This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

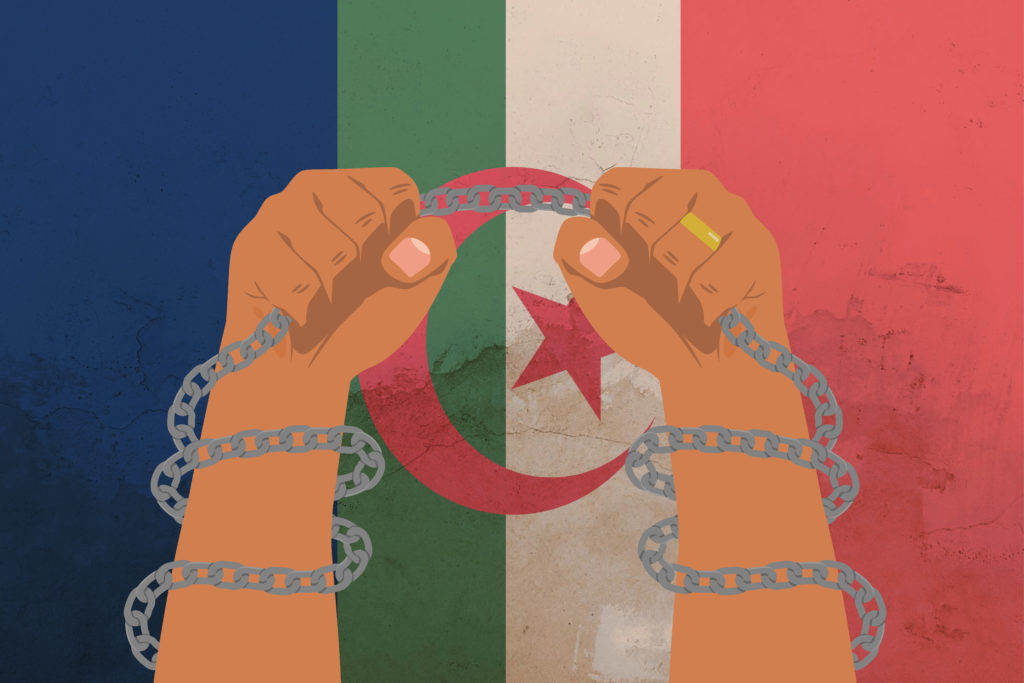

Article 3 of the French Civil Code stipulates that regarding personal status, every person is subject to the law of their country of which they are a national. This is how women in France can still be subject to the Algerian Family Code, the Moroccan Moudawana, and the Egyptian personal status law. National laws that not only enshrine discrimination against women and gender inequality, but also inequality among women according to their nationality of origin.

The wives of French nationals or residents receive a one-year residence permit upon marriage, but they then need to wait at least four years for a definintive permit. They depend entirely on their husbands for every step of the process during this waiting time. Those who enter the country on a tourist visa because the husband cannot or does not want to apply for family reunification also find themselves without access to any rights. The same applies to cases of polygamous “husbands” whose first wife is legitimate and has the right to a residence permit, while the others have irregular status.

All these women are in a legislative blind spot, and this also extends to provisions on victims of violence. Mostly, they do not know the laws of the host country, speak little or no French, are cloistered in the marital home, and their documents are withheld by their spouse. And yet Article 313-12 of the Code of Entry and Residence of Foreigners stipulates that “if the foreign national has been subjected to domestic violence from her/his spouse and the couple’s married life has ceased, the administrative authority (prefecture) does not have the right to withdraw the foreign national’s residence permit and should authorize the permit to be renewed.” In practice, women do not usually file a complaint for fear of being deported of of reprisals from the husband and family.

All these women do not know the laws of the host country, speak little or no French, are cloistered in the marital home, and their documents are withheld by their spouse.

The case of Algerian women

The revised Franco-Algerian bilateral agreement of 1968 keeps Algerian women in France under the yoke of the Algerian Family Code. Serina Badaoui, a lawyer in Lille who offers legal support to migrants, has often come across cases of Algerian women who were dismissed at the prefecture because common law is not applied to them. Even if they are victims of domestic violence or human trafficking, they cannot benefit from the protection of French law.

