This post is also available in: Français (French)

In the world of cinema where plastic dolls meet the father of the atomic bomb, we are witnessing a collision of ideas and expectations that reflect how polarized society is.

Two films, one social duality

If the names “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” don’t mean anything to you, congratulations, you’ve managed to escape the invasion of pink and media hype of the last few months—and, evidently, the slew of controversy that has ignited the web.

The first film in the running, Barbie, created a real media shock with its wave of pink. In the idyllic world of Barbieland, Barbie dolls occupy all key positions while their male counterparts, the Kens, are relegated to secondary roles. This inversion of traditional roles has aroused the indignation of some critics who see the movie as promoting radical feminism or even a form of anti-male propaganda. The film was even banned from certain cinemas in countries such as Kuwait, Algeria, and recently Cameroon for “attacking morality.”

In a parallel universe, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer immerses us in the story of Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist considered to be the “father of the atomic bomb.” Adopting a non-linear approach, the movie goes back and forth between three key periods in the scientist’s life, highlighting the pivotal role he played in the Manhattan Project and the crucial decisions he had to make. But it doesn’t take long to notice that something in the story doesn’t add up. A few clicks on Google are enough to understand that Nolan, famous for his labyrinthine scripts, seems to have created one more maze, where women are relegated to the background and even erased from history. This is the case with Chien-Shiung Wu, a major scientist of the Manhattan Project who participated in research on the atomic bomb but who doesn’t appear once in Oppenheimer—an ominous reminder that some stories are always hidden in the shadows of great male achievement.

While Barbie has raised ironic concerns about the future of the dominant male in society, Oppenheimer reminds us, in its exclusion of pioneering female scientists, that we are still a long way off. While a movie about a pink doll was pulled from some theaters for “attacking morality,” a biopic about a scientist has unwittingly underlined the need not to overlook the erasure of women from history.

