This post is also available in: Français (French)

In order to write your latest book, Islam and Science*, you have delved into and deciphered the texts of many Arab-Muslim thinkers, from the best known to the least known...

It is from the history of science that I was led to deepen my knowledge of religions, particularly Islam. I was not a priori versed in theological questions. What interests me is our relationship to modernity and the question of secularization. I immersed myself in the writings of modern thinkers from Islamic countries, who look at Islam from a scientific perspective without any essentialism.

As I previously told you, I had students at university who had a lot questions. The questions they asked themselves, they passed on to me, starting with this one: is Islam compatible with science? When I did my studies decades earlier, that question did not arise. I was discussing science at that time, and everything encouraged us to discover the whole world. A generation later, some of my students went so far as to reject Einstein's theory. How could they be so different from what I had been at their age? It is true that I had been lucky enough, rare at the time, to be born into a family that pushed me on the scientific path. Knowing the laws of the universe was essential for my father, even if I was to be the only girl to know them among hundreds of boys.

Today, I would love that everyone could freely use their conscience, benefit from knowledge that is universal, and not “Western” as it is sometimes called. I hope to encourage readers to revisit the history of science in the lands of Islam and to discover critical thinking.

In your books, you have detailed how the cultural and scientific heritage has been transmitted over the millennia throughout the world, from scholar to scholar, from philosophy to astronomy, from mathematics to physics.... Then you have analysed how this heritage was transmitted through the Arabic language and through translations into Arabic during the golden age of Islam, and how it accompanied the rise of sciences before falling into decline; finally, how, from the 19th century onwards, it was diverted from its purpose and instrumentalised for the benefit of a “useful” science.

Indeed, after this famous golden age, a long and much less glorious period followed. To take just one example, opposition to the printing press lasted 350 years in Muslim lands. The obscurantism of religious fanatics manifested itself on many occasions and lasted until the 19th century, when Arab reformists, Muslim and Christian intellectuals became aware of the gap that had been created between East and West. They drew lessons from the decline of science in the Arab world and sought a middle way to reconcile attachment to religion with modernity.

In my latest book, Islam and Science, I develop the consequences of this middle way, up to the dead end it has led to. I conclude with the need for a break with the past so that science can return with force to the scene in Islamic countries, and put an end to compromises.

The recent evolution of the countries of the Muslim world, including the most modern ones, such as Turkey or Tunisia, shows that the most retrograde forces of tradition have been maintained, or even imposed at the very moment when they should have lost ground, in the liberation movement that accompanied the independence of formerly colonized countries. This decline is visible in the current reforms of school curricula that result in biology lessons being cut or replaced by religious history lessons. It is also visible in the tensions of Muslim law over the status of women.

