This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

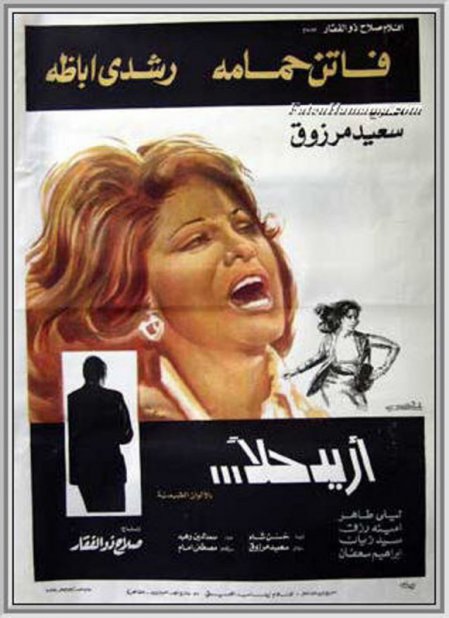

Main image: Divorce is a topic that is often discussed in Egyptian films. Here, I Want a Solution by Samir Mazhar, 1975.

Mona Mahmoud, 26, never imagined that she’d be left alone during the most vulnerable time of her life. Her husband divorced her in absentia when she was six months pregnant, leaving her to face childbirth without support. Her fear intensified as the time for the baby’s arrival approached, and when she underwent a cesarean section, her concern wasn’t so much the pain as the fate of her child. Would he be legally recognized? Or would he be denied a birth certificate proving his existence?

In a society that ties birth registration to the signature of the father or one of his relatives, Mona worried that her son was at risk of being born nameless. “I was living a nightmare,” she tells Medfeminiswiya. “Every night, I asked myself: what if my husband refuses or ignores me? Will my son lose his rights just because his father chose to disappear?”

Mona carried these fears in her hands and went from one law office to another with her marriage and divorce papers, trying to prove her son’s right to exist even before his birth. She stood at the gate of the civil registry, determined that her son not be erased from official records before taking his first breath.

Her lawyer advised her to file an official report and summon her father or brother to stand in for the absent father. From there began an arduous journey through layers of bureaucratic procedures, starting with notifying the husband to sign the birth certificate. No one knew when or how this process would end.

Divorce in absentia has become a repressive tool that some men use to evade their economic obligations to their wives—from alimony and housing to their inheritance rights.

Stories that show the magnitude of the disaster

But Mona’s tragic situation is far from being an exception. Asmaa el-Sayed, 37, found herself facing a new kind of betrayal after 11 years of forced marriage. “I married him against my family’s will,” she recalls, “and they disowned me because of it. He exploited my isolation and used to beat and humiliate me constantly.”

As their disputes escalated, the husband disappeared, abandoning his responsibilities toward the family. Under the pressure of mounting financial burden, Asmaa took legal action to claim alimony for herself and her two children. His response was even harsher then: he threw her out of the marital home and sent her back to her family’s home.

The court ordered him to pay 10,000 Egyptian pounds (approximately $200) a month. He became furious and divorced her in absentia to reduce the alimony. And the amount did drop, to a mere 6,000 Egyptian pounds (approximately $120), before he disappeared for years, never checking in on his children or offering them any support.

While Mona and Asmaa’s stories reveal one form of marital betrayal, the story of Maha Abdullah, 50, is doubly cruel. After 25 years of marriage, she discovered that she had been divorced in absentia for many years—without even knowing about it. Her husband did not tell her. He kept it a secret until his death. When she renewed her ID card, she was shocked to discover that she was no longer legally his wife and that she had been deprived of her inheritance and his government pension—just like that.

“It was a huge psychological shock for my mother when she found out that she was divorced even while living with my father all those years,” her daughter tells us. “She supported him when he was sick, working, helping him out.”

Divorce in absentia has become a repressive tool that some men use to evade their economic obligations to their wives—from alimony and housing to their inheritance rights.

How does a wife lose her right to know about her own divorce?

These three stories uncover the reality of how women are left alone in the face of slow laws and outdated customs. According to data from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, more than 200,000 cases of divorce are recorded in Egypt every year, nearly half of which are issued in absentia. Thousands of women find themselves trapped in a legal and social vacuum that compounds their suffering.

The root of the problem lies in the practical implementation of the legal text regulating the procedures for documenting divorce and notifying the wife. Article 5bis of Law No. 25 of 1929 requires the husband to register the divorce with the competent notary within 30 days of its occurrence, and the wife is considered informed of it if she is present during the registration process. If she is absent, the law requires the notary to formally notify her of the divorce. But this procedure, which is supposed to ensure that the wife receives the notice, often becomes a mere formality, as the notification may be delayed or circumvented through the use of inaccurate addresses. As a result, the woman may remain unaware of her legal status for months, sometimes even years.

Legal violence against women

Commenting on these cases, Aya Hamdy, a lawyer at the High Court of Appeal and head of the women’s support offices at the New Woman Foundation (NWF), says, “Divorce in absentia is a harsh legal and social loophole disadvantaging women, as they are often unaware of the date it occurs, preventing them from claiming their financial entitlements: compensatory alimony, the ‘iddah maintenance, and deferred dowry.”

She explains that a divorce in absentia, occurring without the wife’s knowledge, automatically results in the loss of some of her financial rights, most notably alimony, which is due for only three months from the date of divorce. If the woman is not notified within this period, her rights are permanently lost. She also loses the opportunity to claim compensatory alimony, nafqat al-mut’ah, a financial entitlement recognized by both Sharia and the law for the divorced wife. It is usually calculated as at least two years’ alimony, as well as the deferred dowry, which would otherwise be payable at the appropriate time.

Hamdy adds that this type of divorce often takes place before a religious notary, without an official document, unlike divorces processed through the court. This makes it more difficult for women to claim their rights. “Many of the women who come to my office never received any notification of the divorce and were shocked to discover at the civil registry that they had been divorced for a long time without knowing about it,” she says.

“The danger of divorce in absentia is not limited to the loss of financial rights but also extends to moral humiliation and the undermining of a woman’s status. A husband may continue to live with her as his wife even though she is no longer legally his wife, or a woman may discover after his death that she is excluded from his inheritance because she had been divorced for years,” Hamdy elaborates, noting that these practices are particularly prevalent in cases of second marriage, or when older men marry younger women.

“Divorce in absentia is a form of social enslavement of women.”

Dozens of women are divorced in absentia every day in Egypt

The latest data from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) indicates that more than 606,000 divorces were registered in Egypt in 2023, of which 255,000 were documented before a religious notary—representing roughly 96% of all cases—while the remaining cases were registered through court rulings. Although the agency does not specify whether all of these divorces occurred in the presence of the wife or in her absence, according to CAPMAS, about 51% of divorces in Egypt are recorded in absentia—that is, when a husband divorces his wife before a religious notary without her direct knowledge, with notifications sent to her later through an official record or legal announcement.

Approximately 2,547 new marriages are registered for every 728 divorces. Analyzing the numbers shows that nearly 30 divorces in absentia are registered every day.

Systematic social oppression against women

In this context, MP Farida El Choubachy states that divorce in absentia constitutes a form of systematic oppression against women, as it “violates the dignity of Egyptian women and opens the way for men to evade their financial responsibilities toward them.” She points out that some husbands resort to this type of divorce to control their wives’ fate, depriving them of their right to remarry or freely choose an alternative life.

El Choubachy concludes, “Divorce in absentia is a form of social enslavement of women.”