This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

“Take off your clothes and get up on the table. You can handle the pain, you need to wait your turn.” This is what transpires in public hospitals in the Kebili Governorate in southern Tunisia, as Sarah, 33, tells Medfeminiswiya, recounting the violence she experienced during labor and childbirth—a pain she will not forget.

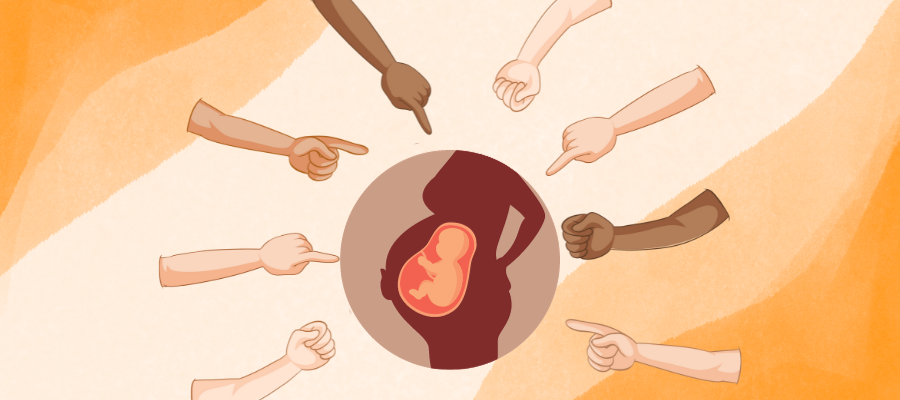

Violence and abuse during childbirth

After what she went through when she gave birth the first time, Sarah says she does not intend to have any more children because of the abuse and the verbal, even physical violence she experienced. “The midwife descended on my stomach with such force that I couldn’t breathe, and she cut my vagina without my permission. I did not find out about this until after I woke up from the anesthesia. I felt severe pain and still suffer from effects of that pain to this day,” Sarah explains.

Many midwives resort to this type of incision in the vagina to speed up the process of childbirth without first verifying that the women in question consent to this. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists this practice as a violent and inhumane form of obstetric violence.

The WHO defines obstetric violence as “a public health problem resulting from the intentional use of force and physical violence, whether it be threatened or actually harming another.”

“She cut my vagina without my permission. I did not find out about this until after I woke up from the anesthesia. I still suffer from effects of that pain to this day.”

In a government hospital located in Tunis, Yasmine tells us she experienced the following: “The midwife forced me to get on the table and stay in the birthing position hours before I was given the injection that would put me into labor. And in the midst of all this, the door to the room was open, and I could see a lot of people passing by: medical teams, nurses, and other people that walked in every now and then. Having left me in this exposed position the whole time, in front of everyone! I asked the midwife to close the door, but she mocked me and said that we weren’t in a hotel on vacation, and that they didn’t close the door around there.”

Yasmine describes with pain and sadness the bitterness of her experience. “I felt the blood freeze in my veins. They thought my request was strange, and I couldn’t believe the way she’d reacted. Don’t these people respect patients’ physical privacy? It’s useful to recall here that the WHO considers forcing women to remain in childbirth position an ‘inhumane act.’”

Discrimination fuels the escalation of violence

In societies where patriarchal systems and mindsets are the norm, the horrors of obstetric violence increase because they intersect with various factors in which social norms play an important role in excusing violence against women. So women keep quiet about the violence they face in hospitals because they know they will mostly be treated as if the violence were normal or natural.

In addition, it’s no surprise that violence multiplies when accompanied by severe discrimination. For instance, when a single mother gives birth, the obstetric violence committed is even more dreadful. The same applies to pregnant women of relatively advanced ages, as they are more likely to be ridiculed.

All of the above has been confirmed by a qualitative study on social standards and the extent of acceptance of the mistreatment of women, published by the Sudanese AMNA Foundation. The study concludes that there exists a social generalization that normalizes the image of a violent midwife—in turn, this normalizes her screaming at or beating women during childbirth.

Most often, and especially in patriarchal countries and marginalized areas, women do not know their rights and coexist with these patriarchal systems and customs that prevail around them. Kholoud Faizi, a Tunisian midwife and feminist activist, explains that “obstetric violence is linked to all stages of a woman’s health care and to all the phases of pregnancy, as any form of verbal violence or mistreatment by medical staff falls under the umbrella of obstetric violence.”

Amid all the complexities of the physical and psychological violence practiced against them, many women suffer from the effects of the incision procedure, whose chronic side-effects impact their physical, psychological, and sexual health. And this all occurs without the women’s knowledge or consent. They are viewed as mere numbers that need to be brought down by accelerating births to be able to receive more and more women, as many as the hospital can hold, keeping in mind the smallness of the rooms and the lack of resources.

Scarcity of resources intensifies the tragic treatment of women

Shortages in medical staff, namely obstetricians, and the lack of resources intensify the tragic treatment women are subjected to. In this context, Faizi explains, “The lack of tools, such as a heartbeat sensor, impacts the quality of treatment and exposes women to serious risks, as some midwives in rural and remote areas are forced to check for a heartbeat by palpation at a time when the fetus may be dead in the mother’s womb—they are not able to check for this through scientific methods.”

Poor women bear the harshest burden of the deteriorating conditions of public hospitals because they cannot afford the cost of giving birth in private hospitals.

Hospitals in remote areas are usually staffed by midwives, who are primarily trained in natural childbirth. But any complications during childbirth such as a weak fetal heartbeat, heavy bleeding, or low blood pressure would require the intervention of a specialist doctor. These doctors are not usually available in these areas, which sometimes leads to the death of both the woman and her child. This actually happens quite often. Perhaps the most prominent example is the 2015 death of a woman in Tataouine Hospital that sparked widespread controversy and discontent within feminist and human rights circles.

It is therefore obvious that poor women in marginalized areas are most at risk of death while giving birth because they rush to public hospitals as they have no alternative, and these hospitals have become unable to provide health services and safe childbirths because of successive economic crises.

These women bear the harshest burden of the deteriorating conditions of public hospitals because they cannot afford the cost of giving birth in private hospitals.