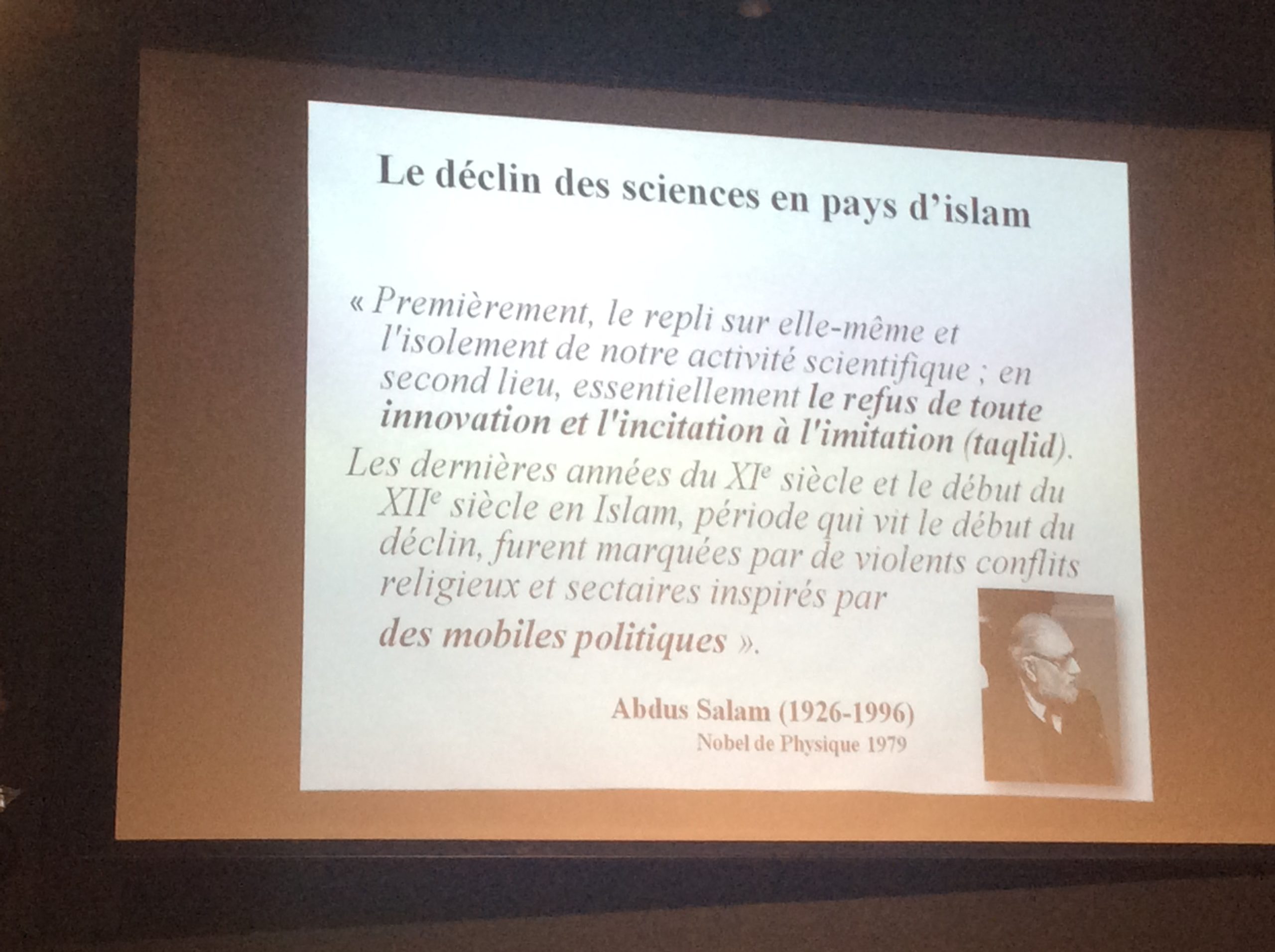

Yet, great contemporary scholars have vigorously rejected the notion of the Islamisation of knowledge. Look at Faztul Rahman, a very pious Indo-Pakistani who invested himself in reviewing the education systems at the time of independence, to open up knowledge to boys and girls alike. Or Abdus Salam, Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979, who worked on the interaction of elementary particles. Being a believer did not prevent him from sharing his research with other scientists from other cultures. When it comes to scientific discovery, religion should not interfere, he stated.

We can no longer accept, after the attempts of Muslim reformists to be trapped in a “sacred” that prohibits reason from questioning the past. No more here in Tunisia than in the United States where religious fundamentalists are gaining ground.

For my part, I work for the autonomy of science, to free it from ideological discourses that are a source of blockage. If science has progressed in the West, it is by detaching itself from the religious sphere. The Muslim nations that have fallen so far behind need to take a leap forward.

We seem to be moving away from feminism, but in reality, everything fits together in your presentation. You make an innovative reading of Islam by opposing it to the totalitarian one, which diverts the Islamic frame of reference from its meaning and claims to have access to all aspects of knowledge. You have also received a prestigious decoration awarded by the Chair of the Arab World Institute (Ima, Paris), which pays tribute to your struggle against Islamist fundamentalism.

