coverage of the genocide in Gaza, the Canadian platform’s Manager of Journalistic Standards argued that the Israeli bombings are not “murderous,” “vicious,” or “brutal” (the terms used by the CBC to describe the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023) because the soldiers dropping bombs are located kilometers away from the Strip, and therefore the victims are unseen by their killers and the killers unseen by the victims. For some, any excuse, even a bad one, does the trick.

If, in the 21st century, we as citizens of democratic countries allied with the aggressor have no means to stop it from committing genocide, then what is this citizenship and what is this democracy we speak of?

We are stripping a group of its humanity when we categorize what its members are being subjected to as acceptable knowing full well that we’d find the same situation intolerable if it were happening to our loved ones. You would never think it normal for your nephew to have to risk his life to work in Germany, for your friend to be imprisoned when she finishes her job picking strawberries, or for a population to be expelled from its land to be replaced by another people—let alone for it to be ethnically cleansed in retaliation for the killing of others.

Still, we can live with this reality, because the victims are other. Just that. To dehumanize an entire population, all you have to do is systematically and repeatedly subject it to injustice long enough for the violence to become the status quo. Thirty-five years after the first boat arrived on the Andalusian coast, African shipwrecks still did not elicit any attention or sympathy except when the ships arrived in the dozens or when victims were lost in mass numbers. The policy of fait accompli has succeeded in entrenching in our collective imagination the idea that if you are poor and of a certain race, it is your natural fate to have to risk your life to seek a dignified life. Just like the State of Israel has convinced the majority of its people—through decades of occupation, massacres, ethnic cleansing, and apartheid—that the natural fate of Palestinians in Gaza, those “human animals,” as they call them, is to die at the hands of the Israeli army.

We are stripping a group of its humanity when we categorize what its members are being subjected to as acceptable knowing full well that we’d find the same situation intolerable if it were happening to our loved ones.

But where is our humanity when we are reduced to angry spectators in the face of this barbarism? More people are now avoiding looking at the images of Gazan children stuck under the rubble, of mass graves, of doctors discovering murdered relatives among the patients. It is not because of a lack of empathy that they look away, but because they don’t know what to do with all this pain caused by these images. The feeling of helplessness is suffocating, as is holding all this information without having any channels to transform the information into political action. Knowing things isn’t enough to make us better citizens. It only makes us more aware of how limited our ability to take part in decision-making is. When we feel frustrated that our official representatives are complicit in crimes against humanity, the guilt erodes our faith in democracy itself. Especially when we know that this extent of sadism would be unimaginable had it not gone unchecked for decades.

Impunity legitimizes the unspeakable and renders it acceptable despite the incredulity it evokes when we think of the victims, who are just people, like us. If it is being allowed for all these people to be killed with no accountability, what really is the value of human life?

Combating impunity is therefore a means to preserve humanity. For this reason, we can applaud the work of groups such as Coordinadora de Barrios which continues to fight for justice for 15 people who drowned under a barrage of rubber bullets shot by the Spanish Civil Guard when these people were trying to swim to the coast of Playa El Tarajal in Ceuta. Added to this is the work being done by journalists who are still investigating the truth about the massacre that occurred in 2002 in Melilla, when 23 people died trying to cross the border from Morocco. In this context, we also mention the lawsuit filed by the government of South Africa against Israel on charges of genocide before the International Court of Justice, which has so far received the support of only a small number of countries in the Global South. Punishment is an admission that all these murders were actually committed and that they never should have been, and this is essential for the victims themselves and for their loved ones. But it is also essential so that other people can continue to give meaning to community life.

