This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

The living conditions of Ivorian women are marked by discriminatory practices, dehumanization, and gender-based violence, and these women are also mostly undocumented migrants—which favors their exploitation even further.

Lydie, 47, from the Ivorian countryside, arrived in Tunisia in 2018 with her son and three nephews, for whom she is responsible. In Abidjan, she worked in a store for a monthly salary of 250 TD, the equivalent of 74 euros. One day, one of her boss’s best clients approached her with a proposition: “He was the one who talked to me about Tunisia. He assured me that I’d get paid no less than 500 CFA Francs there for the same work I was doing in Côte d'Ivoire—that’s 3,500 dinars per month, or 1,200 euros. He said he’d cover the travel expenses, the plane ticket, and hotel reservation, and asked me to take 500 CFA Francs with me to give them to an Ivorian friend of his who would welcome me in Tunis and set me up at my new job. But contrary to our agreement, the Ivorian intermediary to whom I gave the agreed upon sum as soon as I arrived took me to a family in Jendouba, where I had to do housework seven days a week for five months without a penny in return. I slept in the garage and didn’t have enough to eat. My passport was confiscated by the family, and I wasn’t allowed to leave the house.”

She was a victim of trafficking which has been ongoing between Côte d'Ivoire and Tunisia for almost eight years now, managed by a mafia network consisting of Ivorians and Tunisians. Lydie understood a month into her recruitment into this family from a small town in the country’s northwest that she’d been doubly scammed—particularly when the mistress of the house informed her that she was working there “under contract.” Her new boss explained to her that she had already paid the intermediary, who’d promised her a few months’ service from an Ivorian domestic worker. Lydie was told by her boss that she would only receive a real salary at the end of her contract. She was taken over by shock, anger, and despair. She hadn’t had a clue of the reality awaiting her in Tunisia.

The ordeal of a life under contract

“I cried all the time. I was working around the clock, and the lady was very strict with me. But I said to myself that I’d calm my heart down and accept this situation I was in, only until I could get my hands on my passport and free myself. I also felt like I was at the end of the world: I didn’t know the country and didn’t have anyone to confide in,” Lydie remembers.

Noémie also found herself in a situation very similar to that of Lydie. Noémie is 36, also from Côte d'Ivoire, and has three children, left in the care of her sister. She landed in Tunisia in May 2022 after a seemingly fortuitous meeting with a compatriot who sold her the dream of what Tunisia was, and could be, for her: a flourishing country with very easy access to the Italian coasts. He even outlined a clandestine route that she could take towards Europe after a few months’ transit in Tunisia, where he told her she would collect—thanks to a Tunisian friend of his—the price of her crossing, in exchange for taking care of the household of a lady without children. After she reimbursed the Tunisian intermediary, who met her at the Tunis airport, the latter, taking advantage of Noémie’s ignorance of the exchange rate, converted 500 CFA Francs, her pocket money—all her savings—against 100 TD, or 30 euros. The man then took her to a family living in the wealthy district of Ennasr, in the residential suburbs of Tunis. And he left her there, without giving her any address for her to reach him at. For four months, she suffered all the constraints of a domestic life “under contract”: confinement, the confiscation of her passport, and nonstop work from which she didn’t even derive any financial benefit.

“The intermediary told me I still had debts to pay to cover my travel expenses, so he negotiated with my bosses for him to receive the entirety of my wages for the duration of my contract: 2,500 TD, or 740 euros. The work was hard in this family of four. Besides housework, I also had to do the groceries, gardening, and take care of their elderly, infirm father. At night, he screamed when he fell out of bed, and I had to get him back up into bed. He woke me up at all hours of the night. It was exhausting. I got sciatica after my contract expired, but the mistress of the house refused to get me treated or give me a few days off. She even hit me and said that “If you’re sick, you have to leave. We didn’t hire you to stay in bed.” I couldn’t take it anymore. I got my hands on my passport and got out of there.”

There are many stories like those of Lydie and Noémie. Some of which are even more difficult to hear. Sally, 27, trapped in the household of a large family, had to endure the man of the house who had taken the habit of rubbing himself against her backside every time she was in the kitchen alone. She spoke up, but to avail. She had to get the ordeal filmed to prove to her bosses that she was telling the truth. Natacha, 36, wasn’t allowed to use disinfectant gel during the COVID pandemic. What’s more, her boss forced her to come into direct contact with bleach, with bare hands, and to clean the floors with it without even letting her put sandals on. The result? Damaged fingers and respiratory problems*. Marie, 29, lost her three-month-old baby a little less than a year ago: she had entrusted him to an Ivorian daycare center, but he hadn’t survived the carelessness of the place. Depressed, she is surviving thanks to community solidarity…

“I got sciatica after my contract expired, but the mistress of the house refused to get me treated or give me a few days off. I couldn’t take it anymore. I got my hands on my passport and got out of there.”

