This post is also available in: Français (French)

From the Middle Ages, a collective practice of musical therapy stemming from the syncretism between paganism and peasant civilisation spread in southern Puglia. Known as “tarantism”, in the local dialect, the phenomenon was called pizzica pizzica referring to the sting of the poisonous spider, the tarantula, and the convulsive rhythm of the healing rituals.

In this land "crushed by the sun and solitude, where man walks on mastic trees and clay and where every stone cracks and erodes for centuries"[1], magic and religion were intimately linked and life flowed slowly, marked by the rhythm of the seasons and patronal feasts that guaranteed abundance and fertility. Every summer, the spider awakened from its hibernation and stung those who worked in the fields to harvest tobacco, grapes and wheat. The animal was assigned with specific chromatic and musical preferences and character inclinations that influenced the one who, after the bite, was possessed by it.

From the first symptoms, weakness, anxiety, depression, nausea, hysterical crisis, loss of sight and hearing, the macàra (sorceress) made the diagnosis and relatives hired the musicians for the healing ritual that lasted a few days.

In an outdoor or indoor space, various elements recalling the first bite were placed. These included branches of vines and fruit trees, ears of wheat, a basin of water to cool off, swords as a symbol of the fight against the spider, and mirrors. There were also aromatic plants to stimulate the sense of smell and fabrics of the favorite colors of the tarantula, which died of exhaustion during the dance.

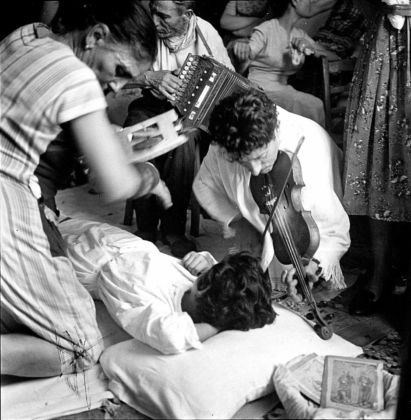

Music was the central element of the therapeutic ritual: sometimes slow and dramatic, sometimes rhythmic and continuous until becoming hypnotic, it was systematically composed of an accordion, a violin, a tambourine and a guitar.

Dressed in white, the person started by crawling on her back, arching, beating her heels and imitating the spider weaving its web. She then got up to step on it and, lastly, ran around the room with a handkerchief in her hand performing more erotic movements.

An extract from the documentary “La taranta”, produced in 1961 by Gianfranco Mingozzi in collaboration with Ernesto De Martino and Diego Carpitella. In recent decades, many musical groups, dance courses, theatrical performances, novels and films have been inspired by tarantism.

Every summer, symptoms reappeared with the end of the agricultural year, when fears about the still uncertain outcome of the harvests and the settlement of debts instilled in souls dark omens and ancestral fears stemming from trauma and unresolved conflicts.

Although scientists have long considered it a foolish superstition of illiterate peasants, tarantism has actually interesting anthropological, psychological and social dimensions. Transcultural psychiatry places it between possession rituals halfway between illness and cultural and religious practice. In a study, we read that “From a psychopathological point of view, […] the subject experiences a dissociative state in which she manifests behaviors very evocative of sexual intercourse. The practice of exorcism itself is full of erotic symbology. In general, not only dramatic situations of survival and psychological distress, especially female, but also, more specifically, traumatic events of a sexual nature can contribute to the epigenesis of the phenomenon.”

The most affected women were precisely those that were at a particularly critical moment in their lives, such as puberty, a denied or unhappy marriage, or widowhood. Oppressed by a patriarchal and authoritarian society, through catharsis they could finally vent their privations and sufferings with the support of the community.

The anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, author of a fundamental study on tarantism[2], links the phenomenon to cults of Dionysus and to the practices of the Corybantes among the Greeks as well as to the possession rituals of the Muslim world.

For Georges Lapassade[3], who has studied with the phenomenon for a long time in the context of his research on trance, “[...] it would be the latest expression of the Asian cult of the" Mother Goddess”. Another reference is also made to the myth of Arachne, the beautiful maiden who dared to challenge Athena in the art of weaving and was transformed into a spider as a punishment.

The percussionist Colucci[4] recalls that the tambourine, a central instrument in the ritual, was traditionally exclusively played by women and that it represents the female sex: a sacred cavity that is struck in cults related to fertility and lunar cycles.

Many healers used their saliva as an antidote. Transmission took place through the "open" female line, that is, not tied to the members belonging to the same patrilineal family.

As from the 18th century, in order to limit this phenomenon that was beyond ecclesiastical control, the Catholic Church imposed the figure of Saint Paul[5] as protector of tarantulas and tarantata. However, the women initially reacted to this constraint by tearing off clothes, desecrating altars and heightening the erotic component in the presence of the clergy.

Since the 1960s, with the mechanization of agriculture and the use of pesticides and herbicides, Salento has lost its rural origin: tarantism has become a source of shame for many and disappeared in a few decades. "In June 1981 only three tarantate made the pilgrimage in the midst of a crowd of tourists, journalists and cameramen," reports Lapassade[6].

However, the decline of the phenomenon is undoubtedly also linked to the change in the socio-cultural status of women, today less oppressed than in the past, although patriarchal conditioning is still deeply rooted in the country, especially in the South.