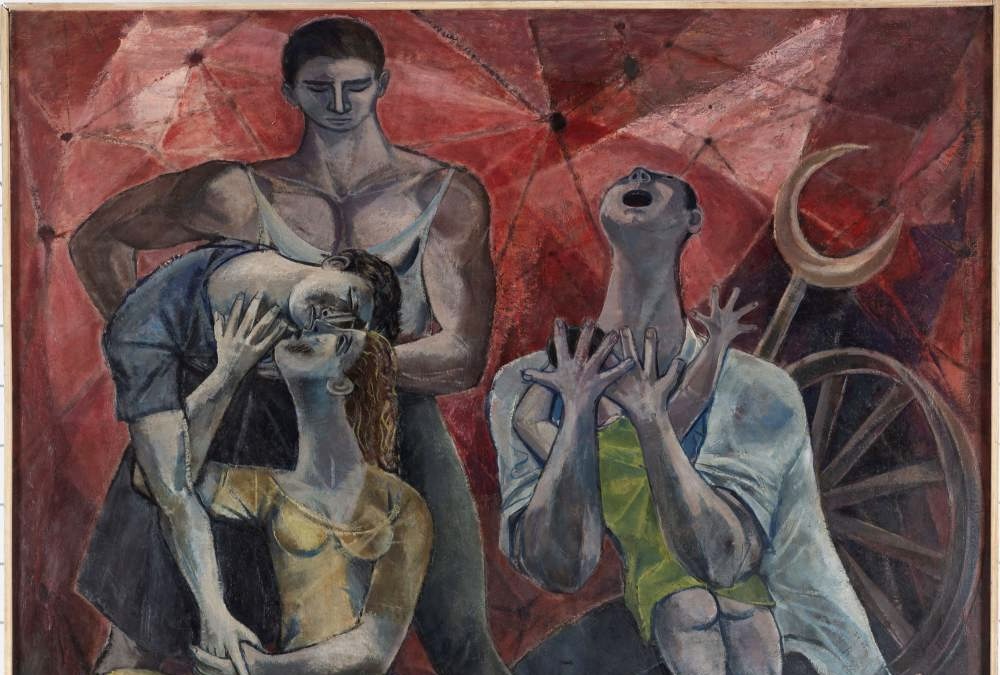

Carlos Martín Beristain, a psychologist with extensive experience in caring for victims of conflicts and in truth commissions, explains that genocide, massacres, and sexual violence as a weapon of war are not phenomena inherent to the human condition. Rather they are the result of systems that have in the past sought to promote the separation and division of groups, which relegated Others to a subhuman category. These systems want only to be obeyed; their authority is imposed. We need to constantly remind ourselves of this to avoid falling into nihilism but also to come out of the daze that has engulfed us throughout these past months as we relive, day after day, the vileness, perversion, and pain that we are capable of inflicting.

Where is our humanity when we are reduced to angry spectators in the face of this barbarism?

Today, now that our existence is threatened by the climate crisis and the return of major conflicts, all intellectual, economic, political, and artistic endeavors must aim to curb this spiral into self-destruction. This is why we must return to a model of humanity—one without which, as Motaz Azaiza warned us, we cannot be free. It is the same conclusion that philosopher María Zambrano reached after the major wars of the last century: “One is only really free when one weighs on no one, when one humiliates no one, including oneself. The human condition is such that it is enough to humiliate, ignore, or make one suffer—oneself or one’s neighbor—for all of humanity to suffer. In every person lies all humanity.”

In an interview on the A vivir program on Radio Cadena SER, father Javier Baeza said, “There is INHUMANITY in all-caps, like the genocide being committed by Israel, and then there is inhumanity in lower-caps, like the one around us, which we can influence.” So it is from here, from our own environments, that we can contribute to rebuilding humanity, by coming together to settle the issue of undocumented people, to defend the right to housing, to boycott Israeli products, to investigate domestic deaths. Because when we come together, not only do we manage to make a difference, but we also protect ourselves from so much injustice—when we realize that we are many, and we are human.

For life to have meaning, we must understand each other. The televised genocide has destroyed the entire philosophical, legal, and cultural framework we established after World War II. If we submit, if we cease our attempts to end this barbarism, we will have accepted to live as prisoners of inhumanity. And that is a fate much worse than feeling helpless, hurt, or angry. It is the ultimate surrender.

This article was first published on lamarea.com