There are, however, some bosses who behave differently in these situations. Christelle, 40 years old and a mother of three, arrived in Tunisia in 2018 and was lucky to end up at the house of a lady who turned out to be humane and understanding. “Even though I was working under contract, she didn’t hesitate to give me money and let me go out whenever I wanted to the hair salon by her house. I went there to practice my passion: hairdressing and aesthetics.”

Human trafficking: a history of the sector

The trafficking of Ivorian women began around 2014, two years after visa requirements were lifted for travel between Tunisia and Côte d'Ivoire. The country which had spurred the “Arab Spring” had taken this initiative because several Tunisian companies in major work sectors, international trade, and catering had been registered in Côte d'Ivoire. Originally, Tunisia’s intention was to facilitate the movement of local promoters to the sub-Saharan continent. But now human trafficking networks have rapidly been set up on both sides of Africa. A business that is both shady and lucrative: it benefited from the political unrest in Côte d'Ivoire between 2010 and 2011, the soaring inflation of the country’s economy, the very low salaries of its workforce, and the endemic unemployment plaguing its youth. All this helped create these trafficking networks. And then it came into contact with a gap in the Tunisian context: in Tunisia, the housekeeper profession is socially looked down upon, which has meant that the sector has been struggling to recruit workers for the past two decades. Especially when it comes to live-in housekeepers who reside in their employers’ houses and share in their privacy. Expected to be at their service 24 hours a day, these housekeepers are allowed, in some cases, to take one day off a week. Despite the low supply, the demand remained very high for two specific categories of household help: the “sleepers” and the “in-and-outs,” the latter designating the Ivorian women who leave at the end of their shifts in the late afternoon to return the next morning. Gendered from the very beginning, this type of work has gradually also become racialized in Tunisia because it takes advantage (notably for remuneration, which rarely exceeds 750 TD, or 220 euros) the vulnerability of sub-Saharan women, most of whom are living in illegal conditions in Tunisia because of legislative restrictions governing the stay and work of foreigners.

A continuum of violence

According to the national survey on international migration published in 2021, the foreign population living in Tunisia is equivalent to 59,000 individuals (5% of the entire Tunisian population). The survey reveals that the immigrant community from African countries outside the Maghreb (Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, and Mali) has recorded the strongest growth in recent years: its estimated workforce increased from 7,200 people in 2014 to 21,466 at the time of the survey. The Ivorian community takes first place, representing nearly 70% of sub-Saharans entering Tunisia. According to a study entitled “Life Paths of Migrant Women in Tunisia” carried out by Tunisie Terre d’Asile in 2020, the migrant women who are victims of trafficking and who seek out the Association’s offices are mostly of Ivorian nationality (79%). They say they came to Tunisia in search of job opportunities or because they’d already found work in this country.

“This form of trafficking is a source of multiple types of interwoven violence. From recruitment in the country of origin until the end of the said “contract,” women are made to suffer economic violence comparable to modern-day slavery. The types of violence in the workplace reported by women of sub-Saharan origin are multiple: physical violence, accusations of theft, deprivation, threats, sexual harassment, molestation, moral harassment…” points out Marta Luceno Moreno, a researcher at the Beity Association, which carried out—among other studies—a qualitative study in 2021 on “Violence against women and migrant girls in Tunisia.”