La Cimade confirms to us that “this is a legal no-man’s land for Algerian women. There is nothing in the bilateral agreement about wives. These women are completely dependent on the discretion of the prefect. But not all prefects want to make these kinds of efforts, as they worry about acting in contradiction with national law.” Recently, the Algerian President was expressing pride at how this agreement has been maintained, warning that repealing it is out of the question. But his remarks included no mention as to the consideration of improving the lot of his country’s female nationals.

The Algerian government has badly taken the incessant demands of French politicians who want to put an end to agreements deemed too favorable to the immigration of Algerians. An assessment that Mimouna Hadjam, of the Africa association, does not agree with in the least. This association has been fighting for an autonomous status for migrant women for years. “We don’t want to be governed by the laws of our countries of origin anymore. We want to be governed by French law. We live here, we work here. Is an Algerian or Moroccan thief judged under Algerian or Moroccan law? Obviously not!”

In 2016, the Africa association and the Femmes Solidaires network launched a campaign to support the proposed bill then presented by Communist MP Marie-George Buffet. In her presentation in July 2015, the MP stated that “it is necessary to enshrine in the law of our Republic the rights allowing the autonomy of migrant women by changing the legislative rules to guarantee them a stable residence permit, autonomous status, and a work permit.”

Despite being rejected by the Senate, these initiators have accomplished a victory: they’ve guaranteed immigrant women’s access to a residence permit in cases of recognized domestic violence. But migrant women in general are still not guaranteed autonomous status. Algerian women in particular remain dependent on their spouse to obtain a residence permit. This dependence triggers dramatic situations of violence, domestic slavery, and even pimping.

“The dream women have of a husband in France quickly transforms into a nightmare. Women find themselves at the service of their in-laws, suffering from the different forms of violence enacted by their husbands who refuse to get their papers processed. Even women who have come through the family reunification program find themselves locked up with no resources and no papers, seeing as the prefecture refuses to issue a residence permit without the spouse present,” explains Mimouna Hadjam, indignant. She reminds us that it now takes four consecutive years, not the two years previously required, for women to obtain a residence permit and put an end to their spouses’ blackmailing.

All associations supporting migrant women are aware of these tragic stories and are trying to save the victims of violent spouses who sometimes even force their wives into prostitution. The legal battles are complex. Maimouna tells us that the law on the protection of women victims of violence is still “blurry” when it comes to complying with the bilateral agreement. In their work, associations try to obtain a protection order for the victim “after a complaint has been successfully processed,” Maimouna specifies, in order to then be able to apply for a residence permit.

Algerian women in particular remain dependent on their spouse to obtain a residence permit. This dependence triggers dramatic situations of violence, domestic slavery, and even pimping.

But there are still more obstacles to overcome. “Access to lawyers is difficult and expensive. A simple appeal can be invoiced up to 2,000 euros. And legal aid doesn’t always work—it takes a really invested lawyer for this mechanism to be effective. The exequatur, essential to the judgments of the first court, is also a complicated step for women. Especially since in recent years it has been increasingly required of these women to hire a lawyer for procedures and steps that used to be completed by simple letters written by the victim herself, or by a social worker.”

Women can challenge the effects of the court’s ruling but not the ruling itself. Divorce pronounced in the country of origin is usually men’s favored process because it’s faster and cheaper. Though it is not contestable, women can still claim alimony in France. Because of the many polygamy cases, some of which have been brought to the level of European courts, Algerian courts now summon the wife living abroad when her spouse submits a request for divorce. A small step forward that does not compensate much for the application of the family law governing the liquidation of assets that the couple may possess in Algeria.

Feminist activists such as Maimouna Hadjam want to make further strides in granting migrant women autonomy on French soil, even in the current political context that is not conducive to a more egalitarian status for these women. They have again approached Communist deputies to submit a bill to this effect.