This post is also available in: Français (French)

With bright eyes and a welcoming smile that illuminates her face framed by a soft hijab, Takoua arrives breathlessly but on time, in a Rome turned into the usual chaotic quagmire by the pouring rain. "Not an easy city, full of contradictions, but I feel like it’s home. After all, it has welcomed me and raised me as a second mother since my arrival in Italy at the age of eight, she tells."

Born in Tunisia in 1991, she spent her early childhood in Douz, a small southern village, between the oasis of her grandparents, boundless desert and starry nights full of silence and magic.

"I was living with my mother and five brothers because my father, a teacher and human rights activist, had fled shortly after my birth, wanted by the Ben Ali regime."

Supported by a close network of relatives, for years the family resisted heavy threats and continuous police raids in search of that man, first an exile in Sudan and then a political refugee in Italy. In the graphic novel La rivoluzione dei gelsomini (The Jasmine Revolution, Becco Giallo, 2018) Takoua recomposes the pieces of family memory in the larger picture of the dark years under the Tunisian dictatorship.

"I have a bond with all my works, but I have a special relationship with this one," she explains. "It took me three years to create it and it was perhaps the only book I made more for myself than for others. I didn't know my history and I needed to understand who I really was. My parents have told me a lot of things and I’ve found photos, letters, books, videos and newspapers of the time in the archives, collecting testimonies from relatives and friends on facts that had been censored until then. It was very difficult to choose what to write and what not to: I wanted to bear witness to those events while respecting the privacy of the people directly involved."

Powerful female figures

From the pages of this book with a fresh and original style, emerge powerful female figures capable of rebelling with determination against the abuses, censorship and atrocious tortures of an increasingly corrupt and brutal system. Repressed for being activists or persecuted because they are close to the dissidents, women have been the great protagonists of an invisible and silent revolution, but they rarely are included as a part of the great narrative of history. Takoua wants to tell about them, starting from her mother, “a simple housewife of bourgeois extraction" who with sweetness and courage has always defended her freedom and dignity, and that of her children. Then there are the loving paternal grandmother and the young aunt, a brilliant student supporter of the university unions, who despite wearing the veil, banned since 1981, now has multiple degrees and runs a thriving business.

"They were fundamental references of my childhood and together with the other thousands of women who opposed the regime they contributed decisively to its collapse, carrying the seeds of metamorphosis and change", she adds.

After arriving in Italy for family reunification, little Takoua finally meets her father after years of painful distance. "The impact was traumatic: we didn't even have a photograph of him because the police had confiscated everything. I would never have imagined him being white with green eyes, and not dark like me and mum!"

The first year of school is particularly hard for her, but she manages to overcome her shyness by transforming papers and pencils into incredible integration tools. "I only knew the Arabic alphabet and drawing was the only means of communication with my classmates and teachers: I used to draw a toilet to ask to go to the bathroom and I was immediately understood!"

After a short period in a small town near Rome, with neighbors “as caring as relatives in Douz”, in 2001 the family lands in the chaotic metropolitan suburbs. At the age of just 10 Takoua began volunteering at the Centocelle mosque and participated in the first demonstrations for human rights together with her parents, who have always continued doing activism. "I was leading a double life: in the world I was discovering interesting stories that I was telling in my first comics, kept well hidden in a drawer, while at school I was having a hard time in integrating and I was considered a hopeless pupil", she recalls.

Animation film

Takoua grows up watching Japanese cartoons, particularly those of Studio Ghibli, founded by Isao Takata and Hayao Miyazaki, which will greatly inspire her future work. "I was struggling, however, to identify myself with the Disney heroines, apart from Mulan, perhaps because she was not white or a princess but a warrior, obviously different from the others, she adds smiling."

After graduating in animation film at the Nemo Academy of Digital Arts in Florence, she studies journalism in Rome and dedicates herself to graphic journalism before even knowing what it is: “I discovered that it was a real genre thanks to the very famous Palestine by Joe Sacco”, she says. "I was fascinated by the possibility of using comics to raise awareness of all age groups on such delicate issues, but unfortunately it is a very male-dominated ambient: it is still thought that a female author should deal only with female issues or romantic stories, as if political and social commitments do not interest us!"

Yet, human rights have always been at the center of Takoua's projects, as in Un’altra via per la Cambogia (Another way to Cambodia, 2020), born from a collaboration with the Italian NGO WeWorld that denounces the circuits of labor exploitation, prostitution and slavery in which thousands of migrants end up in their attempt to cross the border.