Tunisia’s undocumented workers

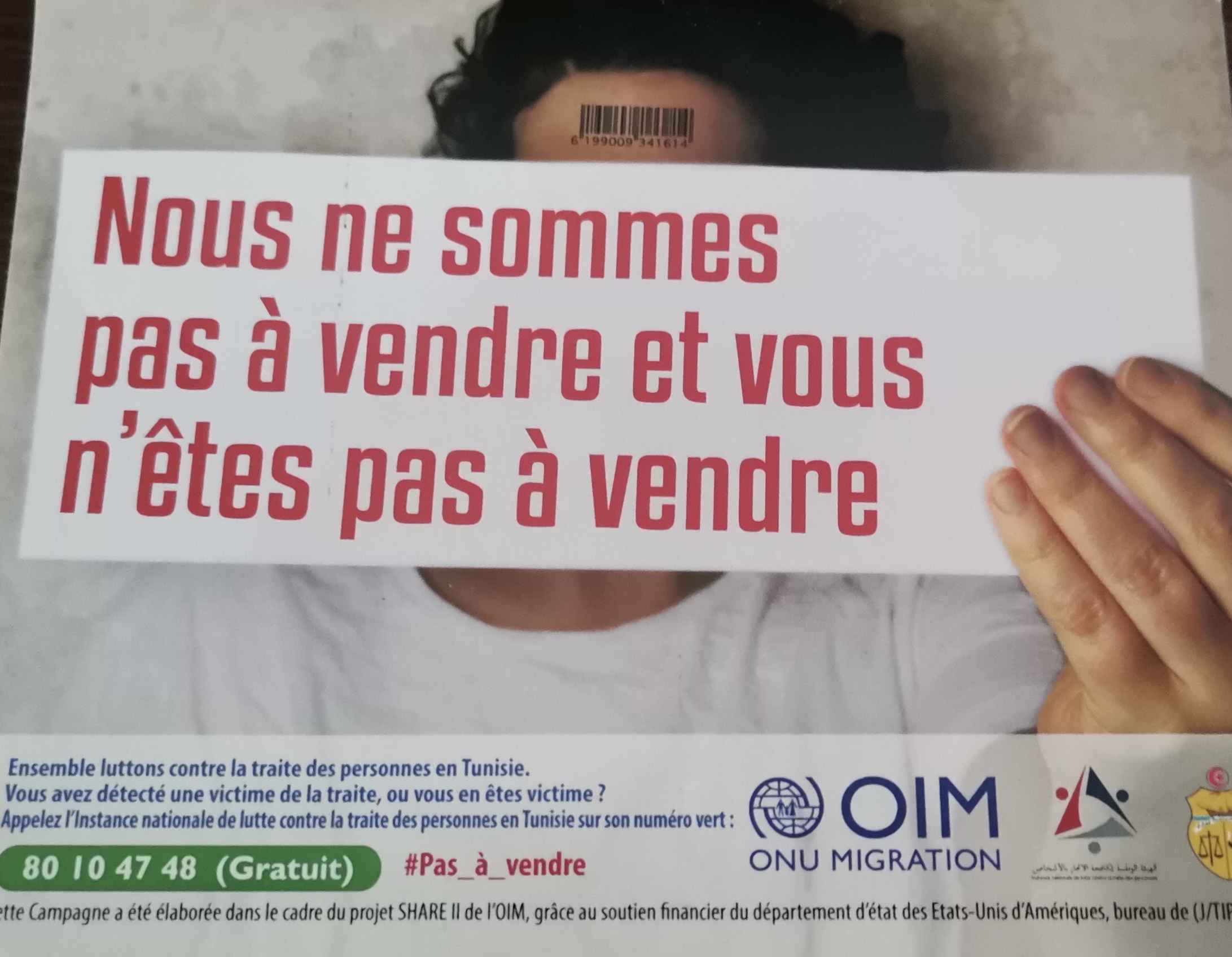

The fact that these migrant women, who are victims of violence, do not file complaints against their aggressors is because the majority of them have irregular administrative status. So they do not complain, despite the Organic Law of 2016 on Preventing and Fighting Human Trafficking, which protects them and penalizes their abusers, and despite the National Authority to Combat Trafficking in Persons set up in 2017 (with admittedly limited resources) to provide them with legal aid and direct them to associations that are friendly to foreigners. Their irregular status increases the fragility and precariousness of their situations while guaranteeing the impunity of the whole chain of individuals who have swindled, abused, exploited, and mistreated these women.

Having entered Tunisia with a three-month tourist visa, they must then obtain a residency permit. But the restrictive nature of the Tunisian national legal framework governing the employment of foreigners and the absence of an asylum law make it almost impossible for migrant women to obtain residency permits because, in order to initiate the permit procedure, they’d need an employment contract and a work permit that are subject to the rules of priority for Tunisian workers. “Foreigners cannot be recruited when there are Tunisians with skills in the specialties in question for recruitment,” stipulates the 1968 law. In the absence of this document, migrants have to pay overstay fines of 20 TD (7 euros) per week. These fines add up and can reach several thousand dinars, sums that migrant men and women generally find impossible to pay—noting that migrant Ivorian men working in the informal construction sector also live in discriminatory conditions and are underpaid compared to Tunisians. And migrants’ trouble in paying overstay penalties was not made any easier even when these penalties were capped at 3,000 TD (900 euros) in 2017. This “undocumented” status not only keeps them in the most informal and subordinate jobs, it also denies them access to the public health system and to the integration of their children in school. Furthermore, it can lead to their expulsion manu militari, not to mention that it prevents them from returning home to see their children for years, thus pushing them towards the “harga,” the clandestine crossing of the Mediterranean. Or towards a distrust of erasure and avoidance strategies that they always have to resume.

