This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic) VO

Click here to read the original Italian version of the article.

Between 2017 and 2019, Kurdish journalist, artist and feminist Zehra Doğan served a two-year and nine-month sentence in the country's toughest prisons on charges of terrorist propaganda for posting on Twitter a drawing of the town of Nusaybin destroyed by the Turkish army. In prison, she made numerous paintings, using makeshift canvases and recycled organic materials instead of colours, and the first graphic novel written in a cell: 'Prison No. 5'. With her work she claims freedom and justice for an entire people by denouncing the atrocities of an increasingly authoritarian and repressive regime.

As a journalist, she had often documented the clashes in Turkey's Kurdish cities, and with a report on Yazidi women in 2015 she had won the prestigious Metin Göktepe award. Yet no journalistic investigation had ever triggered the fury of the Sultan as much as that graphic elaboration of a photo taken by a Russian soldier at the end of the siege.

She was still a prisoner when, in 2017, she wrote to Italian journalist Francesca Nava who was in Turkey to shoot a documentary about women persecuted by the regime for their support of the Kurdish cause.

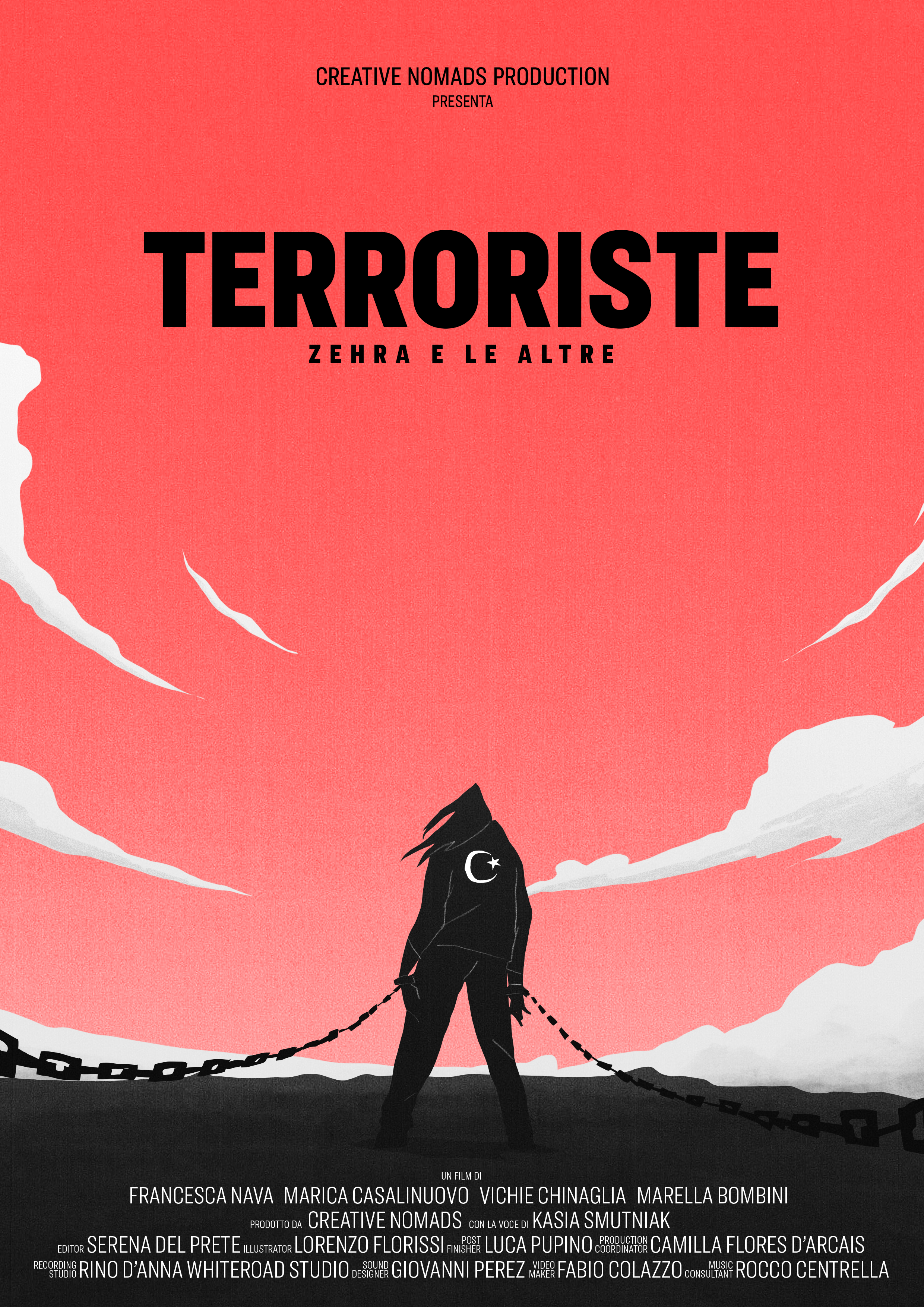

Created by an all-female team, ‘’Zehra and the others - Terrorists" ( Italy, 52', 2019) mixes journalistic investigation with original animation and footage by local filmmakers who do not appear in the credits for fear of repercussions.