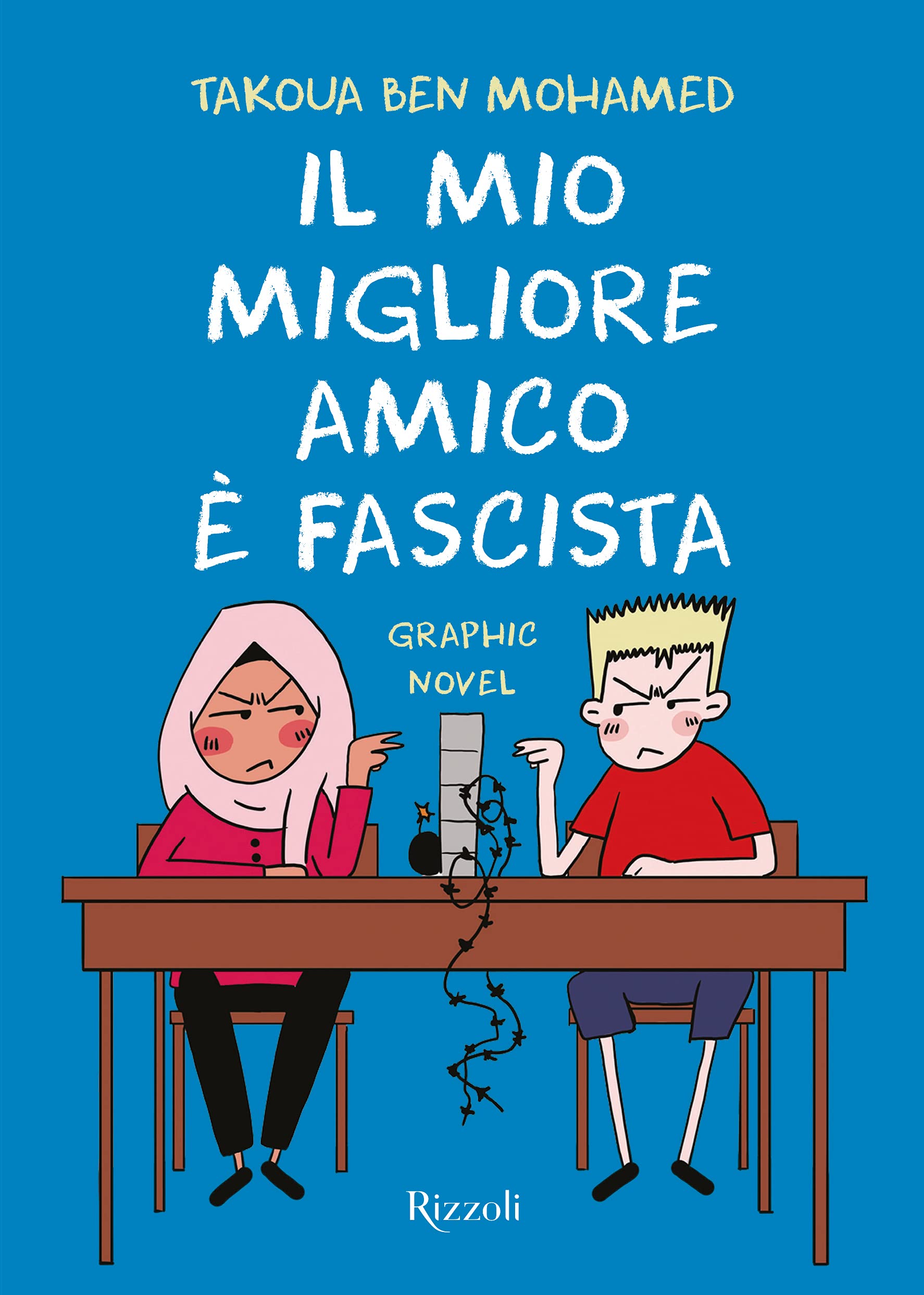

Her latest book, Il mio migliore amico è fascista (My best friend is a fascist, Rizzoli, 2021), tells of the turbulent love and hate relationship with her desk mate in class during her teens, amidst prejudices and cultural stereotypes in the aftermath of September 11th.

"I chose to wear the veil as a reaction, even though I was only 12 years old", she recalls. "My parents and my sisters, who started wearing it when they grew up, advised me against it, fearing it would hinder the integration course by exposing me to offenses difficult to manage at that age. For me it represents an important symbol of freedom and self-determination, despite it being often misunderstood and exploited: my secondary school math teacher considered it a sign of unacceptable submission and she tried in every way to dissuade me. Still today I have to continually explain this choice, although it is very spiritual, intimate and personal for me, and some feminists often argue in debates on the freedom of Arab women that the hijab limits my freedom. I also consider myself a feminist, although I do not identify with any current, and I reply by saying that for me wearing it really means not allowing anyone to influence my behavior! Of course, in some countries its meaning is distorted by a sexist legislature that denies women's rights, as in Afghanistan. But this has nothing to do with religion but with politics and its dangerous authoritarian drifts."

The search of identity

In Sotto il velo (Under the veil, Becco Giallo, 2016), Takoua describes episodes of ordinary discrimination with intelligent irony, with considerations on style and amused replies to the “absurd” questions she receives, underlining the country's deep-rooted Islamophobic tendencies.

The search for identity is like a red thread that interconnects all her works in a constant attempt to answer the emblematic question: “who am I?”

For some she is a “migrant writer”, for others a cartoonist of the “second generation”, but she does not recognize herself in any label and prefers to avoid banal simplifications. “For whites I'm black and for blacks I’m white. In Italy I am the Tunisian, in Tunisia the Italian… I am everything and nothing”, she comments, quoting the texts of Cheb Khaled, pioneer of the Algerian raï genre, who uses the word ghorba to describe the woeful condition of those who leave their country without ever feeling completely at home in the country where they arrive.

"It's a strange suspension that doesn't let you feel rooted anywhere", she adds.

After five years of exhausting wait, Takoua finally obtained Italian citizenship in September: “a long and very tiring path, hindered above all by the economic factor: the prefecture was not giving a positive opinion about me and was continuing to monitor my income. But the acquisition of citizenship should be a right for everyone, not a privilege reserved for those who can afford it! My passports represent a possible integration between two of my many identities.”