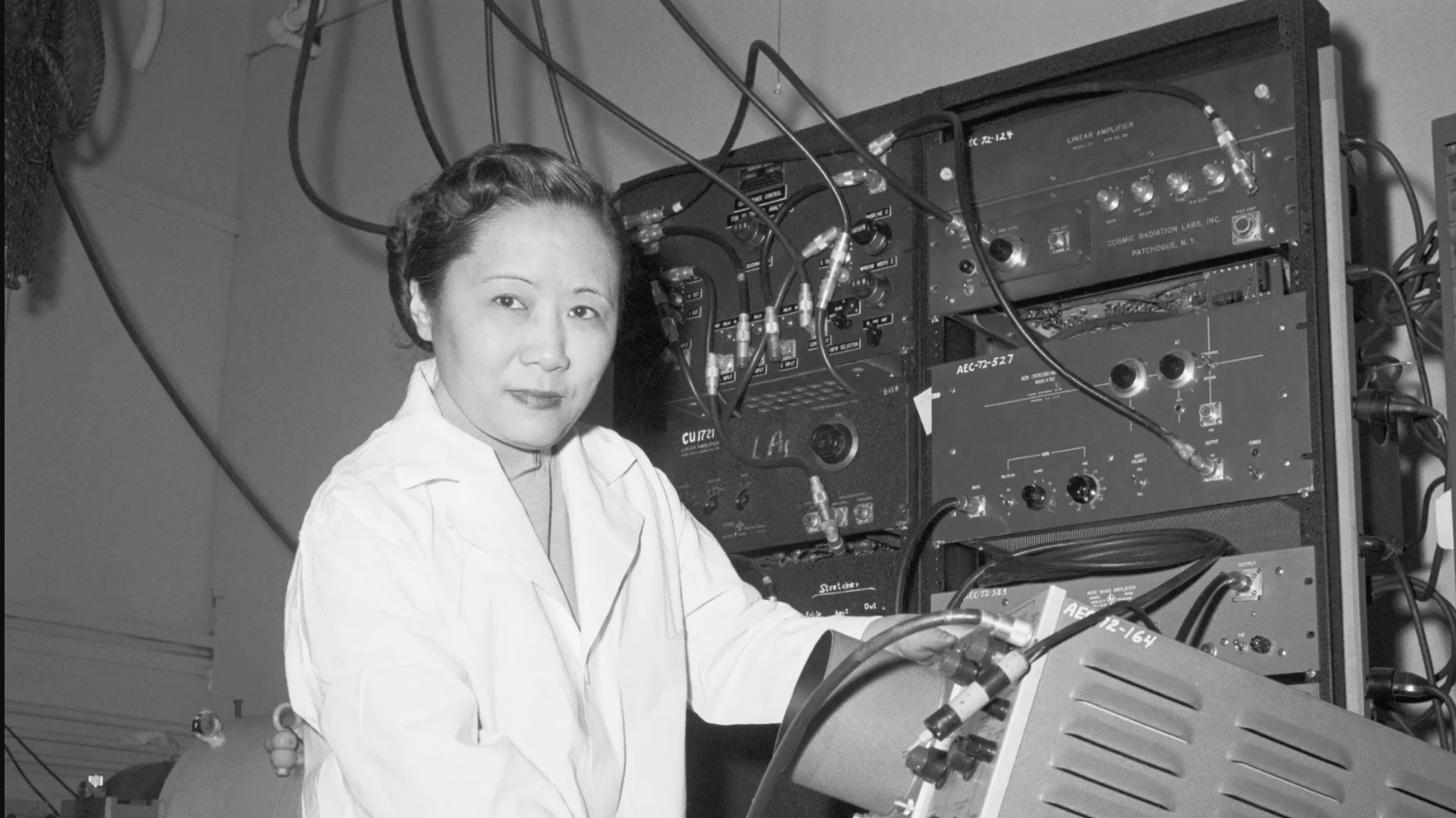

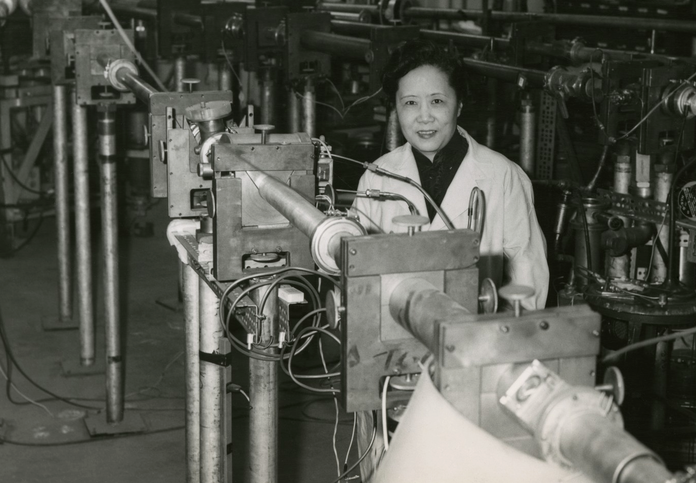

Chien-Shiung Wu: Forgotten contributions

As Barbie and Oppenheimer vie for center stage, the presence of Chien-Shiung Wu looms behind the scenes. The “First Lady of Physics” deserves to have her story be told.

Chien-Shiung Wu was born on May 31, 1912 in Shanghai and died on February 16, 1997 in New York. She remains a brilliant figure in nuclear physics and women’s emancipation. This Chinese-American physicist left an indelible mark on the scientific field, breaking gender barriers and helping shape the foundations of modern nuclear research.

Coming from a progressive family that encouraged the education of girls, Wu quickly distinguished herself by her intellectual brilliance and thirst for knowledge. Despite the cultural and social challenges of the time, she persevered in her academic journey and established herself as a gifted physics student.

Her departure to the United States to continue her studies marked the beginning of a career that would propel her to the top of the scientific community. In 1942, she joined the team of the Manhattan Project, an ultra-secret undertaking that would lead to the creation of the first atomic bomb. Wu made a significant contribution to the development of uranium enrichment processes by gaseous diffusion, a crucial advance for the success of this titanic undertaking.

And yet this was only the beginning of her impact on science. Working with physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang, she was instrumental to the experimental demonstration of non-conservation of parity in weak interactions, challenging a fundamental pillar of physics at the time. Despite this major contribution, the Nobel Prize was awarded to her two male colleagues, highlighting the challenges that women scientists faced in a world still largely dominated by men.

Wu continued to shine throughout her career, winning the first-ever Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978, which recognized her scientific excellence and the profound impact she had on the discipline. She also paved the way for other women by becoming the first female president of the American Physical Society in 1975.

Chien-Shiung Wu’s legacy is not limited to her outstanding scientific achievements. Her courage and determination to confront gender and racist barriers paved the way for future generations of female scientists. She defied gender norms and left her mark as the “First Lady of Physics,” a nickname that honors her status as a pioneer and her indelible contribution to the advancement of science and equality.

Though she passed away in 1997, the legacy of Chien-Shiung Wu, the “Chinese Marie Curie,” lives on in the field of nuclear physics and beyond. Her book Beta Decay, published in 1965, is still a standard reference for nuclear physicists. Her journey illustrates the power of determination, perseverance, and passion for knowledge. Chien-Shiung Wu remains an inspiring role model for anyone looking to push boundaries and leave their mark on the world.