This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

By Pascale Sawma - Lebanese journalist and author

History remembers Antarah’s love for his cousin Abla as one of the greatest love stories in classical Arabic poetry. But no one seems to ask whether Abla really loved Antarah. There’s no evidence in history or in literature that suggests she reciprocated his love. What about Omar ibn Abi Rabia, were women really infatuated with him? Was he really handsome? There’s no evidence to prove the legends either. Epics passed on to us were all narrated by men who recounted stories of love and chastity, war, heroism and chivalry.

According to tradition, the storytellers had to be men and they were naturally inclined to retell stories of their own kind. There were hardly any female poets for all we know and tracing their history required a great deal of research and unearthing. If anything, these poetesses were mentioned in small print or in footnotes. Women’s voices were deemed inconsequential and not worthy of much consideration. That’s why students and scholars never learned about them.

We never got to hear what the women thought of the Arab conquests or the ‘chivalrous’ enslavement of women in the wake of every battle, transferred like property from one tribe to another. Did Abla find in Antarah the man of her dreams, or was it all an illusion in his head? Was their love as chaste as he claimed or was it just a made-up lie that he circulated – and later believed in - to protect the girl he loved? Maybe platonic love was the real deal back then. There’s no denying that ancient Arabic poetry, dominantly authored by male poets, centered around sexual repression, unfulfilled romances, and thinly disguised erotica, raising excitement by describing forbidden kisses and threatened encounters. The same repression has been hunting women’s voices and attempting to silence them forever.

In ancient Arabic poetry, women were portrayed as icons, like untouchable deities

or an unfulfilled fantasy…

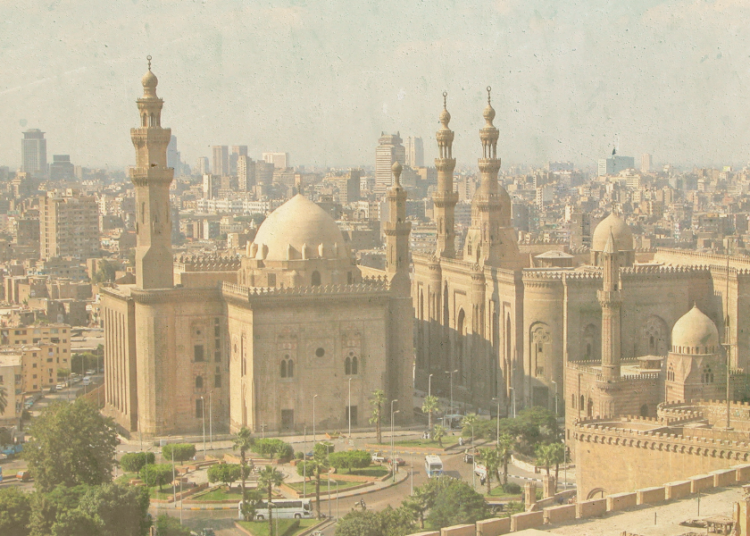

Most of the ancient poems we inherited sing in unison the monotonous tune of masculinity, but its misdeeds were nevertheless hailed in the name of chivalry, lawful reprisal, or what they sometimes call ardent love. These poetic works that have been passed down to generations are presented as the great literary legacy that can never be questioned. When Taha Hussein, one of Egypt's most esteemed writers and intellectuals, attempted to criticize the Jahili poetry, he was tried in court and subjected to death threats. Similarly, orientalists, such as David Samuel Margoliouth, were condemned for saying that what we know about the Jahili poetry was written during the Islamic period and therefore doesn’t accurately represent the religion, society, or economy of Jahili times.

In ancient Arabic poetry, women were portrayed as icons and goddesses. Their beauty was admired in the opening verses, even if love wasn’t the main focus of the poem. Women were like untouchable deities or an unfulfilled fantasy. This is exactly how men still like to perceive women today in a society that’s hooked on its old ailments. Many still see women as inferior creatures that lack the capacity to react or refuse. For them the best woman is the one who remains unsullied and preserves society’s religious and canonical embalmment on her body and mind.

Maysoon, daughter of Bahdal of the Kalbiya tribe, was a poet that no one knew about. All that’s written about her is that she was Mu'awiya’s wife, while few are the literary references that delve into her delicate poems, which are no less than Mu'awiya’s own poetry and possibly even better.

“I will give my cheek to my lover

and my kisses to anyone I choose”

While Arabic poetry served to glorify the heroic Arab conquests (Al Mutanabi wrote: “In the desolate wasteland, beasts kept my solitary company / to the astonishment of the hills and the mountains”), poetry by slave women in captivity, known as Jawari' poetry, was far overlooked. Their writings were daring and teeming with defiance and unrestraint. These women were victims of patriarchy, of fierce battles, and of men whose names, just like Al-Mutanabi’s, were well known to the horses, the night and the desert. The early poetess Dahiya Al-hilaliya wrote in one of her poems: “Dead be my father had I savored anything sweeter than the taste of my lover’s mouth. If I had to choose between his embrace and my own father, fatherless I shall be.”

The daring poetess Wallada bint al-Mustakfi, founder of the main literary salon in Andalusian times, said: “I will give my cheek to my lover and my kisses to anyone I choose.”

On Women’s Day, our journey back in time shows how old a device women’s marginalization is and how it continues to plague our societies till this day. Some found their cure, while others are still probing this tactic in the realms of politics and economy, and in homes behind closed doors - through violence, oppression and restraint – to keep women on the margins. If heard, their voices are nothing more than a cherry on top of a man-made cake or a fight over a questionable quota. When an elite country adopts the gender quota, women are expected to bow down in reverence and appreciate this act of chivalry bestowed on their sex by the great men of their nation.