This post is also available in: Français (French) العربية (Arabic)

I have actually tried to write about this countless times since I was let out of that cold, dark cell, but I never fully went through with it. I was afraid that the narrow room might have missed my tears, my weak voice, and therefore somehow manage to pull me back in. Or that those blue mattresses might have missed the weight of my weary body. Or even that the high ceiling missed my eyes looking up at it, yearning for freedom.

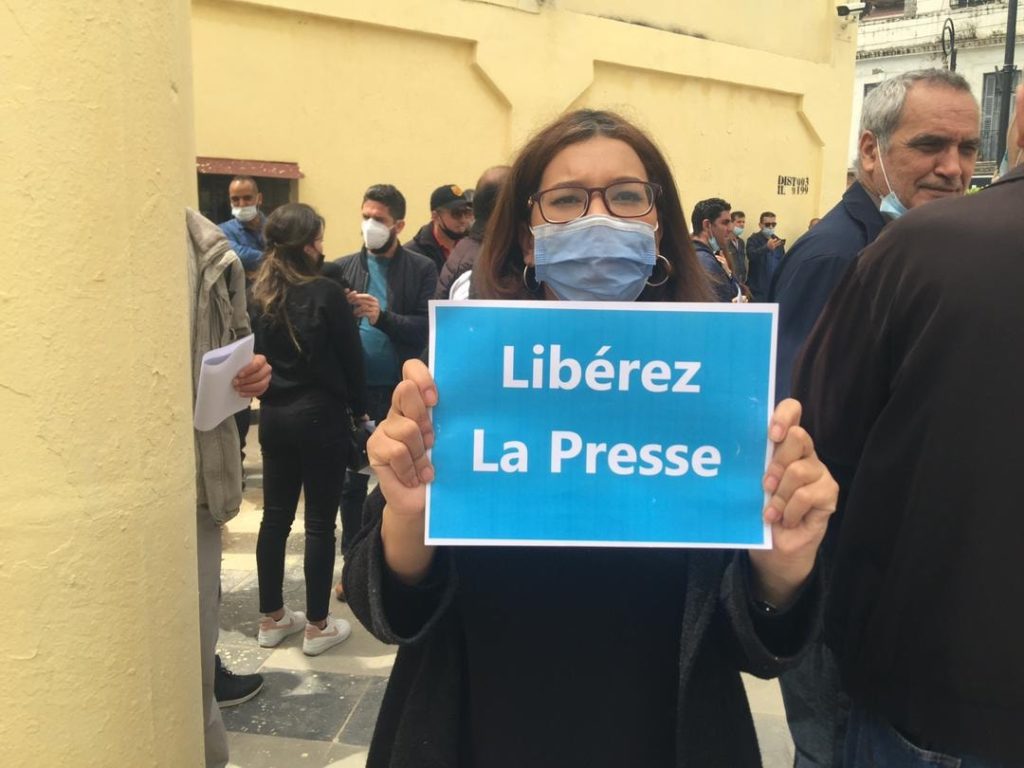

I didn’t write, but not because something inside me was refusing to go back to those days I spent in a cell. In fact, I wrote a lot in my life, took photographs, I talked. But how difficult it is—still—to tell the story of my arrest and detainment, when I don’t know where to start or where to end. When I haven’t even reached the end yet. Yes, the struggle for a free and independent press is an endless one.

I am spending the night in a security facility, facing the headquarters of the first media outlet I worked for

On the second day of Eid al-Fitr, and days after the commemoration of World Press Freedom Day, specifically on the 14th of May, 2021, I was arrested and placed “under supervision” until May 18, 2021.

I had been covering a march by the popular protest movement with a number of other journalists and photographers, and at that point the movement had been going on for three consecutive years. I was arrested and taken to the security facility in Algiers—the capital. I was kept there until about four o’clock, at which point I was transported to another security facility. There, I was able to catch a glimpse of fellow journalists who had also been arrested.

I thought I was going to be allowed to leave the facility after being interrogated, but while my colleagues did leave, I was made to stay and keep waiting. It was getting late, and I was starting to get scared. At around eleven PM, after I was asked questions about myself and why I had been at the march, they told me that I was going to spend the night under supervision. I signed the “minutes” and took advantage of my right to contact a member of my family.

I was breaking down and couldn’t stop sobbing. I had so many questions but was so exhausted that I couldn’t figure any of them out. Then I was taken to a forensic doctor for examinations, and after that I was led to a cell in the heart of the capital, located opposite the headquarters of the first media outlet I worked for after I graduated in 2014. A coincidence if there ever was one!

You’re just a journalist

It might seem strange, but as soon as I walked in there, the first person that came to mind wasn’t my mother, nor any of my siblings or colleagues or friends, but the Minister of Communication at the time: how was he sleeping tonight?

