This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

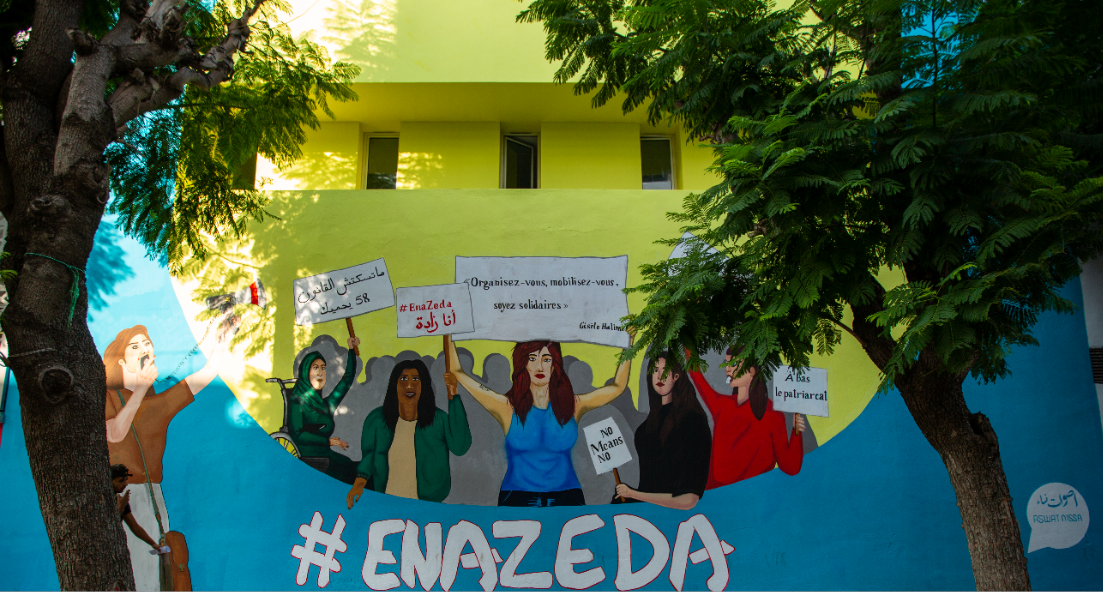

On the Avenue de Paris, in downtown Tunis, the walls of the French Institute of Tunis (IFT) stretch for several meters. This is where a brightly coloured naive-looking fresco signed by the young collective of Tunisian artists called “Blech Issm” (No Name) has been displayed since October 2020. The fresco features women in motion and angry, holding banners, waving their slogans and their rights to dignity and respect for their bodies. The painting recalls scenes observed during the national protest against violence against women organised by the “Association tunisienne des femmes democrats” (ATFD, Tunisian Association of Democratic Women), in collaboration with several other feminist NGOs on 30 November, 2019.

We read “Organisez-vous. Mobilisez-vois. Soyez solidaires” (Organize, mobilize, unite.) at the centre of the fresco. The quote of Gisèle Halimi, a French lawyer of Tunisian origin who passed away on 28 July, 2020 and to whom the Association “Asswat Nissa” (Voice of Women) wished to pay tribute.

“Gisèle Halimi’s appeal is so in line with the Ena Zeda campaign” state both Sarra Ben Said, Executive Director of “Asswat Nissa,” and Sonia Ben Miled, communications officer of the association.

The fresco, which accompanied a multimedia exhibition of testimonies in the form of silhouettes and poignant texts, will remain imprinted on the facade of the Institute until the wind, the rain and the sun decide otherwise and sweep away the artists’ work throughout the seasons.

Through this street art form, the “Asswat Nissa Association” actually wanted to celebrate a year of sexual violence denunciation in continuity with the wave of protest that began in mid-October 2011.

The mobilization in question took place following a news item that horrified the Tunisian web: the captured images of a newly elected deputy at the end of the electoral campaign of 2019, pants down, masturbating outside a high school in his car while gazing at a 19-year-old girl. And so the #EnaZeda hashtag was born. The hashtag is a literal translation of #MeToo, a movement that became internationally renowned as of October 2017 when a New York Times article detailed accusations of sexual harassment against Harvey Weinstein, studio boss, powerful producer and distributor of Hollywood films, through the revelations of actresses, victims of this powerful man, creating a snowball effect soon after this first publication.

