This post is also available in: العربية (Arabic)

Contribution from The Sex Talk Arabic to Medfeminiswiya

Written by Nouran el-Marsafy – Egyptian activist and writer

Have you ever thought about the spaces you occupy? And have you thought, for example, about giving names to these spaces? Or tried to discern your feelings toward them? These might be surprising questions, they may even seem absurd, but I am trying to define what I call “spaces of fear” and their opposite, “spaces of hope”. I’m in the process of figuring out the relationship of these spaces to us, as women, delving deeper into how they shape us but also how we shape them, and how they relate to our feelings and our relationships with our bodies and the world around us. Throughout the following text, I speak from a personal, reflective perspective.

I’m an Egyptian researcher in my thirties. I’m passionate about architecture and feminism, and I practice resistance as an essential part of my daily life. I’m also a founding member of “The Sex Talk- بالعربى” (The Sex Talk-in Arabic) initiative. I started thinking about how to define space after a colleague asked me the following question: “What are the spaces even available for feminists to participate in public space?”

Defining “public space”

Her question made me pause for a moment. She asked it in English, not Arabic, and the question itself pushed me to wonder what my colleague meant by “public space” (or what we call the “empty spaces” in Arabic). What space, exactly, was she talking about? Did she mean the public domain? The definition differs between the two, and, being an architect, I know very well that abstract space doesn’t have any borders for it to be divided into spaces that belong to women and others that don’t. But I also know that, using the inferred definition of “public space”, this space cannot fit me, a feminist activist. Not because it’s too narrow, but because we simply cannot exist in it due to the many political and social constraints, and because all the spaces we try to inhabit are “limited”. Are there even any public spaces for women?

I learned that “public space” is actually used to refer to any space that is not constructed and that is in the public domain, where everyone is guaranteed the right to exist without exclusion, discrimination, discomfort, or fear. And through my political practice, I’ve learned that public space is just the same as the public domain, with the important difference that it is not conditioned by constructed borders and it reflects the methods of communication and the limits to enjoying freedom and being able to express oneself.

In both cases, my personal presence in public space or the public domain remains a personal space that I have wrested for myself, positioning myself within it. I use the word “wrest” here because that space is not truly public, which means the effort I make to ensure my presence within it is a daily one, and I am always afraid of losing both the space and my existence within it, simultaneously.

It was at this point, at this very moment, that the concept and feeling of “fear” crossed my mind. I realized that our spaces, as women, are not public at all—in fact, they are constantly surrounded by fear, which limits and delineates them. I found myself cynically responding to my colleague: “Honey, women’s spaces in general and feminists’ spaces in particular, in our local context, are just spaces of fear. So our spaces aren't really public, and that’s why we have to create our own, in an effort to ‘take up space’…” But before we move on, what exactly is fear, and how did I learn what it means?

I realized that our spaces, as women, are not public at all—in fact, they are constantly surrounded by fear, which limits and delineates them

Let’s start with fear… What is it?

For a long time, fear was my main motivator. I can’t remember a time when something other than fear drove me to take any important step in my life, be it a simple or a difficult step. For example, what clothes I would wear used to be dictated by fear, a fear of social stigmas that govern my body and my ability to show off both its charms and its flaws. I was also afraid that I wouldn't be a perfect student and that my mother wouldn’t be proud of me, and this made me give up sleep for days on end as I studied for endless hours to successfully enrol in an engineering school. Why engineering? For fear of not being able to join a syndicate with good services to offer. And because girls don’t go into mechanical engineering, I went into architecture, fearing the stigmatization that follows female mechanical engineers and their characterization as being man-like.

And that wasn’t even what fear stopped at. It stuck to me with fierce loyalty. How many abusive relationships did I stay in for fear of loss? What’s more, I stopped staying up and going out late with friends, for fear of being on the streets at night. And fear wouldn’t even leave me alone in my own house, where I was afraid of stating my opinions or disclosing the fact that I even had an opinion! I didn’t want to have to get into how I formed those opinions, or the books I was reading, or my feminist inclinations. I didn’t want to start an argument that might somehow prove that I had any kind of self-worth.

