This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

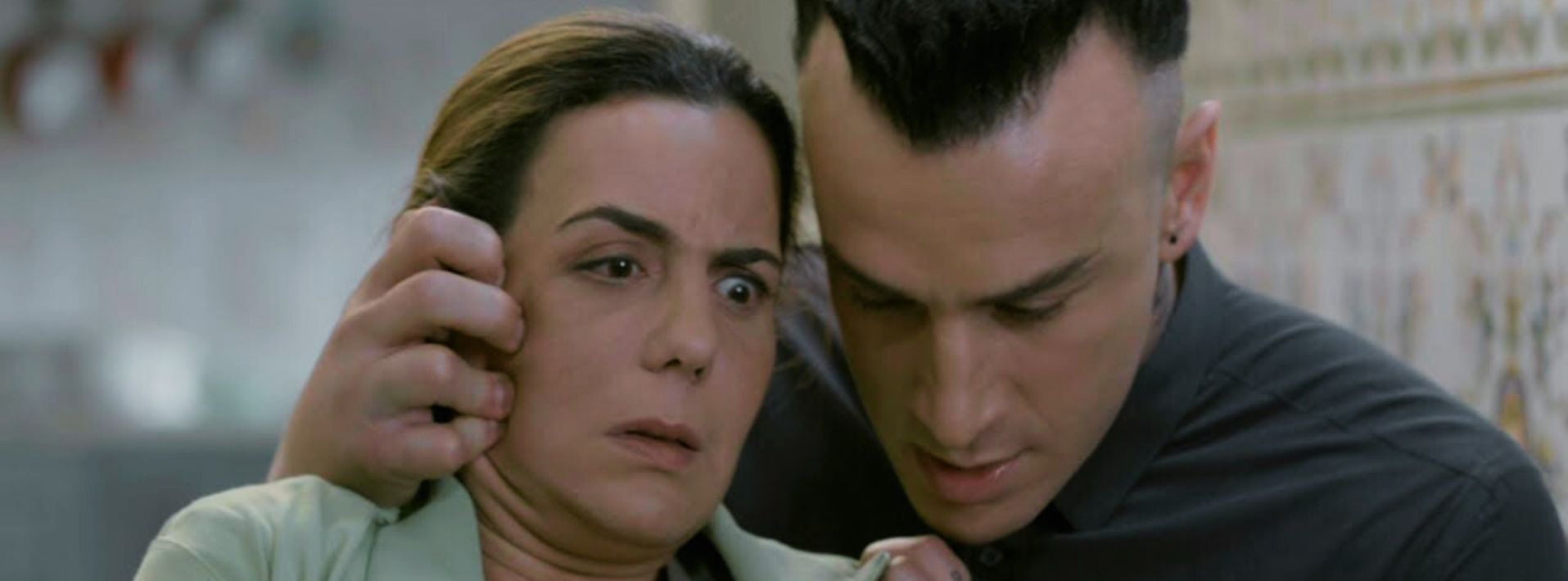

“Bitch,” “dirty” (in the figurative sense of tainted honor), “diabolical,” “viper,” “old idiot,” “donkey,” “moron,” “stupid,” “idiot,” “I’ll make you regret the day you were born,” “shut up, or I’ll disfigure you,” “I’ll kill you if I have to”…

This deluge of insults, stream of invective, and threat of physical attack is what female characters in Ramadan series in 2015 had to deal with. They were reported in a study carried out by the Independent High Authority for Audiovisual Communication (HAICA), the Tunisian body for media regulation—which now no longer exists—in collaboration with the Belgian Superior Audiovisual Council.

This deluge of insults, stream of invective, and threat of physical attack is what female characters in Ramadan series in 2015 had to deal with. They were reported in a study carried out by the Independent High Authority for Audiovisual Communication (HAICA), the Tunisian body for media regulation—which now no longer exists—in collaboration with the Belgian Superior Audiovisual Council.

The study, published in 2017 and entitled “Place and image of women in audiovisual media,” analyzes a corpus of five soap operas broadcast between June 18 and July 17, 2015, namely, Awled Moufida (Moufida’s Sons) and Hkayet Tounsia (Tunisian Stories) on El Hiwar TV, Laylet Echchak (The Night of Doubt) on Attassia TV, Errisque (The Risk) on Hannibal TV, and Naouret Elhwa (Flower of the Breeze) on TV Nationale.

Samira Hammami, coordinator of the study who was also head of the HAICA monitoring body, revealed in a press conference on December 15, 2017, “We counted 225 insults over nearly 69 hours of fiction—so 3.26 insults per hour. The morality and virtue of women are the primary drivers of this violence which insinuates itself into 54% of the offensive comments. The second target of violence is women’s mental faculties, taking up 25% of the insults, underestimating women’s capacity to reason and reflect.”

Curiously, out of these five shows that were examined, three were written by… women! And they also include offensive language addressed to women, albeit slightly less frequently than in the scripts written by men. The study found that production teams are dominated by men in key and high-tech positions: 100% of sound engineers are men, and 80% of producers and editors are men.

Furthermore, the study demonstrated major stereotyping of women’s work, to the extent that 48.85% of scenes show women taking care of their personal affairs in their workplace—not carrying out any tasks having to do with their actual profession. There are also scenes in which the jobs of assistant and secretary are exclusively given to female protagonists.

During the public presentation of the study, Hammami further stated, “The image of women on screen is out of step with social reality. These biased representations of women negatively impact any desire for change and social progress.”