Lives hidden from view

Noémie rarely goes out on Sunday’s, her day off, for fear of being checked by the police. Her sociability is at zero: “Why make friends if we can’t see each other? Meet at a café? Or take a walk? Why make friends if the street is a risky, practically forbidden place for us?” she asks. As such, this young woman who arrived in Tunisia a little over a year ago has reduced her contact with others as much as possible—she is discreet, silent, reserved. Invisible.

She doesn’t know about the network of associations that can help her in the event of a serious illness. Nor does she know about the “ganda,” the clandestine cafes-restaurants that are managed and run by Ivorians, where she can eat local dishes and celebrate weddings, engagements, and birthdays away from any Tunisian presence. She hasn’t heard of the community solidarity circles nor the Sunday masses celebrated by sub-Saharan pastors in community spaces. An entire life rendered occult, secret, and underground, in the shadow of a hostile, racist, and misogynistic city that excessively dehumanizes and sexualizes Black African women. Currently working for “good people, who treat me with respect and pay me properly,” assures Noémie, she is working hard to meet the needs of her three children, to whom she sends money through the “Ivorian circuit.” This parallel exchange system costs considerably less than having to send euros through Western Union. Noémie arranges to give the money to Ivorian students in Tunisia, then these students’ parents provide Noémie’s sister with 100 to 200 CFA Francs every month.

But the precariousness persists: last winter, Noémie, whose entire existence is withdrawn from the bustle and noise of the world, unfortunately experienced one of the biggest scares of her life when her neighbors tried to force her out of her home after insulting her and telling her to “get out.”

This form of trafficking is a source of multiple types of interwoven violence. From recruitment in the country of origin until the end of the said “contract,” women are made to suffer economic violence comparable to modern-day slavery.

Deprived of work and evicted from their homes

This happened on the 23rd of February 2023, two days after Tunisian President Kais Saied’s controversial statements during the National Security Council meeting to discuss “urgent measures” to curb the “presence of a large number of illegal migrants from sub-Saharan Africa.” The press release published on the Facebook page of the Presidency of the Republic on February 21 put forward a Tunisian version of the theory of the “great replacement” as part of a “criminal plan that has been in motion since the beginning of this century,” it read. “Some parties have been receiving large sums of money since 2011 to settle irregular immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa in Tunisia” in order to “reduce Tunisia to a purely African character and strip it of its Arab and Islamic affiliation,” it continued.

The day after the presidential remarks, the National Guard announced “a campaign of arrests against Tunisians who host or employ irregular migrants.” In the following days, hundreds—even thousands—of sub-Saharans were deprived of their jobs, evicted from their homes by their landlords, often in the middle of the night and without notice, without even being allowed to take anything with them, let alone recover their deposit. Migrants have become the scapegoats of a deep economic crisis for those who believe in the populist discourse of Kais Saied, and they suffered a wave of violence wherever they happened to be that day: in the bus, the metro, the street…

The will to overcome

Barricaded at home for ten days, Noémie was only able to survive thanks to the solicitude of her boss who gave her unconditional support and regularly brought her supplies. But others were not so lucky: “I was receiving up to 30 calls per day from sub-Saharan migrants in need of help. At the Beity Association, we opened up an emergency unit within our day unit,” recalls Marta Luceno Moreno. “We set up and coordinated an unofficial center for the care of victims of mob justice along with several other feminist and humanitarian associations. There was a need for medical aid, accommodation for those evicted from their homes, and economic aid to pay for housing and bills for those who were unable to go work during this crisis. Our accommodation center filled up very quickly. And the hotels we usually work with to accommodate women victims of violence had been ordered not to open their doors to migrant women.”

The result: the number of irregular entries into the EU through Tunisia reached never-before recorded peaks between March and May 2023: 1,100% compared to the previous year, according to figures from Frontex, the EU agency.

Following the President’s statements, Lydie and Christelle, who became friends after Sunday mass three years ago, did not want to be repatriated by their Embassy in Côte d'Ivoire—as was the case for many of their compatriots. Nor did they want to cross the Mediterranean in small, makeshift, overloaded metal boats, fabricated by smugglers in one day. They chose to stay and resist. The will to overcome the most improbable situations drives them both. Lydie’s goal is to be trained in Tunisia to make French pastries, and Christelle wants to receive training in aesthetics.

“Our life plan is to return to Côte d'Ivoire in two or three years to reunite with our families. Our savings will allow us to open a pastry shop and a beauty salon, respectively. Thanks to the network of Tunisian associations that help migrants out, we’ve found free trainings that we intend to start soon!” the women exclaim together, a wide smile on their faces.

Their eyes shining with a constellation of stars, the relentless struggle to survive life’s most improbable itineraries seems to be their destiny. They have shaped their hardship into an eternally renewing force.