I was even afraid to believe that I was someone who had achieved things. I was afraid of countless things, to the point that I had taken fear up as a constant companion. It dominated all the public spaces I knew, even disturbing the public sphere around me, such that I became afraid to express my opinion or object publicly. This is how I started defining spaces of fear (and I must warn you, they are many!).

Spaces of fear, in my understanding, are ones where people, especially women, feel uncomfortable. It may feel like one is being watched, that every action or word uttered could become grounds to be judged and condemned forever, or could provoke the onset of a long, psychologically exhausting argument. Spaces of fear are also those in which a person fears losing. Looking further into the idea of “loss”, I ask myself: We are constantly trying to reach wider spaces and create space for ourselves, but if we didn’t have anything—if I didn’t have anything, would I still be afraid? Afraid of losing? Am I ready to lose my status, rights, and convictions for a bigger-picture gain?

“But if we didn’t have anything—if I didn’t have anything, would I still be afraid? Afraid of losing?”

“Alternative” spaces

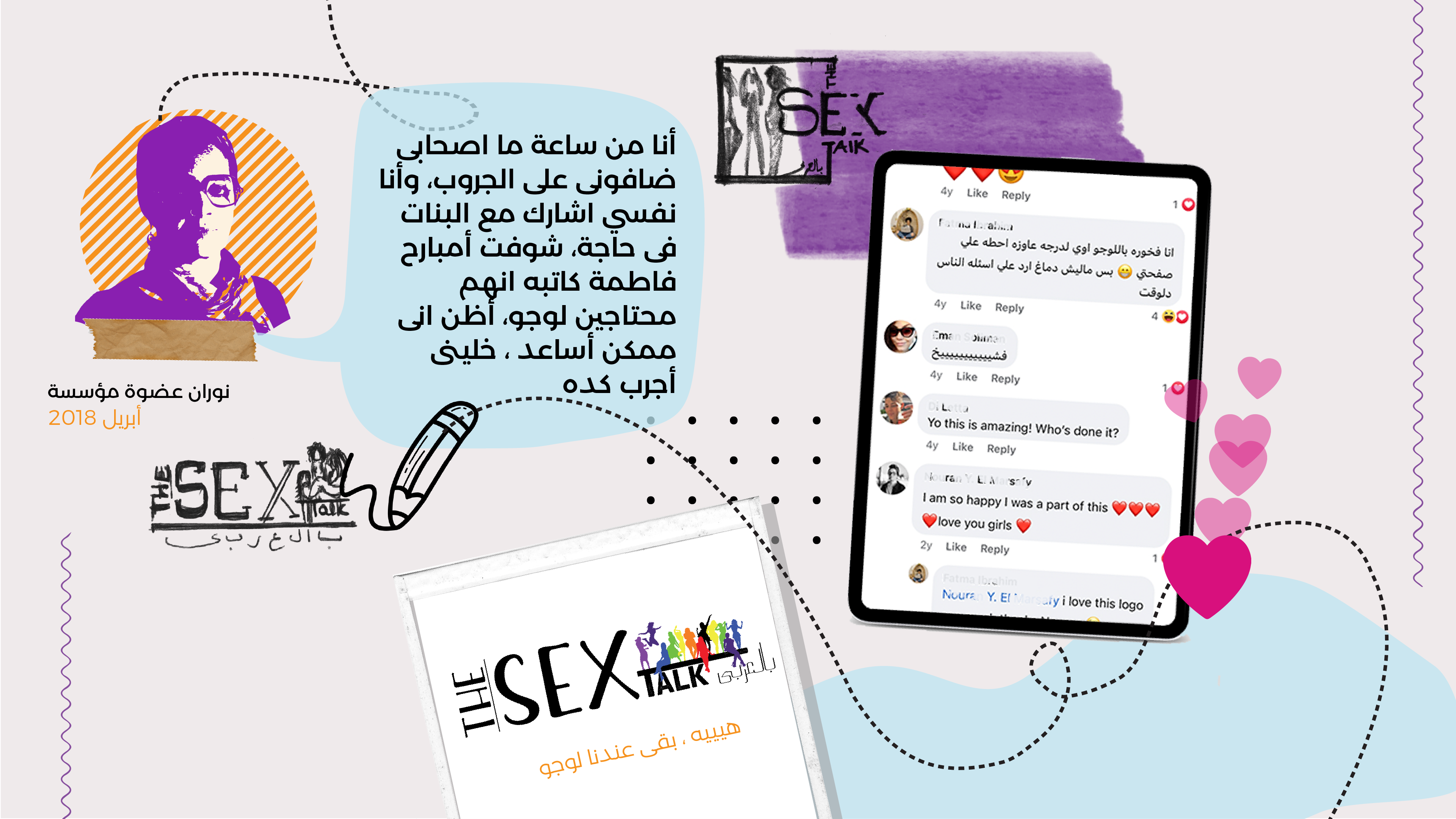

While looking for alternative spaces of hope that could resist the spaces of fear, I clicked a button in 2018 to join a private Facebook group called “The Sex Talk- بالعربى”. Did you just get the same feeling I got when I read that name? The one that elicits a silly smile laced with hesitation, curiosity, excitement, and passion?

That day, I felt equally afraid as I did excited. But a naïve online courage pushed me to write a comment on a post, introducing myself to a group of women I didn’t know. Would this turn into a new space of fear?

I challenged my fear and read through the content posted on that group. The more I read, the more my eyes teared up. I was finally looking at useful information about sexual health and rights “in Arabic” (بالعربى), not in Egyptian dialect or other colloquial Arabic accents. Information about my vagina and vulva, words I used to be afraid to say—information about, let me just say it the way women do amongst ourselves, information about my pussy! I’d finally found women who knew and were convinced that this word is not insulting.

When I clicked on that button, I didn’t know that I was defying fear and that I was about to embark on the journey of co-creating this inspiring, radical, queer feminist group.