" My story is not that unique. I am not a black sheep "

A community of more than 45,000 members

The EnaZeda hashtag soon became a plea against sexual violence. Having followed the case of the young girl exposed to the harmful lust of the deputy, “Asswat Nissa” decided to launch a Facebook group called EnaZeda to support the high school student but also all victims of sexual abuse by offering legal guidance to those who wish to file a complaint.

Designed by the visual artist Wadi Mhiri, the multimedia exhibition launched by the “Asswat Nissa” in October tells stories lived in fear, the pain and guilt of rape, stories of harassment and sexual violence through the voices of children, adolescents and young women and men. Made up of whispers and a background sound with dreamlike and almost imperceptible intonations, the sound environment that inhabits the space provokes a disturbing feeling of “already heard” words.

“At the end of his mission, the graphic designer who created the arrangement of texts carried by the silhouettes of victims told me: “Ena Zeda”! Half-heartedly, he told me about his trauma that is still present following a “bump on the road” suffered in his early youth. This is to tell you to what extent our patriarchal society is dominated by the phenomenon of harassment,” explains Wadi Mhiri.

Having followed the case of the young girl exposed to the harmful lust of the deputy, “Asswat Nissa” decided to launch a Facebook group called EnaZeda to support the high school student, but also all victims of sexual abuse.

As from the first months of the launch of the EnaZeda group, a community of 45,000 members formed. More than 1000 testimonies were scandalous, shattering and at times even unbearable to read. They show how dangerous the family is for children and how crimes of incest and paedophilia concern all social classes.

“Harassers do not make laws!”

Azza, 20 years old: “I was 11 years old. My uncle had just divorced. He started visiting us regularly at the time. I felt that his words and his attitude towards me had changed. One morning, I was washing my face. He walked into the bathroom and locked the door. He then started hugging and kissing me, putting his tongue in my mouth. I struggled, pushed him away and quickly ran to tell everything to my mother. She didn’t believe me and forbade me to say a word about it to anyone to avoid a “scandal”.

Emna, 18 years old: “One day, I took a taxi. The driver started telling me that I was pretty and very provocative before grabbing my thighs while I was sitting in the back seat. I asked him to remove his hand. However, till today, I wonder why I didn’t just get out of the car.”

Ridha, 28 years old: “I was a 9-year-old boy when one day, I went to the bookstore to print pictures and documents for a research requested by my teacher. I was so focused on the computer that I didn’t notice that the bookseller had pulled his pants down and came closer to me: “Let’s play a little together”, he told me. I ran away. I had never spoken about this trauma.”

Hana, 20 years old: “As soon as I came out of school, I used to meet my father’s childhood friend. He used to wait for me to accompany home. He said he was afraid for me as bad boys could hurt. One day, he rushed me into an abandoned building and raped me. I wanted to die… Worst of all: I never dared to confide this heavy secret to my father, or to another member of my family because my terrible story continued until adolescence.”

During the months that followed the affair of the deputy, stories were continuously posted on social media networks all day long, and each one was more unbearable than the other. According to “Asswat Nissa”, it is the return of the repressed among young people aged between 18 and 34, an age group that represents the nucleus of the Facebook group and who chanted “harassers do not make laws!” on 13 November 2019, during the inaugural session of the second legislature, where young men and women came to denounce the presence of the deputy accused of sexual harassment among the newcomers to parliament.

It is the return of the repressed among young people aged between 18 and 34 who chanted: “harassers do not make laws!”

A safe place for victims

Sonia Ben Miled, a dynamic “Asswat Nissa” activist who moderates the group according to a predefined charter, stresses the importance of feeling safe, a feeling that must reign in this virtual space of exchange and sometimes of catharsis. “We systematically eliminate ill-intentioned comments targeting victims so that they do not feel judged or denigrated and are not afraid of reprisals; especially since recent figures from UN Women revealed that cyber violence affects 73% of women in the world”.

In recent years, the psychologist and psychotherapist Sondoss Garbouj has specialized in the care of survivors of sexual assault and abuse. A few months ago, she participated in a webinar organized by “Asswat Nissa” and explained the benefits the EnaZeda group offers to victims: disclosure, the removal of guilt, and the possibility of breaking with moral isolation.

“My story is not that unique. I am not a black sheep,” will state the survivors upon reading all other denunciations of old and new traumas, explains Sondoss Garbouj, with a touch of hope. The beginning of deliverance starts to take shape…