This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

By Inès Atek

You published a detailed article in The New York Times on the living conditions and health and psychological risks faced by mothers-to-be and their newborn babies in the Gaza Strip. How were you able to gather this information when the war and the geopolitical context prevented journalists from accessing it?

First of all, I was in Gaza in August. It was the fourth time I've been there. So I do have some sort of core sense of what Gaza is like. I interviewed regular people and doctors, nurses, and colleagues. I am actively involved in a group called "We are not numbers." This is a group that mentors young writers in Gaza aged 18 to 30. So we have a whole program based in Gaza. All the mentors must be native English speakers. Then I match them with writers. So I have all these connections with folks in Gaza thanks to this writing program. When I was actually asked by The New York Times to write an article, I realized that I also know a bunch of doctors in Gaza and know a lot of people thanks to "We are not numbers." So I started to tell people that I needed to interview pregnant women in Gaza. I managed to reach two people. The thing about talking to people in Gaza is that it is very difficult to get in touch. Because electricity is very rare. The internet is on and off. People are fleeing, moving from place to place, living in tents. But I was able to send a series of questions to this woman, who is a dentist and pregnant*. She has diabetes, so it's a very high-risk pregnancy. We managed to communicate back and forth. And then I was able to interview another woman, who provided me with her background. It's partly luck; her phone worked intermittently. I wrote to her a week ago asking how she is, if she delivered the baby. I got nothing in response.

“Right now, women are not only expected to hold everything together, but they are also blamed when they can’t.”

After all these years of testifying, writing, and thinking critically about the occupation of Gaza, to what extent do you think the situation of women has evolved, or even worsened?

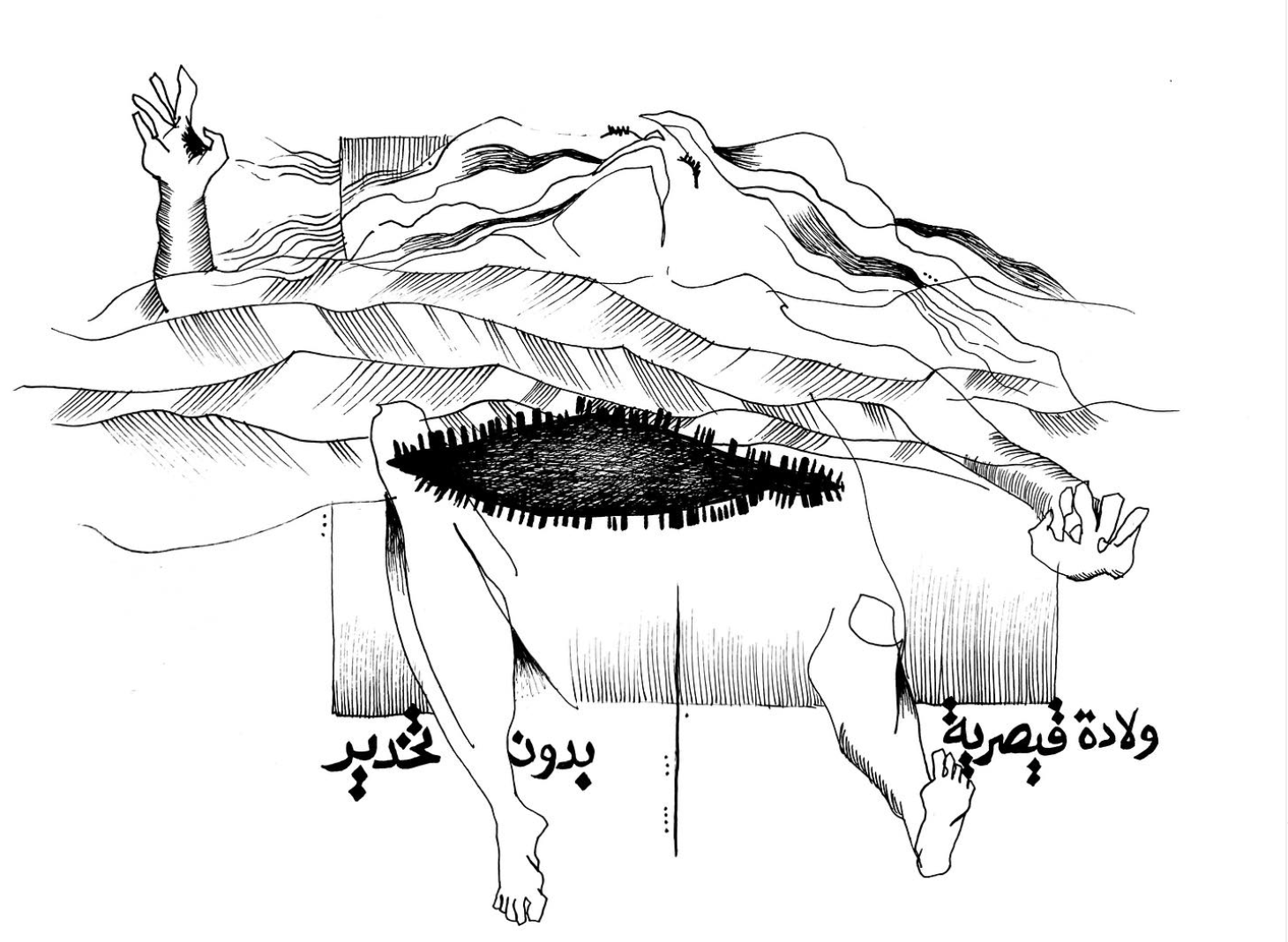

I think that first you need to understand the role of women in Gaza. Of course, there are all kinds of women, from different economic and social backgrounds. Despite those nuances, women are incredibly valued: they are the core foundation of the family, they hold it together. On the other hand, there are also a lot of conservative elements in society, which doesn’t mean that every woman is oppressed by conservative attitudes. But there is a tendency, particularly since the situation got more dire, for women to be pushed back into a conservative role. Right now, women are not only expected to hold everything together, but they are also blamed when they can’t, because there is no food and no money. There is a rising level of gender-based violence. I’ve interviewed women who have been subjected to gender-based violence, who have husbands who were arrested, put in jail for ten years and severely traumatized by the Israeli military just for being Gazan men. Husbands who can’t find employment, who are humiliated at checkpoints and brutalized. So this is a group of men that can inflict their rage and depression upon their wives. This happens all over the world, and we see it happen in Gaza. And if you look at the death and injury rate, women and children are the ones at the front of the war in terms of casualties and injuries. Also, the thing to remember about women in a context of war is that women in Gaza have no hygiene products, they have no pads. If they are pregnant, they have no prenatal care. The women don't know where they are going to deliver. And if they make it to a hospital, they are competing with all the injured people. They don't get all the attention they need, and they have no other choice than to deliver in shelters and tents. More than two thirds of hospitals are not functioning, and it can be very dangerous attempting to get to a hospital. The women are dehydrated, malnourished, so the pregnancy is high-risk. And when the babies come out, they have all sorts of problems because it was not a healthy pregnancy. So there is a particular vulnerability for women, and it's not to be underestimated. Just the issue of pregnancy is itself a major catastrophe.