After nearly a year of trying to build trust, sharing experiences, and actually impacting the lives of the women in this space, the initiative had to expand and create other, wider spaces of hope. We had to start publishing information in a non-confidential way to allow more women to benefit from it. It couldn’t remain a closed group and it was time for it to become what it had to become: a tool of resistance, and our way to practice our feminism.

As such, the founder of the initiative decided to “open” our horizons and created pages for the group on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and all these pages were posting feminist content, in Arabic, about sex, sexuality, and sexual health and rights. This was at a time when feminist initiatives, in general, would rarely address topics like masturbation or LGBTQ rights, to name a few. The initiative picked up with the cooperation of many female volunteers who helped the pages become what they are today. They helped increase the pages’ reach very quickly, and this brought pride, but fear as well.

When the project was going through this growth, I decided to participate in a more active, clearer way. I was definitely afraid of the consequences, but I didn’t waver and used my skills to contribute to designing, drawing, and producing visual content. My face never appeared on any product or material, but I still used to think, what about the founder? Did she not feel afraid? Did she ever feel afraid of being identified as who she was? Was she afraid that the world would find out that she was the one behind this content? How did she feel in those first moments when she appeared in the “online space” to talk about women’s sexual rights? I kept mulling over all these questions, then I said to myself, firmly: she must be afraid, too.

Fear... you again! Should we even assume that spaces of fear and our other, alternative spaces are mutually exclusive? The answer is no. Unfortunately, spaces of fear continue to exist as long as we do, and they are represented in every space outside that of hope, threatening us and our alternative spaces.

Spontaneous sisterhood in the face of fear

By simply leaving the spaces of hope that we deem safe to wider spaces, we are actively not conceding. Not to the attempts to shut down the page, not to bullying, not to online harassment, and not to the threats to report the page to the authorities. But this fear was bigger than the virtual space we occupied. We are all volunteers, so we have to work in other places to secure our livelihoods, which means we need to constantly be aware of how vulnerable we are in social circles that do not embrace what we are fighting for. Between 2018 and 2021, I didn’t even dare reveal my affiliation with the group at my place of work. I was afraid I’d get bullied or lose my job.