Yes, it was in 2019 as part of the Chair of the Arab World Institute that honoured me. The round table was dedicated to Houda Shaarawi, pioneer of the Egyptian and Arab feminist movement. This was an opportunity to develop different themes revolving around the status of women and the conflicting relationship between science and religion.

On this occasion, I recalled how women are gradually becoming more present in mathematical and physical sciences, life and earth sciences. But the situation is not identical across the Muslim world. Tunisia stands out for the remarkable number of women in science. I know of high-level scientific teams of Tunisian female researchers, in cutting-edge fields, in biology, especially biomedical genomics and oncogenetics.

There remains a big black spot in Tunisia for women: when it comes to inheritance, ‘a man is always worth two women…’

The Koran recognizes women as heirs, whether they are mothers, wives, daughters or sisters, but it only grants women half a man’s share - with one exception to this prescription: mothers have a share equal to that of the father. But the daughters inherit half of their brother's share. In the early 1970s Bourguiba had tried to establish equal inheritance between brother and sister. But King Saud Al Faisal of Saudi Arabia warned him that he would break Tunisian-Saudi relations if such a project succeeded, and the project was abandoned.

Inheritance legislation is therefore contrary to the principle of equality and represents a fundamental issue for the defence of women's rights. This is obviously not the only source of inequality. I recall the wage inequality between women and men. This is the case in Tunisia, in the private sector, despite a Tunisian Labour Code specifying, “there should be no discrimination between men and women”. Thus, a female agricultural worker earns up to half as much as a male agricultural worker for the same work. I would add to this observation, the inequality she suffers in terms of inheritance, and even more serious, the fact that some women find themselves dispossessed of the land they cultivate.

At the end of the 1990s, feminist associations such as the Association tunisienne des femmes démocrates (AFTD,Tunisian Association of Democratic Women) and the Association des femmes tunisiennes pour la recherche et le développement (AFTURD, Association of Tunisian Women for Research and Development) brought this issue of equal inheritance back to the forefront of the Tunisian scene. Through their militant commitment, and also within the framework of research involving lawyers, historians and sociologists, they raised awareness at national level. In 1999, the petition launched by the ATFD to demand the abolition of inheritance inequality collected hundreds of signatures. Given the resistance and blockages still present, this fight for inheritance equality continues to this day.

Recently, in Tunis, you once again addressed the subject of inequality during a conference of academics on the theme Women, bodies and religion...

This fight for equality, which remains unfinished, shows the difficulty of changing Muslim societies on the status of women. Across the world, all fundamentalisms converge on the issue of women as on the theory of evolution. And in Tunisia, recent history shows us that the status of women can be threatened when conservative movements are in a position of strength. This was the case after the 2011 elections, when the new constitution was being drafted. We strongly rejected the idea of “complementarity” between the sexes.

We fought for a civil, democratic society project where freedom of expression exists. This fight must be pursued with energy and unequivocally. No ambiguity can be tolerated with respect to the word: Freedom.

What are your concerns… and hopes?

The signs of regression are lurking everywhere in the world. And perhaps we do not imagine that they can be generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI) that will increasingly constitute the world of the future.

Indeed, AI is designed by human beings who are not necessarily free from all prejudice, from all beliefs, or from all stereotypes. It is not an autonomous intelligence, and it is not neutral. As female researchers point out, it reflects the values of its creators. Those who design it will consciously or unconsciously project their imagination in their creation, in the development of algorithms. And what they design is going to reflect their culture. We must therefore question the neutrality and objectivity of artificial intelligence systems.

Artificial Intelligence systems, a contemporary tool that will develop further, must not be allowed to reproduce prejudices that harm the emancipation of women. I believe it is very important to implement a large-scale counter-power to big data, which are not neutral and can be the new tools of discrimination of all kinds. Building a powerful network of action implies that we are very vigilant against all “hidden” biases, voluntarily or “involuntary”, preventing change and progress towards equality between women and men.