I laid down on one of those mattresses, a white light shining straight into my eye blinding my thoughts even further. I was asking myself a lot of questions, but I settled for one answer before my body surrendered and I fell into a deep sleep: you’re just a journalist.

Solidarity was my support through those days

When I was being held in the cell, the lawyer Zubaida Asoul visited me, then my mother, then my brother. They were my only link to what was going on outside.

I asked the lawyer if what they were telling me in there was true, that my arrest and detention hadn’t caught the attention of any of my colleagues. She answered me, confused: “On the contrary, all of your colleagues are standing in solidarity with you.”

My mother, who visited me on my second day in that place, hugged me as if she were hugging me for the first time. Then she told me that the whole world was talking about me: “Kenza, everyone is talking about what happened to you. All the channels are reporting on it, and our house is full of people I don’t know who have come to comfort me.”

My brother visited me the following day. He hugged me, trying to hide his tears. He looked at me with his red eyes and said: “My sister, the pain inside me is as great as my joy. I am proud of you and what you do. You have widespread solidarity out there.” Indeed, solidarity was my support through those days, hours, minutes, and seconds that I spent waiting to discover what my fate would be.

Will I be taken to prison?

During my detention, I was taken back to the security facility only once, handcuffed, and they asked me for the passcode to access my phone, which they'd confiscated. I refused to give it to them, of course, because Algerian law gives me the right to do that in order to protect my sources as a journalist.

On 18 May 2021, they told me at an early hour that I would be taken to court. I felt such joy, though I was still inside the cell, and I ran to the private stairs to change my clothes and say goodbye to this lifeless place.

How slowly time was passing, despite the proximity of the court. I arrived and had to wait in another cell there, below the seat of the Sidi M’hamed court in Algiers. It was the most difficult day of my life. Was I going to be taken to prison, or would I be able to embrace freedom again?

Fainting in front of the judge

I first appeared before the investigating judge. He asked me questions and I answered them, encouraged by the lawyers accompanying me. I left the courtroom and was taken back to the area below, and after some time, a security agent escorted me back upstairs, where the lawyers informed me that I was to appear before the judge in an immediate trial, by a decision of the investigating judge.

I waited for hours and couldn't stop crying. My body temperature dropped, and I felt dizzy and nauseous, questions racing through my mind about the press, the media, and my fate if I were to be put behind bars.

It was my turn to appear before the judge. I climbed up some winding stairs, the door in front of me was opened, and there were my colleagues, my friends, my family, and a very large crowd of lawyers, male and female. The judge called out to me, but her voice sounded far away, and it kept getting farther and farther until I fainted from extreme fatigue, fear, and other feelings I can’t describe.

After I regained consciousness, the judge asked me if I wanted to continue with the trial that day. I said: “If I accept this trial, will I then go home with my family?” She replied that I had to answer with a yes or no, so I decided to postpone the trial. I was released, and the judge postponed the trial for one week.

“The director of the radio (Radio M) Ihsane El-Kadi did not accept my resignation and told me that I’m a journalist, and that nothing will stop me from practicing this profession”

I tasted freedom again, but the nightmare wasn’t over

I left the court and went back home. I tasted freedom again, but the nightmare wasn’t over. Many charges were brought against me: threatening national unity, incitement to non-armed gathering, unarmed gathering, distributing publications harmful to the national interest, and insulting a statutory body. These accusations were leveled against me for having practiced a profession that I loved, that had been a childhood dream of mine. I love my country and not once have I ever thought of threatening its unity or harming its interest.

During the trial, I was acquitted of the charge of threatening national unity and the gathering charges, and I was given a three-month suspended prison sentence and a fine. During the appeal, the court acquitted me of all the charges.

Nobody will stop me from practicing this profession

After I was released from the cell, it took a long time for me to be able to get back to work. I submitted my resignation from Radio M because I was psychologically exhausted. But the director of the radio Ihsane El-Kadi did not accept my resignation and told me that I’m a journalist, and that nothing and nobody will stop me from practicing this profession.

Thanks to the massive solidarity that I received from public opinion and the immense support of my colleagues in this profession of troubles, not to mention the support from my family, I did return to presenting news and radio broadcasts, and I resumed writing and media coverage. I continued practicing this profession which had been my childhood dream, now fulfilled. The issue of my arrest and detention made me even more determined to continue informing public opinion.

Ideas and free speech cannot be imprisoned

Today, as we mark World Press Freedom Day 2023, the director of Radio M has been behind bars since 24 December 2022. He was given a sentence of five years, three of which he must serve in jail. I lost my job after the headquarters was sealed, but I am still convinced that even though the body may be imprisoned and the premises sealed, ideas and free speech cannot be imprisoned, no matter how frequent and sharpened the attempts.