This post is also available in: Français (French) VO

Contrary to what one might think, the act of looking into the past does not always constitute a consoling plunge that risks cancelling contact with and adherence to contemporaneity. I have experienced this recently, when in 2021, I republished in Voi siete in gabbia, noi siamo il mondo- Il femminismo al G8 di Genova (“You are in a cage, we are the world – Feminism at the G8 of Genoa”), several documents of the feminist network of the time that gave birth, in June 2001, to the event PuntoG-Genova, genere, globalizzazione (“GPoint-Genoa, gender, globalisation”), a month before the demonstrations of the Genoa Social Forum of which the network was part.

In every book presentation, thematic meeting and discussion I have participated over the past year, there have always been people to stress how the analyses generated at different historical moments of feminism are still very relevant today. However, those who made this observation often looked at it from a negative perspective, concluding that after twenty years, we are still at square one.

I always reply that, on the contrary, I believe it is a blessing to recognize the topicality of these contents. It is indeed a demonstration - and we should be proud of it - of the way in which there is a strong link, coherence and resilience in feminist thought despite the passage of time, between founding concepts, which do not lose their strength, and reason. And this, despite the deleterious sirens of the “new”, this dangerous illusion according to which everything that presents itself as new, and apparently disturbing, is always synonymous with innovation and freedom.

On the contrary, it is fundamental to draw inspiration from the enormous reservoir of material and knowledge developed by previous generations of feminists and to draw upon and confront the contemporaneity of feminist thought and practice at different times.

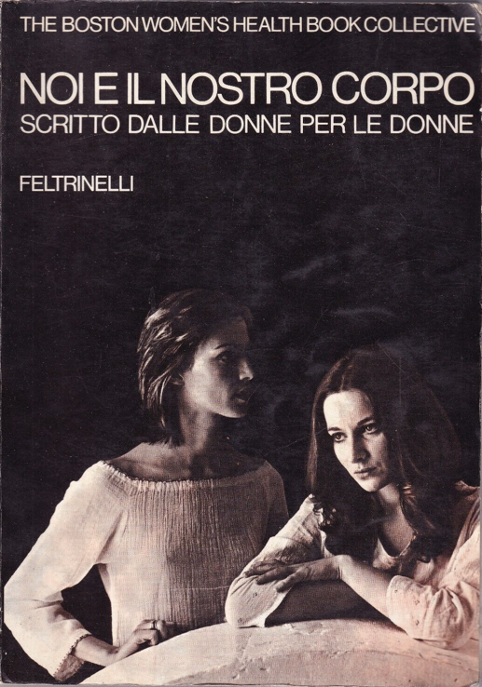

That is why I am grateful to Vicky Franzinetti - translator and feminist activist from Turin – who, together with Filomena Rosiello, one of the three co-presidents of the Casa delle Donne in Milan, organized an online meeting of major importance. This brought together three of the twelve North American activists of the collective, which, in 1977, after a year’s work, published one of the key texts of world feminism: “Our bodies, ourselves”. (Downloadable here for those who do not have the printed text).

Norma Swenson, a splendid, in her nineties, Judy Norsigian and Jane Cottingham, both in their eighties, and founders of the Boston Women's Health Collective who authored the famous volume, spoke with Vicky and Filomena on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the book. Passed down from hand to hand, from woman to woman (often from mother to daughter) for several generations, this book is a precious and timeless heritage, an essential viaticum to begin the journey of consciousness, and therefore of freedom, within and with our own bodies.

The moving account of the three protagonists of this thrilling moment in the history of feminism restores the pragmatic and eminently political spirit of the text, in the introduction of which one can read considerations, which, intact, echo the experience that every generation of women remembers. Getting to know our body has radically changed our lives and ourselves. It is wonderful to study when what we feel emotionally and what we learn are two parallel closely related and intertwined experiences.

Sexuality, pleasure, desire, pregnancy, childbirth, abortion, menopause, rights and sisterhood are just some of the keywords on which the collective worked to consign to history the first feminist encyclopedic compendium on women's bodies.

With regard to topicality, here is a passage from the text -which was published in Italy in 1977 but was printed in the United States four years earlier- on the stereotype of the aging woman:

“The popular image portrays the postmenopausal woman as tired, intractable, irritable, shrewish, unattractive, unbearable (yes, her husband is right to seek out the company of another woman), irrationally depressed, terrified of the change in her (re)productive life. Our idea of menopause may have been influenced by an advertisement similar to the one that featured in a well-known medical journal, in which an obviously bored middle-aged man appears next to a dull, tired-looking woman. The type of medicine advertised fights "the symptoms of menopause that trouble him so much".

It is wonderful to study when what we feel emotionally and what we learn are two parallel closely related and intertwined experiences…

In the 1973 introduction, the members of the collective, all of whom are involved in various capacities in medical and psycho-sociological research, provide us with considerations which, even today, form the basis of all training and set the preliminary framework for support groups for women of all ages and conditions:

“Imagine a woman who is trying to do a job and have an equal and satisfying relationship with others, but in the meantime feels physically weak, because she has never tried to be strong; she uses all her energy trying to change her face, her figure, her hair, her smell to conform to an ideal model established by magazines, films and television. She feels disorientated and ashamed of the monthly blood flowing from some dark corner of her body each month; she experiences the processes inside her body as a mystery that only appears as a nuisance (an unwanted pregnancy or cervical cancer): she does not understand or enjoy sex and focuses her sexual energies in purposeless romantic fantasies, perpetuating and misusing her potential energy because she has been brought up to deny it. If we learn to understand, to accept, to be responsible for our physical identity then we can free ourselves from these injunctions and begin to use our uninhibited energies. Our self-image will have a stronger foundation; we will be better as friends, as lovers, and as people. We will have more self-confidence, more autonomy, more strength, we will be more complete.”