But since we decided to leave our safe space and reveal our identities, thus challenging the spaces of fear and gender-based violence online, I started to notice something that gave me hope, and I was noticing it every day of my life: sisterhood. The sisterhood that brings us together as women and founders through our spontaneous creation of these spaces. It is based on the belief in the value, rights, and diversity of women. We have encouraged other women to work with us to help challenge conservative publishing standards and ensure continuity, and many have joined us, despite the lack of financial resources. We have all come together without ever having met or even seen each other’s faces, sparking what I refer to as a spontaneous sisterhood.

I thought then that fear was surely gone. But what happened after the wide launch alerted me to a new kind of fear. The one that stems from a sense of responsibility, from a mixture of various responsibilities, mainly those placed on us as the team leading this initiative: deciding what to do, how to secure funding, how to ensure the continuity of knowledge production, keeping our participants safe, and the handling of difficult questions.

“How do we consolidate our diverse approaches to raising issues while still ensuring the fair representation of our differences and celebrating our diversity and individuality?”

How do we consolidate our diverse approaches to raising issues while still ensuring the fair representation of our differences and celebrating our diversity and individuality, our uniqueness as a group? Do we change our approach to become less radical to ensure cyber safety and security in countries with difficult political and police situations? Do we keep addressing issues that are shocking to Arabic-speaking societies? Do we write anonymously? Do we share our sources? Will our daily decisions and discussions affect the volunteers on a personal level, impacting their safety and psychological security?

We agreed that our activisim lies in our radical approach and in the fact that we took on this bold initiative, challenging the prevailing silence that encourages violence against women. We also agreed that the security, well-being, and mental health of the women working with us are essential and cannot be overlooked. In doing so, we were unknowingly developing a plan to systematically challenge fear, and we decided as a team to take some measures to address the cyberspace and the dangers it exposes us to.

We started by training members on digital security and making sure that everyone knows how to deal with cyberattacks. We also developed collaborative security policies that reflect the frameworks governing how to deal with attacks and the platform according to geographical location. This marked a shift in our relationship to technology, as we stopped viewing it solely as a threat and embraced it as a means that can be used in ways that keep us safe instead of just exposing us to danger. We now use programs that help prevent our platform being hacked. We also took the initiative to create our own website to ensure the security of all participants and to prevent any stalker from accessing members’ personal pages.

But is that it, is the work done now? Far from it. We are still trying to fully integrate these spaces and increase the amount of safe spaces so we can reach a greater number of women and members of the LGBTQ community to solidify their right to take up space.

In conclusion, I don’t know if the steps we’ve taken are enough to eliminate fear, but what I am certain of is that resistance is part of our daily lives, and there is no escaping it. It’s the result of our attempts to surpass the spaces of fear, to surpass feeling afraid. I’m actually grateful to fear, personally and deeply, and I find myself thanking it for always pushing me toward horizons I never even knew I could reach. Here I am, reaching them…

Additional readings recommended by the author:

أشكال التهميش الرقمي للنساء بين الابتزاز والإسكات العام, مركز المستقبل, هدير أبو زيد

Kämmerer, A. (2019) The scientific underpinnings and impacts of shame, Scientific American.

المجال العام من الواقع الفعلى إلى العالم الافتراضى : معايير التشكل والمعوقات, المركز الديمقراطى العربى

عبد الهادي سحر إسماعیل محمد (2018) الأبعاد الاجتماعية والتکنولوجية وتأثيرها على تشکيل الفراغات العمرانية بالمدن (دراسة حالة الفراغات العمرانية بالإسکان الحکومي)

مجال عام، ويكي جندر

Manion, Jennifer C. “Girls Blush, Sometimes: Gender, Moral Agency, and the Problem of Shame.” Hypatia, vol. 18, no. 3, 2003, pp. 21–41. JSTOR