"Zehra had been arrested a few days before our arrival and through her lawyers we got in touch with her, who replied with a touching 22-page letter," says Francesca Nava. ‘’Right away we decided to turn it into the thread of this story that speaks of the struggle of a woman, and through her of an entire people, the Kurds, a people of which she has become the spokesperson with the most powerful weapon in the world: art."

In the documentary, her story is intertwined with that of two other women, Turkish ones: the journalist and writer Aslı Erdoğan and the physician, professor of forensic medicine and internationally renowned activist Şebnem Korur Fincancı.

Accused by the government of being terrorists and PKK supporters like Doğan, they were both imprisoned and faced severe threats and intimidation by the authorities.

Aslı Erdoğan was arrested because of her column in Özgür Gündem, one of the country's leading pro-Kurdish newspapers, where she denounced the government's constant human rights violations for years.

After the 2016 coup d'état, the newspaper was ‘’temporarily closed’’ and 20 of its journalists ended up in custody: she still remembers, terrified, the day when 50 men with covered faces, bulletproof vests and automatic rifles burst into her house to arrest her.

"The history of the West, including Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union, has never seen so many writers and journalists in prison," comments the author, recalling over 80,000 people arrested, including 319 journalists, 170 thousand layoffs, approximately 3 thousand schools and universities closed and almost 200 censored media outlets. “I have no regrets; I wrote the truth. Honestly, I’m very scared of going back to prison but I would do the same thing, write the same articles,” she concludes.

Şebnem Korur Fincancı has documented and reported many cases of torture in her country and abroad as a forensic pathologist and medical examiner. In the late 1990s, she contributed to the drafting of the ‘’Istanbul Protocol’’, published in 2001 by the United Nations as an international guide to legal and clinical investigations for recognizing signs of torture and ill-treatment.

When she took part in the solidarity campaign for the daily Özgür Gündem by becoming its ‘’editor for a day’’ in 2015, she was charged with ‘’terrorist propaganda’’, ‘’justification of criminal acts’’ and ‘’incitement to crime’’, and imprisoned for 10 days.

"The real reason she was arrested was the Cizre Report she had signed a few months earlier,’’ Francesca Nava points out. "In that document, later censored by the government, she had in fact demonstrated that among the 143 people sheltered for days without food or water in a basement in the Kurdish city under siege there were no PKK guerrillas as Ankara claimed. Thanks to the autopsy she carried out, it was possible to reconstruct the jawbone of a 10-year-old child.’’

Fincancı was arrested once more last October for calling for an independent investigation into the Turkish army's use of chemical weapons against Kurdish militants in northern Iraq and was sentenced to two years, eight months and 15 days in prison on 11 January 2023. "This is not a legal trial but a political one," she commented after the sentence. "It is a trial that aims to politically kill the Turkish Medical Association and the principles of democracy."

“The history of the West, including Nazi Germany and the Stalinist Soviet Union, has never seen so many writers and journalists in prison"

Hundreds of other women in the country struggle every day against the censorship, silence and repression imposed by the regime, like the young journalists of Jinha Agency, an underground pro-Kurdish and feminist multilingual news agency. "We are a self-sufficient cooperative, we use a new all-female vocabulary, we are all women. In the beginning we were five, now we are 100 women journalists from all over Turkey. During the state of emergency, they blacked out our site with an executive order and we were declared traitors,’’ Nalin Öztekin tells in the documentary. "Had it not been for our work, the world would never have known the truth about the horrors committed in Cizre, Sur, Nusaybin,’’ adds Rojda Oğuz, who was also arrested on terrorism charges. ‘’We are the journalistic version of the Amazons: we fight with our writing and our cameras against violence against women and for peace.’’

An increasingly worrying situation

Real time data from Reporters Without Borders shows that 548 journalists and 19 media workers are currently detained in Turkish prisons and that the country is 149th out of 180 in the press freedom ranking.

Amnesty International's latest annual report highlights some particularly worrying events in 2022. These include the bill presented in October by the ruling party (AKP) and the nationalist movement (MHP) on disinformation and fake news, which toughens the penalties for professionals accused of "publishing false content aimed at instigating fear or panic, endangering the country's internal or external security, order and public health." Amnesty and numerous international press freedom observers argue that the measure legitimizes online censorship and criminalizes the profession, intensifying the already very heavy-handed government control over the few remaining independent media.

"Portraying the Kurdish people as an enemy of the state is a strategy Erdoğan has always used to legitimize and strengthen his nationalist and securitarian policies and to distract public attention from the country's real problems: the severe currency and economic crisis, the disastrous consequences of last February's earthquakes, and the very grave violations of human rights,’’ explains Francesca Nava.

"Persecuting and punishing female journalists allows the government to cover up and manipulate compromising news, as in the case of Can Dundar, (former) editor of the main opposition daily, Cumhuriyet, who was sentenced in absentia to 27 years in prison for having published in 2015 a video in which Turkish intelligence agents prepare a truckload of weapons destined for jihadist groups in Syria close to Al Nusra.

In recent months, the situation has become even more tense ahead of the parliamentary and presidential elections (in May), which constitute a delicate test for the current government and the entire country.’’